Augustine of Hippo, also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings influenced the development of Western philosophy and Western Christianity, and he is viewed as one of the most important Church Fathers of the Latin Church in the Patristic Period. His many important works include The City of God, On Christian Doctrine, and Confessions.

Jihad is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God's guidance, such as struggle against one's evil inclinations, proselytizing, or efforts toward the moral betterment of the Muslim community (Ummah), though it is most frequently associated with war. In classical Islamic law (sharia), the term refers to armed struggle against unbelievers, while modernist Islamic scholars generally equate military jihad with defensive warfare. In Sufi circles, spiritual and moral jihad has been traditionally emphasized under the name of greater jihad. The term has gained additional attention in recent decades through its use by various insurgent Islamic extremist, militant Islamist, and terrorist individuals and organizations whose ideology is based on the Islamic notion of jihad.

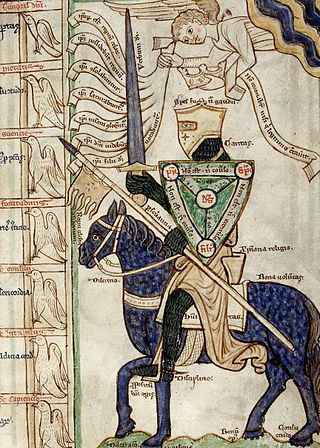

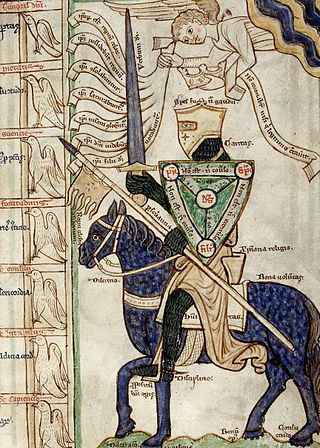

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the Middle Ages. Technological, cultural, and social advancements had forced a severe transformation in the character of warfare from antiquity, changing military tactics and the role of cavalry and artillery. In terms of fortification, the Middle Ages saw the emergence of the castle in Europe, which then spread to the Holy Land.

Pelagianism is a Christian theological position that holds that the original sin did not taint human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve human perfection. Pelagius, an ascetic and philosopher from the British Isles, taught that God could not command believers to do the impossible, and therefore it must be possible to satisfy all divine commandments. He also taught that it was unjust to punish one person for the sins of another; therefore, infants are born blameless. Pelagius accepted no excuse for sinful behaviour and taught that all Christians, regardless of their station in life, should live unimpeachable, sinless lives.

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy, meaning 'vindication of God' in Greek, is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when omnipotence, omnibenevolence, and omniscience are all simultaneously ascribed to God. Unlike a defence, which merely tries to demonstrate that the coexistence of God and evil is logically possible, a theodicy additionally provides a framework wherein God's existence is considered plausible. The German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz coined the term "theodicy" in 1710 in his work Théodicée, though numerous attempts to resolve to the problem of evil had previously been proposed. The British philosopher John Hick traced the history of moral theodicy in his 1966 work Evil and the God of Love, identifying three major traditions:

- the Plotinian theodicy, named after Plotinus

- the Augustinian theodicy, which Hick based on the writings of Augustine of Hippo

- the Irenaean theodicy, which Hick developed, based on the thinking of St. Irenaeus

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of various chivalric orders; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed by chivalrous social codes. The ideals of chivalry were popularized in medieval literature, particularly the literary cycles known as the Matter of France, relating to the legendary companions of Charlemagne and his men-at-arms, the paladins, and the Matter of Britain, informed by Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, written in the 1130s, which popularized the legend of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table. All of these were taken as historically accurate until the beginnings of modern scholarship in the 19th century.

The just war theory is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. It has been studied by military leaders, theologians, ethicists and policymakers. The criteria are split into two groups: jus ad bellum and jus in bello. The first group of criteria concerns the morality of going to war, and the second group of criteria concerns the moral conduct within war. There have been calls for the inclusion of a third category of just war theory dealing with the morality of post-war settlement and reconstruction. The just war theory postulates the belief that war, while it is terrible but less so with the right conduct, is not always the worst option. Important responsibilities, undesirable outcomes, or preventable atrocities may justify war.

The Crusading movement was a framework of ideologies and institutions that described, regulated, and promoted the Crusades. Members of the Church defined the movement in legal and theological terms based on the concepts of holy war and pilgrimage. Theologically, the movement merged ideas of Old Testament wars that were instigated and assisted by God with New Testament ideas of forming personal relationships with Christ. The concept of crusading as holy war was based on the ancient idea of just war, in which an authority initiates the war, there is just cause, and the war is waged with pureness of intention. Adherents saw Crusades as special pilgrimages—a physical and spiritual journey under the authority and protection of the Church. Pilgrimage and crusade were penitent acts and they considered participants part of Christ's army. While this was only metaphorical before the First Crusade, the concept transferred from the clergy to the wider world. Crusaders attached crosses of cloth to their outfits, marking them as followers and devotees of Christ, responding to the biblical passage in Luke 9:23 which instructed them to carry one's cross and follow Christ. Anyone could be involved and the church considered those who died campaigning martyrs. After the First Crusade the movement became an important part of late-medieval western culture, impacting politics, the economy and society.

Semi-Pelagianism is a Christian theological and soteriological school of thought about the role of free will in salvation. In semipelagian thought, a distinction is made between the beginning of faith and the increase of faith. Semi-Pelagian thought teaches that the latter half – growing in faith – is the work of God, while the beginning of faith is an act of free will, with grace supervening only later. Semi-Pelagianism in its original form was developed as a compromise between Pelagianism and the teaching of Church Fathers such as Saint Augustine. Adherents to Pelagianism hold that people are born untainted by sin and do not need salvation unless they choose to sin, a belief which had been dismissed as heresy. In contrast, Augustine taught that people cannot come to God without the grace of God. Like pelagianism, semipelegianism was labeled heresy by the Western Church at the Second Council of Orange in 529.

The history of Christian thought has included concepts of both inclusivity and exclusivity from its beginnings, that have been understood and applied differently in different ages, and have led to practices of both persecution and toleration. Early Christian thought established Christian identity, defined heresy, separated itself from polytheism and Judaism and invented supersessionism. In the centuries after Christianity became the official religion of Rome, some scholars say Christianity became a persecuting religion. Others say the change to Christian leadership did not cause a persecution of pagans, and that what little violence occurred was primarily directed at non-orthodox Christians.

The historiography of the Crusades is the study of history-writing and the written history, especially as an academic discipline, regarding the military expeditions initially undertaken by European Christians in the 11th, 12th, or 13th centuries to the Holy Land. This scope was later this extended to include other campaigns initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Roman Catholic Church. The subject has involved competing and evolving interpretations since the capture of Jerusalem in 1099 until the present day. The religious idealism, use of martial force and pragmatic compromises made by those involved in crusading were controversial, both at the time and subsequently. Crusading was integral to Western European culture, with the ideas that shaped behaviour in the Late Middle Ages retaining currency beyond the 15th century in attitude rather than action.

Christians have had diverse attitudes towards violence and nonviolence over time. Both currently and historically, there have been four attitudes towards violence and war and four resulting practices of them within Christianity: non-resistance, Christian pacifism, just war, and preventive war. In the Roman Empire, the early church adopted a nonviolent stance when it came to war because the imitation of Jesus's sacrificial life was preferable to it. The concept of "just war", the belief that limited uses of war were acceptable, originated in the writings of earlier non-Christian Roman and Greek thinkers such as Cicero and Plato. Later, this theory was adopted by Christian thinkers such as St Augustine, who like other Christians, borrowed much of the just war concept from Roman law and the works of Roman writers like Cicero. Even though "Just War" concept was widely accepted early on, warfare was not regarded as a virtuous activity and expressing concern for the salvation of those who killed enemies in battle, regardless of the cause for which they fought, was common. Concepts such as "Holy war", whereby fighting itself might be considered a penitential and spiritually meritorious act, did not emerge before the 11th century.

The Augustinian theodicy, named for the 4th- and 5th-century theologian and philosopher Augustine of Hippo, is a type of Christian theodicy that developed in response to the evidential problem of evil. As such, it attempts to explain the probability of an omnipotent (all-powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-loving) God amid evidence of evil in the world. A number of variations of this kind of theodicy have been proposed throughout history; their similarities were first described by the 20th-century philosopher John Hick, who classified them as "Augustinian". They typically assert that God is perfectly (ideally) good, that he created the world out of nothing, and that evil is the result of humanity's original sin. The entry of evil into the world is generally explained as consequence of original sin and its continued presence due to humans' misuse of free will and concupiscence. God's goodness and benevolence, according to the Augustinian theodicy, remain perfect and without responsibility for evil or suffering.

Pseudo-Augustine is the name given by scholars to the authors, collectively, of works falsely attributed to Augustine of Hippo. Augustine himself in his Retractiones lists many of his works, while his disciple Possidius tried to provide a complete list in his Indiculus. Despite this check, false attributions to Augustine abound.

The miles Christianus or miles Christi is a Christian allegory based on New Testament military metaphors, especially the Armor of God metaphor of military equipment standing for Christian virtues and on certain passages of the Old Testament from the Latin Vulgate. The plural of Latin miles (soldier) is milites or the collective militia.

Eleonore Stump is an American philosopher who serves as the Robert J. Henle Professor of Philosophy at Saint Louis University, where she has taught since 1992.

Knightly Piety refers to a specific strand of Christian belief espoused by knights during the Middle Ages. The term comes from Ritterfrömmigkeit, coined by Adolf Waas in his book Geschichte der Kreuzzüge. Many scholars debate the importance of knightly piety, however it is apparent as an important part of the chivalric ethos based on its appearance within the Geoffroi de Charny's "Book of Chivalry" as well as much of the popular literature of the time.

Augustinianism is the philosophical and theological system of Augustine of Hippo and its subsequent development by other thinkers, notably Boethius, Anselm of Canterbury and Bonaventure. Among Augustine's most important works are The City of God, De doctrina Christiana, and Confessions.

Herbert Edward John Cowdrey (1926–2009), known as H. E. J. Cowdrey or John Cowdrey, was an English historian of the Middle Ages and an Anglican priest. He was elected priest of St Edmund Hall, University of Oxford, in 1956. He resigned the chaplaincy in 1976, but continued to teach medieval history there until 1994, when he retired and was elected emeritus fellow. He was also a Fellow of the British Academy. A leading expert on the Gregorian reforms, his most important work is the monograph Pope Gregory VII, 1073–1085, considered a masterpiece "unlikely to be surpassed".

Augustinian Calvinism is a term used to emphasize the origin of John Calvin's theology within Augustine of Hippo's theology over a thousand years earlier. By his own admission, John Calvin's theology was deeply influenced by Augustine of Hippo, the fourth-century church father. Twentieth-century Reformed theologian B. B. Warfield said, "The system of doctrine taught by Calvin is just the Augustinianism common to the whole body of the Reformers." Paul Helm, a well-known Reformed theologian, used the term "Augustinian Calvinism" for his view in the article "The Augustinian-Calvinist View" in Divine Foreknowledge: Four Views.