The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed the president to imprison and deport non-citizens, the Alien Enemies Act gave the president additional powers to detain non-citizens during times of war, and the Sedition Act criminalized false and malicious statements about the federal government. The Alien Friends Act and the Sedition Act expired after a set number of years, and the Naturalization Act was repealed in 1802. The Alien Enemies Act is still in effect.

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River – specifically, to a designated Indian Territory. The Indian Removal Act, the key law which authorized the removal of Native tribes, was signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830. Although Jackson took a hard line on Indian removal, the law was enforced primarily during the Martin Van Buren administration. After the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, approximately 60,000 members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands, with thousands dying during the Trail of Tears.

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or approximately eighteen dollars per square mile, the United States nominally acquired a total of 828,000 sq mi in Middle America. However, France only controlled a small fraction of this area, most of which was inhabited by Native Americans; effectively, for the majority of the area, the United States bought the "preemptive" right to obtain "Indian" lands by treaty or by conquest, to the exclusion of other colonial powers.

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the Southeastern United States to newly designated Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. The Cherokee removal in 1838 was brought on by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1828, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush.

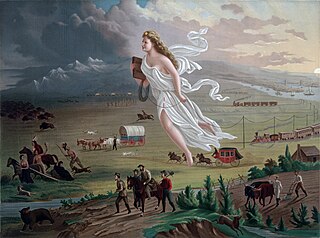

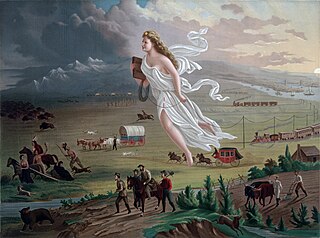

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

Fort Madison is a city and a county seat of Lee County, Iowa, United States along with Keokuk. Of Iowa's 99 counties, Lee County is the only one with two county seats. The population was 10,270 at the time of the 2020 census. Located along the Mississippi River in the state's southeast corner, it lies between small bluffs along one of the widest portions of the river.

The Treaty of Ghent was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands. The treaty restored relations between the two parties to status quo ante bellum by restoring the pre-war borders of June 1812.

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted war, resolved issues remaining since the Treaty of Paris of 1783, and facilitated ten years of peaceful trade between the United States and Britain in the midst of the French Revolutionary Wars, which began in 1792. The Treaty was designed by Alexander Hamilton and supported by President George Washington. It angered France and bitterly divided Americans. It inflamed the new growth of two opposing parties in every state, the pro-Treaty Federalists and the anti-Treaty Jeffersonian Republicans.

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, which meant opposition to what they considered to be artificial aristocracy, opposition to corruption, and insistence on virtue, with a priority for the "yeoman farmer", "planters", and the "plain folk". They were antagonistic to the aristocratic elitism of merchants, bankers, and manufacturers, distrusted factory workers, and were on the watch for supporters of the Westminster system.

Black Hawk, born Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, was a Sauk leader and warrior who lived in what is now the Midwestern United States. Although he had inherited an important historic sacred bundle from his father, he was not a hereditary civil chief. Black Hawk earned his status as a war chief or captain by his actions: leading raiding and war parties as a young man and then a band of Sauk warriors during the Black Hawk War of 1832.

The origins of the War of 1812 (1812-1815), between the United States and the British Empire and its First Nation allies, have been long debated. The War of 1812 was caused by multiple factors and ultimately led to the US declaration of war on Britain:

Fort Armstrong (1816–1836), was one of a chain of western frontier defenses which the United States erected after the War of 1812. It was located at the foot of Rock Island, in the Mississippi River near the present-day Quad Cities of Illinois and Iowa. It was five miles from the principal Sac and Fox village on Rock River in Illinois. Of stone and timber construction, 300 feet square, the fort was begun in May 1816 and completed the following year. In 1832, the U.S. Army used the fort as a military headquarters during the Black Hawk War. It was normally garrisoned by two companies of United States Army regulars. With the pacification of the Indian threat in Illinois, the U.S. Government ceased operations at Fort Armstrong and the U.S. Army abandoned the frontier fort in 1836.

The presidency of George Washington began on April 30, 1789, when Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1797. Washington took office after the 1788–1789 presidential election, the nation's first quadrennial presidential election, in which he was elected unanimously. Washington was re-elected unanimously in the 1792 presidential election, and chose to retire after two terms. He was succeeded by his vice president, John Adams of the Federalist Party.

Federal Indian policy establishes the relationship between the United States Government and the Indian Tribes within its borders. The Constitution gives the federal government primary responsibility for dealing with tribes. Some scholars divide the federal policy toward Indians in six phases: coexistence (1789–1828), removal and reservations (1829–1886), assimilation (1887–1932), reorganization (1932–1945), termination (1946–1960), and self-determination (1961–1985).

American political ideologies conventionally align with the left–right political spectrum, with most Americans identifying as conservative, liberal, or moderate. Contemporary American conservatism includes social conservatism, classical liberalism and economic liberalism. The former ideology developed as a response to communism and the civil rights movement, while the latter two ideologies developed as a response to the New Deal. Contemporary American liberalism includes progressivism, welfare capitalism and social liberalism, developing during the Progressive Era and the Great Depression. Besides modern conservatism and liberalism, the United States has a notable libertarian movement, and historical political movements in the United States have been shaped by ideologies as varied as republicanism, populism, separatism, socialism, monarchism, and nationalism.

The Meriam Report (1928) was commissioned by the Institute for Government Research and funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. The IGR appointed Lewis Meriam to be the technical director of the survey team to compile information and report of the conditions of American Indians across the country. Meriam submitted the 847-page report to the Secretary of the Interior, Hubert Work, on February 21, 1928.

The Indian Peace Commission was a group formed by an act of Congress on July 20, 1867 "to establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes." It was composed of four civilians and three, later four, military leaders. Throughout 1867 and 1868, they negotiated with a number of tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, Kiowa-Apache, Cheyenne, Lakota, Navajo, Snake, Sioux, and Bannock. The treaties that resulted were designed to move the tribes to reservations, to "civilize" and assimilate these native peoples, and transition their societies from a nomadic to an agricultural existence.

Thomas Jefferson believed Native American peoples to be a noble race who were "in body and mind equal to the whiteman" and were endowed with an innate moral sense and a marked capacity for reason. Nevertheless, he believed that Native Americans were culturally and technologically inferior. Like many contemporaries, he believed that Indian lands should be taken over by white people.

The Progress of Civilization is a marble pediment above the entrance to the Senate wing of the United States Capitol building designed by the sculptor Thomas Crawford. An allegorical personification of America stands at the center of the pediment. To her right, a white woodsman clears the wilderness inhabited by a Native American boy, father, mother, and child. The left side of the pediment depicts a soldier, a merchant, two schoolchildren, a teacher with her pupil, and a mechanic.

The United States Government Fur Trade Factory System was a system of government trading without profit with Native Americans that existed between 1795 and 1821.