Naturalization is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the United Nations excludes citizenship that is automatically acquired or is acquired by declaration. Naturalization usually involves an application or a motion and approval by legal authorities. The rules of naturalization vary from country to country but typically include a promise to obey and uphold that country's laws and taking and subscribing to an oath of allegiance, and may specify other requirements such as a minimum legal residency and adequate knowledge of the national dominant language or culture. To counter multiple citizenship, some countries require that applicants for naturalization renounce any other citizenship that they currently hold, but whether this renunciation actually causes loss of original citizenship, as seen by the host country and by the original country, will depend on the laws of the countries involved.

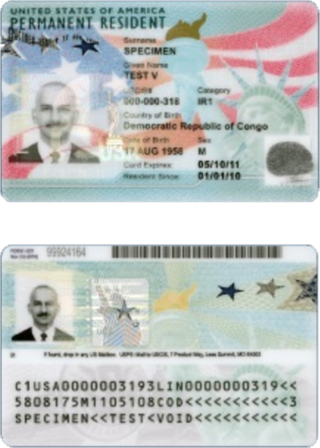

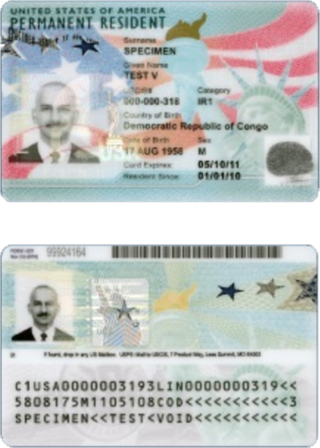

A green card, known officially as a permanent resident card, is an identity document which shows that a person has permanent residency in the United States. Green card holders are formally known as lawful permanent residents (LPRs). As of 2019, there are an estimated 13.9 million green card holders, of whom 9.1 million are eligible to become United States citizens. Approximately 18,700 of them serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Permanent residency is a person's legal resident status in a country or territory of which such person is not a citizen but where they have the right to reside on a permanent basis. This is usually for a permanent period; a person with such legal status is known as a permanent resident. In the United States, such a person is referred to as a green card holder but more formally as a Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR).

A British Overseas citizen (BOC) is a holder of a residual class of British nationality, largely held by people connected with former British colonies who do not have close ties to the United Kingdom or its remaining overseas territories. Individuals with this form of nationality are British nationals and Commonwealth citizens, but not British citizens. BOCs are subject to immigration control when entering the United Kingdom and do not have the automatic right of abode there or in any British overseas territory.

The right of abode is an individual's freedom from immigration control in a particular country. A person who has the right of abode in a country does not need permission from the government to enter the country and can live and work there without restriction, and is immune from removal and deportation.

Belonger status is a legal classification normally associated with British Overseas Territories. It refers to people who have close ties to a specific territory, normally by birth or ancestry. The requirements for belonger status, and the rights that it confers, vary from territory to territory.

This article concerns the history of British nationality law.

A UK Ancestry visa is a visa issued by the United Kingdom to Commonwealth citizens with a grandparent born in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands, Isle of Man or Ireland who wish to work in the United Kingdom. It is used mainly by young Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders and South Africans of British descent coming to the UK to work and as a base to explore Europe.

A British Overseas Territories citizen (BOTC), formerly called British Dependent Territories citizen (BDTC), is a member of a class of British nationality granted to people connected with one or more of the British Overseas Territories.

The right of abode (ROA) is an immigration status in the United Kingdom that gives a person the unrestricted right to enter and live in the UK. It was introduced by the Immigration Act 1971 which went into effect on 1 January 1973. This status is held by British citizens, certain British subjects, as well as certain Commonwealth citizens with specific connections to the UK before 1983. Since 1983, it is not possible for a person to acquire this status without being a British citizen.

Danish nationality law is governed by the Constitutional Act and the Consolidated Act of Danish Nationality. Danish nationality can be acquired in one of the following ways:

The primary law governing nationality in the United Kingdom is the British Nationality Act 1981, which came into force on 1 January 1983. Regulations apply to the British Islands, which include the UK itself and the Crown dependencies, and the 14 British Overseas Territories.

The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It received royal assent on 7 November 2002.

The British National (Overseas) passport, commonly referred to as the BN(O) passport, is a British passport for people with British National (Overseas) status. BN(O) status was created in 1987 after the enactment of Hong Kong Act 1985, whose holders are permanent residents of Hong Kong who were British Overseas Territories citizens until 30 June 1997 and had registered as BN(O)s.

In tertiary education in the United Kingdom, the term home student is used to refer to those who are eligible to pay university tuition fees at a lower rate than overseas students. In general, British, and Irish citizens qualify for home student status only if they have been "ordinarily resident" in the UK for three years prior to the start of university. From Autumn 2021, EU citizens lost their home student status and since have had to pay the higher international tuition fees. There are other criteria to be satisfied. All other students, even British citizens, who do not qualify as "home students" are considered to be overseas students and must pay higher overseas students tuition fees at university.

The visa policy of the United Kingdom is the policy by which His Majesty's Government determines visa requirements for visitors to the United Kingdom, and the Crown dependencies of Guernsey, Jersey, and the Isle of Man and those seeking to work, study or reside there.

The Immigration Regulations 2016, or EEA Regulations 2016 for short, constituted the law that implemented the right of free movement of European Economic Area (EEA) nationals and their family members in the United Kingdom. The regulations were repealed by the Immigration and Social Security Co-ordination Act 2020 on 31 December 2020, at the end of the transition period.

The European Union Settlement Scheme is an immigration regime of the United Kingdom introduced by the Home Office in 2019, under the new Appendix EU of the UK's Immigration Rules, in response to the Brexit situation. EUSS processes the registration of nationals of EU and EFTA countries who were resident in the United Kingdom prior to the end of the Brexit transition/implementation period at 11pm GMT on 31 December 2020. Successful applicants receive either 'pre-settled status' or 'settled status', generally depending on the length of time they have been resident in the United Kingdom.

Immigration policies of the United Kingdom are the areas of modern British policy concerned with the immigration system of the United Kingdom—primarily, who has the right to visit or stay in the UK. British immigration policy is under the purview of UK Visas and Immigration.

The British Certificate of Travel is an international travel document and a type of Home Office travel document issued by the UK Home Office to non-citizen residents of United Kingdom who are unable to obtain a national passport or other conventional travel documents. Until 17 March 2008, the Certificate of Travel was called a Certificate of Identity. It is usually valid for five years, or if the holder only has temporary permission to stay in the United Kingdom, the validity will be identical to the length of stay permitted.