Related Research Articles

A university constituency is a constituency, used in elections to a legislature, that represents the members of one or more universities rather than residents of a geographical area. These may or may not involve plural voting, in which voters are eligible to vote in or as part of this entity and their home area's geographical constituency.

The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1972 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland which lowered the voting age for all national elections and referendums in the state from twenty-one to eighteen years of age. It was approved by referendum on 7 December 1972 and signed into law on 5 January 1973.

The Seventh Amendment of the Constitution Act 1979 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland that provides that the procedure for the election of six members of the Senate in the university constituencies could be altered by law. It was approved by referendum on 5 July 1979 and signed into law on 3 August of the same year.

The Ninth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1984 is an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland that allowed for the extension of the right to vote in elections to Dáil Éireann to non-Irish citizens. It was approved by referendum on 14 June 1984, the same day as the European Parliament election, and signed into law on 2 August of the same year.

Amendments to the Constitution of Ireland are only possible by way of referendum. A proposal to amend the Constitution of Ireland must first be approved by both Houses of the Oireachtas (parliament), then submitted to a referendum, and finally signed into law by the President of Ireland. Since the constitution entered into force on 29 December 1937, there have been 32 amendments to the constitution.

An ordinary referendum in Ireland is a referendum on a bill other than a bill to amend the Constitution. The Constitution prescribes the process in Articles 27 and 47. Whereas a constitutional referendum is mandatory for a constitutional amendment bill, an ordinary referendum occurs only if the bill "contains a proposal of such national importance that the will of the people thereon ought to be ascertained". This is decided at the discretion of the President, after a petition by Oireachtas members including a majority of Senators. No such petition has ever been presented, and thus no ordinary referendum has ever been held.

In Ireland, direct elections by universal suffrage are used for the President, the ceremonial head of state; for Dáil Éireann, the house of representatives of the Oireachtas or parliament; for the European Parliament; and for local government. All elections use proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote (PR-STV) in constituencies returning three or more members, except that the presidential election and by-elections use the single-winner analogue of STV, elsewhere called instant-runoff voting or the alternative vote. Members of Seanad Éireann, the second house of the Oireachtas, are partly nominated, partly indirectly elected, and partly elected by graduates of particular universities.

The Oireachtas of the Irish Free State was the legislature of the Irish Free State from 1922 until 1937. It was established by the 1922 Constitution of Ireland which was based from the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It was the first independent Irish Parliament officially recognised outside Ireland since the historic Parliament of Ireland which was abolished with the Acts of Union 1800.

The current Constitution of Ireland came into effect on 29 December 1937, repealing and replacing the Constitution of the Irish Free State, having been approved in a national plebiscite on 1 July 1937 with the support of 56.5% of voters in the then Irish Free State. The Constitution was closely associated with Éamon de Valera, the President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State at the time of its approval.

National University of Ireland (NUI) is a university constituency in Ireland, which currently elects three senators to Seanad Éireann. Its electorate is the graduates of the university, which has a number of constituent universities. It previously elected members to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom (1918–1921), to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland (1921) and to Dáil Éireann (1918–1936).

Dublin University is a university constituency in Ireland, which currently elects three senators to Seanad Éireann. Its electorate comprises the undergraduate scholars and graduates of the University of Dublin, whose sole constituent college is Trinity College Dublin, so it is often also referred to as the Trinity College constituency. Between 1613 and 1937 it elected MPs or TDs to a series of representative legislative bodies.

A vocational panel is any of five lists of candidates from which are elected a total of 43 of the 60 senators in Seanad Éireann, the upper house of the Oireachtas (parliament) of Ireland. Each panel corresponds to a grouping of "interests and services" of which candidates are required to have "knowledge and practical experience". The panels are nominated partly by Oireachtas members and partly by vocational organisations. From each panel, between five and eleven senators are elected indirectly, by Oireachtas members and local councillors, using the single transferable vote. The broad requirements are specified by Article 18 of the Constitution of Ireland and the implementation details by acts of the Oireachtas, principally the Seanad Electoral Act 1947, and associated statutory instruments.

The Constituency Commission is an independent commission in Ireland which had advised on redrawing of constituency boundaries of Dáil constituencies for the election of members to Dáil Éireann and European Parliament constituencies prior to the establishment of the Electoral Commission in 2023. Each commission was established by the Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government after the census. The Commission then submitted a non-binding report to the Oireachtas, and was dissolved. A separate but similar Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee fulfilled the same function for local electoral area boundaries of local government areas.

An election for 19 of the 60 seats in Seanad Éireann, the Senate of the Irish Free State, was held on 17 September 1925. The election was by single transferable vote, with the entire state forming a single 19-seat electoral district. There were 76 candidates on the ballot paper, whom voters ranked by preference. Of the two main political parties, the larger did not formally endorse any candidates, while the other boycotted the election. Voter turnout was low and the outcome was considered unsatisfactory. Subsequently, senators were selected by the Oireachtas rather than the electorate.

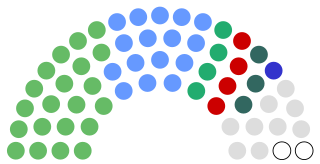

Seanad Éireann is the upper house of the Oireachtas, which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann.

The Electoral Act 1923 was a law in Ireland which established the electoral law of the Irish Free State and provided for parliamentary constituencies in Dáil Éireann.

The Constitution Act 1936 was an Act of the Oireachtas of the Irish Free State amending the Constitution of the Irish Free State which had been adopted in 1922. It abolished the two university constituencies in Dáil Éireann.

At most elections in the Republic of Ireland the electoral register is based on residential address, and the only nonresident voters are those serving abroad on government business; this includes Irish diplomats and their spouses, and Defence Forces and Garda Síochána personnel but not their spouses. An exception is in elections to the Seanad for which graduates voting in the university constituencies may be nonresident. A government bill introduced in 2019 proposed allowing nonresident citizens to vote in presidential elections.

Various proposals have been considered since the 1980s to extend the franchise in Irish presidential elections to citizens resident outside the state. In 2019, the then government introduced a bill to amend the constitution to facilitate this extension. The bill lapsed in January 2020 when the 32nd Dáil was dissolved for the 2020 general election, but was restored to the order paper in July 2020.

References

Sources

Citations

- ↑ Johnston-Liik, E. M. (1 January 2007). Commons, Constituencies and Statutes. History of the Irish Parliament 1692-1800. Vol. VI. Ulster Historical Foundation. p. 124. ISBN 9781903688717 . Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ 2 Anne c.6 s.24; Simms 1960, p.35

- ↑ 2 George I c.19 s.7; Simms 1960, p.32

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Land and Politics". UK Parliament. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Irishwomen and the Franchise". Dáil Éireann (2nd Dáil). Oireachtas. 2 March 1922. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ McCarthy, Cal (3 April 2007). "Division and Civil War 1921–23". Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution. Collins Press. ISBN 9781848898608 . Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ "National Coalition Panel : Joint Statement". Dáil Éireann (2nd Dáil). Oireachtas. 20 May 1922. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Constitution of the Irish Free State". Irish Statute Book . Article 14. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ "Fourth Amendment of the Constitution Bill 1972: Second Stage". Dáil Éireann debates. 5 July 1972. pp. Vol.262 No.5 p.6 cc.672–703. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ "Constabulary (Ireland) Act 1836". Irish Statute Book . sec.18. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ "Dublin Police Act 1836". Irish Statute Book . sec.19. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Disqualifications — Committee Stage". Dáil Éireann debates. 15 November 1922. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Emsley, Clive (19 September 2014). The English Police: A Political and Social History. Taylor & Francis. p. 128. ISBN 9781317890232 . Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Police Disabilities Removal Acts 1887 and 1893 (franchise for parliamentary and local elections respectively)

- ↑ Coakley, John; Gallagher, Michael (2017). Politics in the Republic of Ireland. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 9781317312697 . Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ↑ "Electoral Act, 1923, Section 5". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 4 December 2015.; "Electoral Act, 1960". Irish Statute Book . pp. sec.3 and Schedule. Retrieved 4 December 2015.; "Private Members' Business. - Garda Síochána Franchise—Motion". Dáil Éireann debates. Oireachtas. 2 November 1955. Retrieved 8 December 2015.; Blaney, Neil (6 December 1960). "Electoral Bill 1960 — Second Stages". Dáil Éireann debates. Oireachtas. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

One of the important proposals is contained in Section 3 and in the Schedule which provides for the repeal of the prohibition on the registration of Gardaí as voters at Dáil elections. In future, if this provision is enacted, Gardaí can vote at Dáil and presidential elections and at referendums.

- ↑ "Constitution (Amendment No. 6) Act, 1928". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ Coakley, John (September 2005). "Ireland's Unique Electoral Experiment: The Senate Election of 1925". Irish Political Studies. 20 (3): 231–269. doi:10.1080/07907180500359327. S2CID 145175747.

- ↑ "Local Government (Extension of Franchise) Act, 1935, Section 2". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ "Fourth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1972, Section 1". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Electoral (Amendment) Act 1985, Section 2". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ Supreme Court of Ireland (8 February 1984). "In the Matter of Article 26 of the Constitution and in the Matter of The Electoral (Amendment) Bill 1983 [S.C. No. 373 of 1983]". Dublin: Courts Service. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ "Electoral Act 1992, Section 8". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Written Answers No. 505: Electoral Reform". Dáil Éireann debates. 27 May 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Honohan, Iseult (2011). "Should Irish Emigrants have Votes? External Voting in Ireland" (PDF). Irish Political Studies. 26 (4): 545–561 : p.14 of preprint. doi:10.1080/07907184.2011.619749. hdl: 10197/4346 . ISSN 0790-7184. S2CID 154639410.; Kenny, Ciara (13 November 2014). "Irish emigrants should have right to vote, report says". The Irish Times . Retrieved 23 April 2018.; "Coveney publishes an Options Paper on extending the eligibility for citizens resident outside the State to vote at presidential elections". MerrionStreet (Press release). Government of Ireland. 22 March 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2018.; Ruth, Maguire. "Announcement by the Taoiseach on Voting Rights in Presidential Elections for Irish Citizens outside the State" (Press release). Department of the Taoiseach. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ Electoral (Amendment) Act 2006 ( No. 33 of 2006 ). Enacted on 11 December 2006. Act of the Oireachtas .Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 10 December 2015.

- ↑ Molony, Senan (23 October 2006). "Inmates to vote by post in next election". Irish Independent . Retrieved 14 December 2015.

The Irish situation has been that prisoners are not legally denied the vote, but have had no opportunity of taking up this right.

- ↑ Michael McDowell, Joe O'Toole, Noel Whelan, Feargal Quinn and Katherine Zappone (26 September 2012). "Options For A More Democratic Seanad Through Legislative Change" (PDF). Radical seanad reform through legislative change. p. 25; §7.2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "CONSTITUTION OF IRELAND". Irish Statute Book . Retrieved 10 December 2015.