Asperger syndrome (AS), also known as Asperger's syndrome, formerly described a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and nonverbal communication, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. The syndrome has been merged with other disorders into autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is no longer considered a stand-alone diagnosis. It was considered milder than other diagnoses that were merged into ASD due to relatively unimpaired spoken language and intelligence.

The diagnostic category pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), as opposed to specific developmental disorders (SDD), was a group of disorders characterized by delays in the development of multiple basic functions including socialization and communication. It was defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

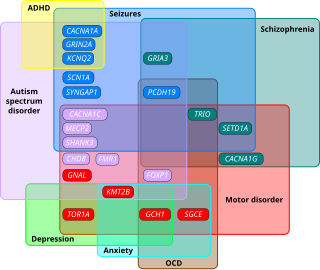

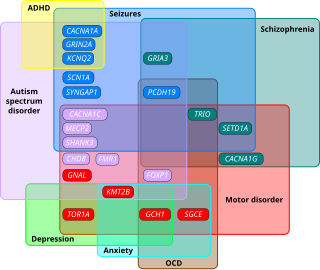

Developmental disorders comprise a group of psychiatric conditions originating in childhood that involve serious impairment in different areas. There are several ways of using this term. The most narrow concept is used in the category "Specific Disorders of Psychological Development" in the ICD-10. These disorders comprise developmental language disorder, learning disorders, motor disorders, and autism spectrum disorders. In broader definitions ADHD is included, and the term used is neurodevelopmental disorders. Yet others include antisocial behavior and schizophrenia that begins in childhood and continues through life. However, these two latter conditions are not as stable as the other developmental disorders, and there is not the same evidence of a shared genetic liability.

Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) is a historic psychiatric diagnosis first defined in 1980 that has since been incorporated into autism spectrum disorder in the DSM-5 (2013).

Childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD), also known as Heller's syndrome and disintegrative psychosis, is a rare condition characterized by late onset of developmental delays—or severe and sudden reversals—in language, social engagement, bowel and bladder, play and motor skills. Researchers have not been successful in finding a cause for the disorder. CDD has some similarities to autism and is sometimes considered a low-functioning form of it. In May 2013, CDD, along with other sub-types of PDD, was fused into a single diagnostic term called "autism spectrum disorder" under the new DSM-5 manual.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders that begin in early childhood, persist throughout adulthood, and affect three crucial areas of development: communication, social interaction and restricted patterns of behavior. There are many conditions comorbid to autism spectrum disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy.

Nonverbal learning disability (NVLD) is a proposed category of neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by core deficits in visual-spatial processing and a significant discrepancy between verbal and nonverbal intelligence. A review of papers found that proposed diagnostic criteria were inconsistent. Proposed additional diagnostic criteria include intact verbal intelligence, and deficits in the following: visuoconstruction abilities, speech prosody, fine motor coordination, mathematical reasoning, visuospatial memory and social skills. NVLD is not recognised by the DSM-5 and is not clinically distinct from learning disorder.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to autism:

Autism therapies include a wide variety of therapies that help people with autism, or their families. Such methods of therapy seek to aid autistic people in dealing with difficulties and increase their functional independence.

Self-stimulatory behavior, also known as "stimming" and self-stimulation, is the repetition of physical movements, sounds, words, moving objects, or other repetitive behaviors. Such behaviors are found to some degree in all people, especially those with developmental disabilities such as ADHD, as well as autistic people. People diagnosed with sensory processing disorder are also known to potentially exhibit stimming behaviors.

The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ) is a questionnaire published in 2001 by Simon Baron-Cohen and his colleagues at the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge, UK. Consisting of fifty questions, it aims to investigate whether adults of average intelligence have symptoms of autism spectrum conditions. More recently, versions of the AQ for children and adolescents have also been published.

In human development, muteness or mutism is defined as an absence of speech, with or without an ability to hear the speech of others. Mutism is typically understood as a person's inability to speak, and commonly observed by their family members, caregivers, teachers, doctors or speech and language pathologists. It may not be a permanent condition, as muteness can be caused or manifest due to several different phenomena, such as physiological injury, illness, medical side effects, psychological trauma, developmental disorders, or neurological disorders. A specific physical disability or communication disorder can be more easily diagnosed. Loss of previously normal speech (aphasia) can be due to accidents, disease, or surgical complication; it is rarely for psychological reasons.

Societal and cultural aspects of autism or sociology of autism come into play with recognition of autism, approaches to its support services and therapies, and how autism affects the definition of personhood. The autistic community is divided primarily into two camps; the autism rights movement and the Pathology paradigm. The pathology paradigm advocates for supporting research into therapies, treatments, and/or a cure to help minimize or remove autistic traits, seeing treatment as vital to help individuals with autism, while the neurodiversity movement believes autism should be seen as a different way of being and advocates against a cure and interventions that focus on normalization, seeing it as trying to exterminate autistic people and their individuality. Both are controversial in autism communities and advocacy which has led to significant infighting between these two camps. While the dominant paradigm is the pathology paradigm and is followed largely by autism research and scientific communities, the neurodiversity movement is highly popular among most autistic people, within autism advocacy, autism rights organizations, and related neurodiversity approaches have been rapidly growing and applied in the autism research field in the last few years.

Asperger syndrome (AS) was formerly a separate diagnosis under autism spectrum disorder. Under the DSM-5 and ICD-11, patients formerly diagnosable with Asperger syndrome are diagnosable with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The term is considered offensive by some autistic individuals. It was named after Hans Asperger (1906–80), who was an Austrian psychiatrist and pediatrician. An English psychiatrist, Lorna Wing, popularized the term "Asperger's syndrome" in a 1981 publication; the first book in English on Asperger syndrome was written by Uta Frith in 1991 and the condition was subsequently recognized in formal diagnostic manuals later in the 1990s.

Classic autism, also known as childhood autism, autistic disorder, (early) infantile autism, infantile psychosis, Kanner's autism,Kanner's syndrome, or (formerly) just autism, is a neurodevelopmental condition first described by Leo Kanner in 1943. It is characterized by atypical and impaired development in social interaction and communication as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. These symptoms first appear in early childhood and persist throughout life.

Autism, formally called autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental disorder marked by deficits in reciprocal social communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior. Other common signs include difficulties with social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, along with perseverative interests, stereotypic body movements, rigid routines, and hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input. Autism is clinically regarded as a spectrum disorder, meaning that it can manifest very differently in each person. For example, some are nonspeaking, while others have proficient spoken language. Because of this, there is wide variation in the support needs of people across the autism spectrum.

In psychiatry, stilted speech or pedantic speech is communication characterized by situationally inappropriate formality. This formality can be expressed both through abnormal prosody as well as speech content that is "inappropriately pompous, legalistic, philosophical, or quaint". Often, such speech can act as evidence for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or a thought disorder, a common symptom in schizophrenia or schizoid personality disorder.

The history of autism spans over a century; autism has been subject to varying treatments, being pathologized or being viewed as a beneficial part of human neurodiversity. The understanding of autism has been shaped by cultural, scientific, and societal factors, and its perception and treatment change over time as scientific understanding of autism develops.

The Ritvo Autism & Asperger Diagnostic Scale (RAADS) is a psychological self-rating scale developed by Dr. Riva Ariella Ritvo. An abridged and translated 14 question version was then developed at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute, to aid in the identification of patients who may have undiagnosed ASD.

Social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SPCD), also known as pragmatic language impairment (PLI), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in the social use of verbal and nonverbal communication. Individuals with SPCD struggle to effectively engage in social interactions, interpret social cues, and use language appropriately in social contexts. This disorder can have a profound impact on an individual's ability to establish and maintain relationships, navigate social situations, and participate in academic and professional settings. Although SPCD shares similarities with other communication disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), it is recognized as a distinct diagnostic category with its own set of diagnostic criteria and features.