Related Research Articles

In economics, the Gini coefficient, also known as the Gini index or Gini ratio, is a measure of statistical dispersion intended to represent the income inequality, the wealth inequality, or the consumption inequality within a nation or a social group. It was developed by Italian statistician and sociologist Corrado Gini.

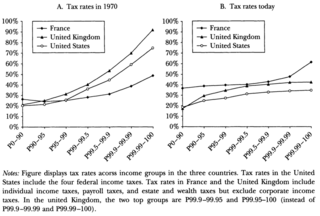

A progressive tax is a tax in which the tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases. The term progressive refers to the way the tax rate progresses from low to high, with the result that a taxpayer's average tax rate is less than the person's marginal tax rate. The term can be applied to individual taxes or to a tax system as a whole. Progressive taxes are imposed in an attempt to reduce the tax incidence of people with a lower ability to pay, as such taxes shift the incidence increasingly to those with a higher ability-to-pay. The opposite of a progressive tax is a regressive tax, such as a sales tax, where the poor pay a larger proportion of their income compared to the rich

Economic inequality is an umbrella term for a) income inequality or distribution of income, b) wealth inequality or distribution of wealth, and c) consumption inequality. Each of these can be measured between two or more nations, within a single nation, or between and within sub-populations.

Social mobility is the movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society. It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given society. This movement occurs between layers or tiers in an open system of social stratification. Open stratification systems are those in which at least some value is given to achieved status characteristics in a society. The movement can be in a downward or upward direction. Markers for social mobility such as education and class, are used to predict, discuss and learn more about an individual or a group's mobility in society.

In economics, income distribution covers how a country's total GDP is distributed amongst its population. Economic theory and economic policy have long seen income and its distribution as a central concern. Unequal distribution of income causes economic inequality which is a concern in almost all countries around the world.

Income inequality metrics or income distribution metrics are used by social scientists to measure the distribution of income and economic inequality among the participants in a particular economy, such as that of a specific country or of the world in general. While different theories may try to explain how income inequality comes about, income inequality metrics simply provide a system of measurement used to determine the dispersion of incomes. The concept of inequality is distinct from poverty and fairness.

Economic mobility is the ability of an individual, family or some other group to improve their economic status—usually measured in income. Economic mobility is often measured by movement between income quintiles. Economic mobility may be considered a type of social mobility, which is often measured in change in income.

In economics, personal income refers to the total earnings of an individual from various sources such as wages, investment ventures, and other sources of income. It encompasses all the products and money received by an individual.

The Nordic model comprises the economic and social policies as well as typical cultural practices common in the Nordic countries. This includes a comprehensive welfare state and multi-level collective bargaining based on the economic foundations of social corporatism, and a commitment to private ownership within a market-based mixed economy—with Norway being a partial exception due to a large number of state-owned enterprises and state ownership in publicly listed firms.

Income inequality has fluctuated considerably in the United States since measurements began around 1915, moving in an arc between peaks in the 1920s and 2000s, with a 30-year period of relatively lower inequality between 1950 and 1980.

Social inequality occurs when resources within a society are distributed unevenly, often as a result of inequitable allocation practices that create distinct unequal patterns based on socially defined categories of people. Differences in accessing social goods within society are influenced by factors like power, religion, kinship, prestige, race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, and class. Social inequality usually implies the lack of equality of outcome, but may alternatively be conceptualized as a lack of equality in access to opportunity.

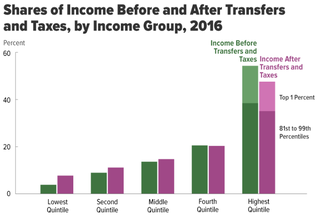

Redistribution of income and wealth is the transfer of income and wealth from some individuals to others through a social mechanism such as taxation, welfare, public services, land reform, monetary policies, confiscation, divorce or tort law. The term typically refers to redistribution on an economy-wide basis rather than between selected individuals.

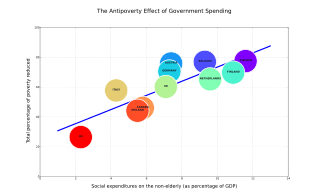

The effects of social welfare on poverty have been the subject of various studies.

Socioeconomic mobility in the United States refers to the upward or downward movement of Americans from one social class or economic level to another, through job changes, inheritance, marriage, connections, tax changes, innovation, illegal activities, hard work, lobbying, luck, health changes or other factors.

The "Great Gatsby Curve" is the term given to the positive empirical relationship between cross-sectional income inequality and persistence of income across generations. The scatter plot shows the relationship between income inequality in a country and intergenerational income mobility.

Sweden enjoys a relatively low income inequality and a high standard of living. Unemployment as of 2017 was estimated to be 6.6% by the CIA World Fact Book, lower than in other European Union countries. The Nordic model of a social welfare society exemplified by Sweden and its near neighbours has often been considered a European success story compared internationally with the socioeconomic structures of other developed industrial nations. This model of state provided social welfare includes many unemployment benefits for the poor, and amply funded health, housing and social security provision. within essentially corruption free nations subscribing to principles of a measure of openness of information about government activity. The Income inequality in Sweden ranks low in the Gini coefficient, being 25.2 as of 2015 which is one of the lowest in the world, and ranking similarly to the other Nordic countries; although inequality has recently been on the rise and several central European countries now have a lower Gini coefficient than Sweden.

Effects of income inequality, researchers have found, include higher rates of health and social problems, and lower rates of social goods, a lower population-wide satisfaction and happiness and even a lower level of economic growth when human capital is neglected for high-end consumption. For the top 21 industrialised countries, counting each person equally, life expectancy is lower in more unequal countries. A similar relationship exists among US states.

Poverty in Norway had been declining from World War II until the Global Financial Crisis. It is now increasing slowly, and is significantly higher among immigrants from the Middle East and Africa. Before an analysis of poverty can be undertaken, the definition of poverty must first be established, because it is a subjective term. The measurement of poverty in Norway deviates from the measurement used by the OECD. Norway traditionally has been a global model and leader in maintaining low levels on poverty and providing a basic standard of living for even its poorest citizens. Norway combines a free market economy with the welfare model to ensure both high levels of income and wealth creation and equal distribution of this wealth. It has achieved unprecedented levels of economic development, equality and prosperity.

References

- 1 2 3 Rueda, David; Pontusson, Jonas (2000-04-01). "Wage Inequality and Varieties of Capitalism". World Politics. 52 (3): 350–383. doi:10.1017/S0043887100016579. ISSN 1086-3338.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smidova, Zuzana; Klein, Caroline; Ruiz, Nicolas; Hermansen, Mikkel; Causa, Orsetta (2016). "Inequality in Denmark through the Looking Glass" (PDF). OECD Economics Department Working Papers. doi:10.1787/5jln041vm6tg-en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Income Inequality". Archived from the original on 2019-09-18.

- ↑ "skill-biased technical change" (PDF). NYU.edu. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Corak, Miles (2013). "Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 27 (3): 79–102. doi: 10.1257/jep.27.3.79 . hdl: 10419/80702 . JSTOR 41955546.

- ↑ "This Chart Makes A Joke Out Of The American Dream". Business Insider.

- ↑ Bratsberg, Bernt; Røed, Knut; Raaum, Oddbjørn; Naylor, Robin; Ja¨ntti, Markus; Eriksson, Tor; O¨sterbacka, Eva (1 March 2007). "Nonlinearities in Intergenerational Earnings Mobility: Consequences for Cross-Country Comparisons*". The Economic Journal. 117 (519): C72–C92. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.545.9052 . doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02036.x. ISSN 1468-0297. S2CID 16653479.

- ↑ Corak, Miles; Piraino, Patrizio (19 April 2010). "Intergenerational Earnings Mobility and the Inheritance of Employers". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 1591703.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Corak, Miles; Piraino, Patrizio (2011). "The Intergenerational Transmission of Employers". Journal of Labor Economics. 29 (1): 37–68. doi:10.1086/656371. hdl: 10419/36086 . S2CID 14049279.

- 1 2 3 Breen, Richard; Andersen, Signe Hald (2012). "Educational Assortative Mating and Income Inequality in Denmark". Demography. 49 (3): 867–887. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0111-2 . JSTOR 23252675. PMID 22639010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "World Happiness Report 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-22.

- 1 2 3 Alesina, Alberto; Di Tella, Rafael; MacCulloch, Robert (2004-08-01). "Inequality and happiness: are Europeans and Americans different?". Journal of Public Economics. 88 (9–10): 2009–2042. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.203.664 . doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.07.006.

- 1 2 Kenworthy, Lane (2008). Jobs with Equality. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-19-955059-3.

- 1 2 Veenhoven, Ruut; Kalmijn, Wim (2005). "Inequality-Adjusted Happiness in Nations Egalitarianism and Utilitarianism Married in a New Index of Societal Performance". Journal of Happiness Studies. 6 (4): 421–455. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-8857-5. hdl: 1765/7204 . ISSN 1389-4978. S2CID 53500428.

- ↑ "I dream of Gini". The Economist. 2011-10-12.

- 1 2 3 Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780069028573.