Susa was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about 250 km (160 mi) east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital of Elam and the winter capital of the Achaemenid Empire, and remained a strategic centre during the Parthian and Sasanian periods.

Elam was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of southern Iraq. The modern name Elam stems from the Sumerian transliteration elam(a), along with the later Akkadian elamtu, and the Elamite haltamti. Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East. In classical literature, Elam was also known as Susiana, a name derived from its capital Susa.

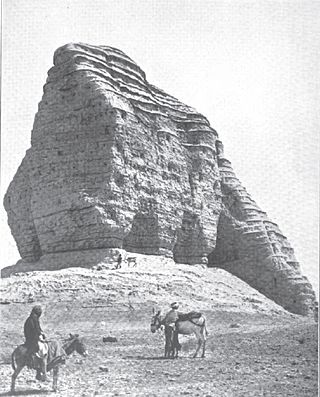

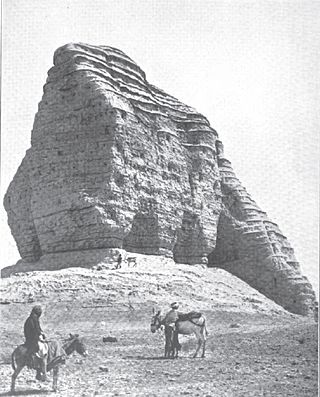

Chogha Zanbil is an ancient Elamite complex in the Khuzestan province of Iran. It is one of the few existing ziggurats outside Mesopotamia. It lies approximately 30 km (19 mi) southeast of Susa and 80 km (50 mi) north of Ahvaz. The construction date of the city is unclear due to uncertainty in the chronology of the reign of Untash-Napirisha but is clearly sometime in the 14th or 13th century BC. The conventionally assumed date is 1250 BC. The city is currently believed to have been destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian ruler Assurbanipal in about 645 BC, along with the Elamite capital of Susa though some researchers place the end of occupation in the late 12th century BC. The ziggurat is considered to be the best preserved example of the stepped pyramidal monument by UNESCO. In 1979, Chogha Zanbil became the first Iranian site to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Humban was an Elamite god. He is already attested in the earliest sources preserving information about Elamite religion, but seemingly only grew in importance in the neo-Elamite period, in which many kings had theophoric names invoking him. He was connected with the concept of kitin, or divine protection.

Inshushinak was the tutelary god of the city of Susa in Elam. His name has a Sumerian etymology, and can be translated as "lord of Susa". He was associated with kingship, and as a result appears in the names and epithets of multiple Elamite rulers. In Susa he was the main god of the local pantheon, though his status in other parts of Elam might have been different. He was also connected with justice and the underworld. His iconography is uncertain, though it is possible snakes were his symbolic animals. Two Mesopotamian deities incorporated into Elamite tradition, Lagamal and Ishmekarab, were regarded as his assistants. He was chiefly worshiped in Susa, where multiple temples dedicated to him existed. Attestations from other Elamite cities are less common. He is also attested in Mesopotamian sources, where he could be recognized as an underworld deity or as an equivalent of Ninurta. He plays a role in the so-called Susa Funerary Texts, which despite being found in Susa were written in Akkadian and might contain instructions for the dead arriving in the underworld.

The Proto-Elamite period, also known as Susa III, is a chronological era in the ancient history of the area of Elam, dating from c. 3100 BC to 2700 BC. In archaeological terms this corresponds to the late Banesh period. Proto-Elamite sites are recognized as the oldest civilization in Iran. The Proto-Elamite script is an Early Bronze Age writing system briefly in use before the introduction of Elamite cuneiform.

The Proto-Elamite script is an early Bronze Age writing system briefly in use before the introduction of Elamite cuneiform.

Ezatollah Negahban was an Iranian archaeologist known as the father of Iranian modern archaeology.

Tepe Sialk is a large ancient archeological site in a suburb of the city of Kashan, Isfahan Province, in central Iran, close to Fin Garden. The culture that inhabited this area has been linked to the Zayandeh River Culture.

Kiririsha was a major goddess worshiped in Elam.

Tapeh Yahya is an archaeological site in Kermān Province, Iran, some 220 kilometres (140 mi) south of Kerman city, 90 kilometres (56 mi) south of Baft city and 90 km south-west of Jiroft. The easternmost occupation of the Proto-Elamite culture was found there.

Kurigalzu I, usually inscribed ku-ri-gal-zu but also sometimes with the m or d determinative, the 17th king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty that ruled over Babylon, was responsible for one of the most extensive and widespread building programs for which evidence has survived in Babylonia. The autobiography of Kurigalzu is one of the inscriptions which record that he was the son of Kadašman-Ḫarbe. Galzu, whose possible native pronunciation was gal-du or gal-šu, was the name by which the Kassites called themselves and Kurigalzu may mean Shepherd of the Kassites.

Kadašman-Ḫarbe I, inscribed in cuneiform contemporarily as Ka-da-áš-ma-an-Ḫar-be and meaning “he believes in Ḫarbe ,” was the 16th King of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty of Babylon, and the kingdom contemporarily known as Kar-Duniaš, during the late 15th to early 14th century BC. It is now considered possible that he was the contemporary of Tepti Ahar, King of Elam, as preserved in a tablet found at Haft Tepe in Iran. This is dated to the “year when the king expelled Kadašman-KUR.GAL,” thought by some historians to represent him although this identification has been contested. If this name is correctly assigned to him, it would imply previous occupation of, or suzerainty over, Elam.

The Stele of Meli-Šipak is an ancient Mesopotamian fragment of the bottom part of a large rectangular stone edifice engraved with reliefs and the remains of Akkadian and Elamite inscriptions. It was taken as spoil of war by Elamite king Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I during his invasion of Babylonia which deposed Kassite king Zababa-šuma-iddina. It was one of the objects found at Susa between 1900 and 1904 by the French excavation team under Jacques de Morgan that seems to have formed part of an ancient Museum of trophies, or ex-voto offerings to the deity Inšušinak, in a courtyard adjacent to the main temple.

Tepti-ahar was the king of Elam at the end of 15th or the beginning of 14th century BCE. He was apparently the last king of the Kidinuid dynasty, who returned to the use of the old title “King of Susa and Anzan”. Tepti-Ahar built a new capital of Kanbak. The excavated archive shows the diplomatic exchange with Babylonia, possibly even dynastic marriages. A tablet found at Haft Tepe (HT38) is dated to the “year when the king expelled Kadašman-KUR.GAL”. The tablet has a seal of Tepti-Ahar, King of Susa. KUR.GAL could be read either as “Harbe”or “Enlil”, p. 202-204.

Manzat (Manzât), also spelled Mazzi'at, Manzi'at and Mazzêt, sometimes known by the Sumerian name Tiranna (dTIR.AN.NA) was a Mesopotamian and Elamite goddess representing the rainbow. She was also believed to be responsible for the prosperity of cities.

Lagamal or Lagamar was a Mesopotamian deity associated chiefly with Dilbat. A female form of Lagamal was worshiped in Terqa on the Euphrates in Upper Mesopotamia. The male Lagamal was also at some point introduced to the pantheon of Susa in Elam.

Ishmekarab (Išmekarab) or Ishnikarab (Išnikarab) was a Mesopotamian deity of justice. The name is commonly translated from Akkadian as "he heard the prayer," but Ishmekarab's gender is uncertain and opinions of researchers on whether the deity was male or female vary.

Tepe Sofalin is an ancient Near Eastern archeological site on the Tehran Plain south of the Alborz Mountains on the north-central plateau of Iran about 10 kilometers east of the modern city of Varamin and 35 kilometers southeast of the modern city of Tehran. It lies in the Tehran Province of Iran. Sofalin means pottery shards in Persian. It was occupied from the Late Chalcolithic period until the Early Bronze period, during the Proto-Elamite Period, and again in the Iron III period. The site of Tape Shoghali is adjacent and the site of Tepe Hissar is only a few kilometers away.