Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist., venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reformation of the Benedictine Order through the nascent Cistercian Order.

Pope Celestine II, born Guido di Castello, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 26 September 1143 to his death in 1144.

Year 1118 (MCXVIII) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

The Cistercians, officially the Order of Cistercians, are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contributions of the highly-influential Bernard of Clairvaux, known as the Latin Rule. They are also known as Bernardines, after Saint Bernard himself, or as White Monks, in reference to the colour of the "cuculla" or cowl worn by the Cistercians over their habits, as opposed to the black cowl worn by Benedictines.

Guillaume de Champeaux, known in English as William of Champeaux and Latinised to Gulielmus de Campellis, was a French philosopher and theologian.

Héloïse, variously Héloïse d'Argenteuil or Héloïse du Paraclet, was a French nun, philosopher, writer, scholar, and abbess.

Henry of Lausanne was a French heresiarch of the first half of the 12th century. His preaching began around 1116 and he died imprisoned around 1148. His followers are known as Henricians.

Walter of Mortagne was a Scholastic philosopher and Catholic theologian.

Peter the Venerable, also known as Peter of Montboissier, was the abbot of the Benedictine abbey of Cluny. He has been honored as a saint, though he was never canonized in the Middle Ages. Since in 1862 Pope Pius IX confirmed his historical cult, and the Martyrologium Romanum, issued by the Holy See in 2004, regards him as a Blessed.

Robert of Melun was an English scholastic Christian theologian who taught in France, and later became Bishop of Hereford in England. He studied under Peter Abelard in Paris before teaching there and at Melun, which gave him his surname. His students included John of Salisbury, Roger of Worcester, William of Tyre, and possibly Thomas Becket. Robert was involved in the Council of Reims in 1148, which condemned the teachings of Gilbert de la Porrée. Three of his theological works survive, and show him to have been strictly orthodox.

Alberic of Ostia (1080–1148) was a Benedictine monk, and Cardinal Bishop of Ostia from 1138 to 1148.

Eskil was a 12th-century Archbishop of Lund, in Skåne, Denmark.

The Councils of Sens were a number of church councils hosted by the Archdiocese of Sens.

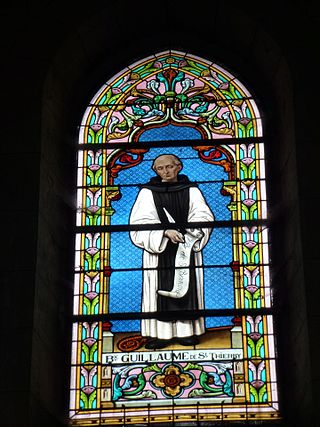

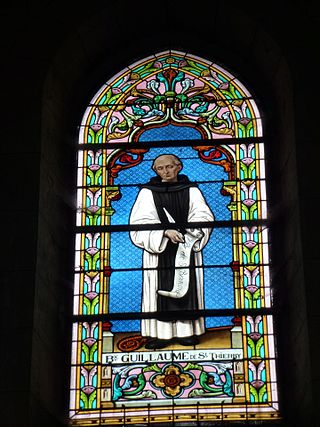

William of Saint-Thierry, O. Cist was a twelfth-century Benedictine, theologian and mystic from Liège who became abbot of Saint-Thierry in France, and later joined the Cistercian Order.

Christianity in the 12th century was marked by scholastic development and monastic reforms in the western church and a continuation of the Crusades, namely with the Second Crusade in the Holy Land.

The Abbey of Santa Maria di Rovegnano is a Cistercian monastic complex in the comune of Milan, Lombardy, northern Italy. The borgo that has developed round the abbey was once an independent commune called Chiaravalle Milanese, now included in Milan and referred to as the Chiaravalle district.

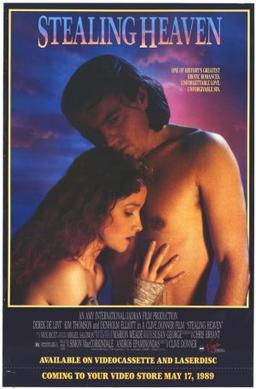

Stealing Heaven is a 1988 film directed by Clive Donner and starring Derek de Lint, Kim Thomson and Denholm Elliott. It is a costume drama based on the French 12th-century medieval romance of Peter Abelard and Héloïse and on a historical novel by Marion Meade. This was Donner's final theatrical film, before his death in 2010.

Jean LeclercqOSB, was a French Benedictine monk, the author of classic studies on Lectio Divina and the history of inter-monastic dialogue, as well as the life and theology of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. LeClercq is perhaps best known in the English speaking world for his seminal work The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture.

Peter Abelard was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician.

Berengar of Poitiers was a younger contemporary and zealous adherent of the philosopher Peter Abelard. Practically nothing is known of his life except what may be learned from his few brief writings. His byname, Pictauensis in Latin, indicates that he had some association with Poitou; probably he was born there. He was a member of the secular clergy.