Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to people of the opposite sex; it "also refers to a person's sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions." Someone who is heterosexual is commonly referred to as straight.

A lesbian is a homosexual woman or girl. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with female homosexuality or same-sex attraction. The concept of "lesbian" to differentiate women with a shared sexual orientation evolved in the 20th century. Throughout history, women have not had the same freedom or independence as men to pursue homosexual relationships, but neither have they met the same harsh punishment as gay men in some societies. Instead, lesbian relationships have often been regarded as harmless, unless a participant attempts to assert privileges traditionally enjoyed by men. As a result, little in history was documented to give an accurate description of how female homosexuality was expressed. When early sexologists in the late 19th century began to categorize and describe homosexual behavior, hampered by a lack of knowledge about homosexuality or women's sexuality, they distinguished lesbians as women who did not adhere to female gender roles. They classified them as mentally ill—a designation which has been reversed since the late 20th century in the global scientific community.

Sexual orientation is an enduring personal pattern of romantic attraction or sexual attraction to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. Patterns are generally categorized under heterosexuality, homosexuality, and bisexuality, while asexuality is sometimes identified as the fourth category.

Bi-curious is a term for a person, usually someone who is a self-identified heterosexual, who is curious or open about engaging in sexual activity with a person whose sex differs from that of their usual sexual partners. The term is sometimes used to describe a broad continuum of sexual orientation between heterosexuality and bisexuality. Such continuums include mostly heterosexual or mostly homosexual, but these can be self-identified without identifying as bisexual. The terms heteroflexible and homoflexible are mainly applied to bi-curious people, though some authors distinguish heteroflexibility and homoflexibility as lacking the "wish to experiment with sexuality" implied by the bi-curious label. It is important when discussing this continuum to conclude that bisexuality is distinct from heterosexuality and homosexuality rather than simply an extension of said sexualities like the labels heteroflexibility and homoflexibility would imply, due to the prominent erasure and assimilation of bisexuality into other identity groups. To sum it up, the difference between bisexual and bicurious is that bisexual people know that they are sexually attracted to both genders based on personal experience. Bicurious people are still maneuvering their way through their sexuality.

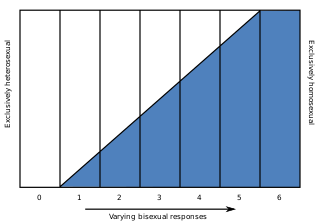

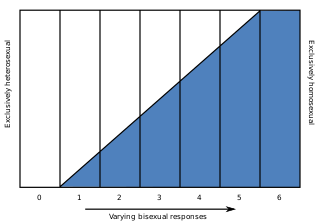

The Kinsey scale, also called the Heterosexual–Homosexual Rating Scale, is used in research to describe a person's sexual orientation based on one's experience or response at a given time. The scale typically ranges from 0, meaning exclusively heterosexual, to a 6, meaning exclusively homosexual. In both the male and female volumes of the Kinsey Reports, an additional grade, listed as "X", indicated "no socio-sexual contacts or reactions" (asexuality). The reports were first published in Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) by Alfred Kinsey, Wardell Pomeroy, and others, and were also prominent in the complementary work Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953).

Biphobia is aversion toward bisexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being bisexual. Similarly to homophobia, it refers to hatred and prejudice specifically against those identified or perceived as being in the bisexual community. It can take the form of denial that bisexuality is a genuine sexual orientation, or of negative stereotypes about people who are bisexual. Other forms of biphobia include bisexual erasure.

The field of psychology has extensively studied homosexuality as a human sexual orientation. The American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality in the DSM-I in 1952, but that classification came under scrutiny in research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. That research and subsequent studies consistently failed to produce any empirical or scientific basis for regarding homosexuality as anything other than a natural and normal sexual orientation that is a healthy and positive expression of human sexuality. As a result of this scientific research, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the DSM-II in 1973. Upon a thorough review of the scientific data, the American Psychological Association followed in 1975 and also called on all mental health professionals to take the lead in "removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated" with homosexuality. In 1993, the National Association of Social Workers adopted the same position as the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association, in recognition of scientific evidence. The World Health Organization, which listed homosexuality in the ICD-9 in 1977, removed homosexuality from the ICD-10 which was endorsed by the 43rd World Health Assembly on 17 May 1990.

Sexual identity refers to one's self-perception in terms of romantic or sexual attraction towards others, though not mutually exclusive, and can be different to romantic identity. Sexual identity may also refer to sexual orientation identity, which is when people identify or dis-identify with a sexual orientation or choose not to identify with a sexual orientation. Sexual identity and sexual behavior are closely related to sexual orientation, but they are distinguished, with identity referring to an individual's conception of themselves, behavior referring to actual sexual acts performed by the individual, and sexual orientation referring to romantic or sexual attractions toward persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, to both sexes or more than one gender, or to no one.

Obtaining precise numbers on the demographics of sexual orientation is difficult for a variety of reasons, including the nature of the research questions. Most of the studies on sexual orientation rely on self-reported data, which may pose challenges to researchers because of the subject matter's sensitivity. The studies tend to pose two sets of questions. One set examines self-report data of same-sex sexual experiences and attractions, while the other set examines self-report data of personal identification as homosexual or bisexual. Overall, fewer research subjects identify as homosexual or bisexual than report having had sexual experiences or attraction to a person of the same sex. Survey type, questions and survey setting may affect the respondents' answers.

Monosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction to members of one sex or gender only. A monosexual person may identify as heterosexual or homosexual. In discussions of sexual orientation, the term is chiefly used in contrast to asexuality and plurisexuality. It is sometimes considered derogatory or offensive by the people to whom it is applied, particularly gay men and lesbians. In blogs about sexuality, some have argued that the term "monosexuality" inaccurately claims that homosexuals and heterosexuals have the same privilege. However, some have used the term "monosexual privilege", arguing that biphobia is different from homophobia.

Sexual attraction to transgender people has been the subject of scientific study and social commentary. Psychologists have researched sexual attraction toward trans women, trans men, cross dressers, non-binary people, and a combination of these. Publications in the field of transgender studies have investigated the attraction transgender individuals can feel for each other. The people who feel this attraction to transgender people name their attraction in different ways.

Bisexual erasure, also called bisexual invisibility, is the tendency to ignore, remove, falsify, or re-explain evidence of bisexuality in history, academia, the news media, and other primary sources.

Sexuality in transgender individuals encompasses all the issues of sexuality of other groups, including establishing a sexual identity, learning to deal with one's sexual needs, and finding a partner, but may be complicated by issues of gender dysphoria, side effects of surgery, physiological and emotional effects of hormone replacement therapy, psychological aspects of expressing sexuality after medical transition, or social aspects of expressing their gender.

Situational sexual behavior is a type of sexual behavior which differs from that which the person normally exhibits, due to a social environment that in some way permits, encourages, or compels the behavior in question. This can include situations where a person's preferred sexual behavior may not be possible, so rather than refraining from sexual activity completely, they may engage in substitute sexual behaviors.

The questioning of one's sexual orientation, sexual identity, gender, or all three is a process of exploration by people who may be unsure, still exploring, or concerned about applying a social label to themselves for various reasons. The letter "Q" is sometimes added to the end of the acronym LGBT ; the "Q" can refer to either queer or questioning.

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, to more than one gender, or to both people of the same gender and different genders. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, which is also known as pansexuality.

Sexual fluidity is one or more changes in sexuality or sexual identity. Sexual orientation is stable and unchanging for the vast majority of people, but some research indicates that some people may experience change in their sexual orientation, and this is slightly more likely for women than for men. There is no scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed through psychotherapy. Sexual identity can change throughout an individual's life, and does not have to align with biological sex, sexual behavior, or actual sexual orientation.

The demographics of sexual orientation and gender identity in the United States have been studied in the social sciences in recent decades. A 2022 Gallup poll concluded that 7.1% of adult Americans identified as LGBT. A different survey in 2016, from the Williams Institute, estimated that 0.6% of U.S. adults identify as transgender. As of 2022, estimates for the total percentage of U.S. adults that are transgender or nonbinary range from 0.5% to 1.6%. Additionally, a Pew Research survey from 2022 found that approximately 5% of young adults in the U.S. say their gender is different from their sex assigned at birth.

Compulsory heterosexuality, often shortened to comphet, is the theory that heterosexuality is assumed and enforced upon people by a patriarchal and heteronormative society. The term was popularized by Adrienne Rich in her 1980 essay titled "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence". According to Rich, social science and literature perpetuate the societal belief that women in every culture are believed to have an innate preference for romantic and sexual relationships with men. She argues that women's sexuality towards men is not always natural but is societally ingrained and scripted into women. Comphet creates the belief that society is overwhelmingly heterosexual and delegitimizes queer identities. As a result, it perpetuates homophobia and legal inequity for the LGBTQ+ community.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBT topics.