Related Research Articles

Genomic imprinting is an epigenetic phenomenon that causes genes to be expressed or not, depending on whether they are inherited from the mother or the father. Genes can also be partially imprinted. Partial imprinting occurs when alleles from both parents are differently expressed rather than complete expression and complete suppression of one parent's allele. Forms of genomic imprinting have been demonstrated in fungi, plants and animals. In 2014, there were about 150 imprinted genes known in mice and about half that in humans. As of 2019, 260 imprinted genes have been reported in mice and 228 in humans.

Meiosis is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells with only one copy of each chromosome (haploid). Additionally, prior to the division, genetic material from the paternal and maternal copies of each chromosome is crossed over, creating new combinations of code on each chromosome. Later on, during fertilisation, the haploid cells produced by meiosis from a male and female will fuse to create a cell with two copies of each chromosome again, the zygote.

A zygote is a eukaryotic cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes. The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individual organism.

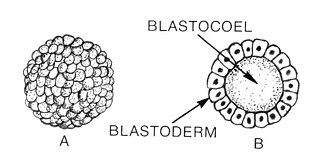

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm cell. The resulting fusion of these two cells produces a single-celled zygote that undergoes many cell divisions that produce cells known as blastomeres. The blastomeres are arranged as a solid ball that when reaching a certain size, called a morula, takes in fluid to create a cavity called a blastocoel. The structure is then termed a blastula, or a blastocyst in mammals.

Fertilisation or fertilization, also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Processes such as insemination or pollination which happen before the fusion of gametes are also sometimes informally called fertilisation. The cycle of fertilisation and development of new individuals is called sexual reproduction. During double fertilisation in angiosperms the haploid male gamete combines with two haploid polar nuclei to form a triploid primary endosperm nucleus by the process of vegetative fertilisation.

A genetic chimerism or chimera is a single organism composed of cells with more than one distinct genotype. In animals, this means an individual derived from two or more zygotes, which can include possessing blood cells of different blood types, subtle variations in form (phenotype) and, if the zygotes were of differing sexes, then even the possession of both female and male sex organs. Animal chimeras are produced by the merger of two embryos. In plant chimeras, however, the distinct types of tissue may originate from the same zygote, and the difference is often due to mutation during ordinary cell division. Normally, genetic chimerism is not visible on casual inspection; however, it has been detected in the course of proving parentage.

Blastulation is the stage in early animal embryonic development that produces the blastula. In mammalian development the blastula develops into the blastocyst with a differentiated inner cell mass and an outer trophectoderm. The blastula is a hollow sphere of cells known as blastomeres surrounding an inner fluid-filled cavity called the blastocoel. Embryonic development begins with a sperm fertilizing an egg cell to become a zygote, which undergoes many cleavages to develop into a ball of cells called a morula. Only when the blastocoel is formed does the early embryo become a blastula. The blastula precedes the formation of the gastrula in which the germ layers of the embryo form.

Mosaicism or genetic mosaicism is a condition in multicellular organisms in which a single organism possesses more than one genetic line as the result of genetic mutation. This means that various genetic lines resulted from a single fertilized egg. Genetic mosaics may often be confused with chimerism, in which two or more genotypes arise in one individual similarly to mosaicism. In chimerism, though, the two genotypes arise from the fusion of more than one fertilized zygote in the early stages of embryonic development, rather than from a mutation or chromosome loss.

In biology, a blastomere is a type of cell produced by cell division (cleavage) of the zygote after fertilization; blastomeres are an essential part of blastula formation, and blastocyst formation in mammals.

A germline mutation, or germinal mutation, is any detectable variation within germ cells. Mutations in these cells are the only mutations that can be passed on to offspring, when either a mutated sperm or oocyte come together to form a zygote. After this fertilization event occurs, germ cells divide rapidly to produce all of the cells in the body, causing this mutation to be present in every somatic and germline cell in the offspring; this is also known as a constitutional mutation. Germline mutation is distinct from somatic mutation.

Heteroplasmy is the presence of more than one type of organellar genome within a cell or individual. It is an important factor in considering the severity of mitochondrial diseases. Because most eukaryotic cells contain many hundreds of mitochondria with hundreds of copies of mitochondrial DNA, it is common for mutations to affect only some mitochondria, leaving most unaffected.

In embryology, cleavage is the division of cells in the early development of the embryo, following fertilization. The zygotes of many species undergo rapid cell cycles with no significant overall growth, producing a cluster of cells the same size as the original zygote. The different cells derived from cleavage are called blastomeres and form a compact mass called the morula. Cleavage ends with the formation of the blastula, or of the blastocyst in mammals.

Intragenomic conflict refers to the evolutionary phenomenon where genes have phenotypic effects that promote their own transmission in detriment of the transmission of other genes that reside in the same genome. The selfish gene theory postulates that natural selection will increase the frequency of those genes whose phenotypic effects cause their transmission to new organisms, and most genes achieve this by cooperating with other genes in the same genome to build an organism capable of reproducing and/or helping kin to reproduce. The assumption of the prevalence of intragenomic cooperation underlies the organism-centered concept of inclusive fitness. However, conflict among genes in the same genome may arise both in events related to reproduction and altruism.

An asymmetric cell division produces two daughter cells with different cellular fates. This is in contrast to symmetric cell divisions which give rise to daughter cells of equivalent fates. Notably, stem cells divide asymmetrically to give rise to two distinct daughter cells: one copy of the original stem cell as well as a second daughter programmed to differentiate into a non-stem cell fate.

Chromosome segregation is the process in eukaryotes by which two sister chromatids formed as a consequence of DNA replication, or paired homologous chromosomes, separate from each other and migrate to opposite poles of the nucleus. This segregation process occurs during both mitosis and meiosis. Chromosome segregation also occurs in prokaryotes. However, in contrast to eukaryotic chromosome segregation, replication and segregation are not temporally separated. Instead segregation occurs progressively following replication.

The origin and function of meiosis are currently not well understood scientifically, and would provide fundamental insight into the evolution of sexual reproduction in eukaryotes. There is no current consensus among biologists on the questions of how sex in eukaryotes arose in evolution, what basic function sexual reproduction serves, and why it is maintained, given the basic two-fold cost of sex. It is clear that it evolved over 1.2 billion years ago, and that almost all species which are descendants of the original sexually reproducing species are still sexual reproducers, including plants, fungi, and animals.

46,XX/46,XY is an exceptionally rare chimeric genetic condition characterized by the presence of some cells that express a 46,XX karyotype and some cells that express a 46,XY karyotype in a single human being. The cause of the condition lies in utero with the aggregation of two distinct blastocysts or zygotes into a single embryo, which subsequently leads to the development of a single individual with two distinct cell lines, instead of a pair of fraternal twins. 46,XX/46,XY chimeras are the result of the merging of two non-identical twins. This is not to be confused with mosaicism or hybridism, neither of which are chimeric conditions. Since individuals with the condition have two cell lines of the opposite sex, it can also be considered an intersex condition.

Cell lineage denotes the developmental history of a tissue or organ from the fertilized embryo. This is based on the tracking of an organism's cellular ancestry due to the cell divisions and relocation as time progresses, this starts with the originator cells and finishing with a mature cell that can no longer divide.

Single-cell DNA template strand sequencing, or Strand-seq, is a technique for the selective sequencing of a daughter cell's parental template strands. This technique offers a wide variety of applications, including the identification of sister chromatid exchanges in the parental cell prior to segregation, the assessment of non-random segregation of sister chromatids, the identification of misoriented contigs in genome assemblies, de novo genome assembly of both haplotypes in diploid organisms including humans, whole-chromosome haplotyping, and the identification of germline and somatic genomic structural variation, the latter of which can be detected robustly even in single cells.

Haplarithmisis is a conceptual process in Genetics that enables simultaneous haplotyping and copy-number profiling of DNA samples derived from cells. Haplarithmisis also reveals parental, segregation, and mechanistic origins of genomic anomalies. The resulting profiles of haplarithmisis are called parental haplarithms.

References

- 1 2 Destouni, Aspasia; Esteki; Catteeuw; Tšuiko; Dimitriadou; Smits; Kurg; Salumets; van Soom; Vermeesch, Joris (2016). "Zygotes segregate entire parental genomes in distinct blastomere lineages causing cleavage-stage chimerism and mixoploidy". Genome Research. 26 (5): 567–578. doi:10.1101/gr.200527.115. PMC 4864459 . PMID 27197242.

- ↑ Gabbett, M.T.; Laporte, J.; Sekar, R.; Nandini, A.; McGrath, P.; Sapkota, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, H.; Burgess, T.; Montgomery, G.W.; Chiu, R. (2019). "Molecular support for heterogonesis resulting in sesquizygotic twinning". New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (9): 842–849.

- ↑ Destouni, Aspasia; Vermeesch, Joris (2017). "How can zygotes segregate entire parental genomes into distinct blastomeres? The zygote metaphase revisited". BioEssays. 39 (4). doi:10.1002/bies.201600226. PMID 28247957. S2CID 3813188.