Richard McGarrah Helms was an American government official and diplomat who served as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) from 1966 to 1973. Helms began intelligence work with the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. Following the 1947 creation of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), he rose in its ranks during the presidencies of Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy. Helms then was DCI under Presidents Johnson and Nixon, yielding to James R. Schlesinger in early 1973.

The director of central intelligence (DCI) was the head of the American Central Intelligence Agency from 1946 to 2004, acting as the principal intelligence advisor to the president of the United States and the United States National Security Council, as well as the coordinator of intelligence activities among and between the various US intelligence agencies.

The United States Intelligence Community (IC) is a group of separate United States government intelligence agencies and subordinate organizations that work both separately and collectively to conduct intelligence activities which support the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States. Member organizations of the IC include intelligence agencies, military intelligence, and civilian intelligence and analysis offices within federal executive departments.

A covert operation or undercover operation is a military or police operation involving a covert agent or troops acting under an assumed cover to conceal the identity of the party responsible. Some of the covert operations are also clandestine operations which are performed in secret and meant to stay secret, though many are not.

In the United States, a presidential finding, more formally known as a Memorandum of Notification (MON), is a presidential directive required by statute to be delivered to certain Congressional committees to justify the commencement of covert operations by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The Hughes–Ryan Amendment was an amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, passed as section 32 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1974. The amendment was named for its co-authors, Senator Harold E. Hughes (D–IA) and Representative Leo Ryan (D–CA). The amendment required the President of the United States to report all covert actions of the Central Intelligence Agency to one or more Congressional committees.

The Directorate of Operations (DO), less formally called the Clandestine Service, is a component of the US Central Intelligence Agency. It was known as the Directorate of Plans from 1951 to 1973; as the Directorate of Operations from 1973 to 2005; and as the National Clandestine Service (NCS) from 2005 to 2015.

Operation CHAOS or Operation MHCHAOS was a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) domestic espionage project targeting American citizens operating from 1967 to 1974, established by President Lyndon B. Johnson and expanded under President Richard Nixon, whose mission was to uncover possible foreign influence on domestic race, anti-war, and other protest movements. The operation was launched under Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Richard Helms by chief of counter-intelligence James Jesus Angleton, and headed by Richard Ober. The "MH" designation is to signify the program had a global area of operations.

The Central Intelligence Agency, known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, and analyzing national security information from around the world, primarily through the use of human intelligence (HUMINT) and conducting covert action through its Directorate of Operations. As a principal member of the United States Intelligence Community (IC), the CIA reports to the Director of National Intelligence and is primarily focused on providing intelligence for the President and Cabinet of the United States. Following the dissolution of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) at the end of World War II, President Harry S. Truman created the Central Intelligence Group under the direction of a Director of Central Intelligence by presidential directive on January 22, 1946, and this group was transformed into the Central Intelligence Agency by implementation of the National Security Act of 1947.

Executive oversight of United States covert operations has been carried out by a series of sub-committees of the National Security Council (NSC).

The Dulles–Jackson–Correa Report was one of the most influential evaluations of the functioning of the United States Intelligence Community, and in particular, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The report focused primarily on the coordination and organization of the CIA and offered suggestions that refined the US intelligence effort in the early stages of the Cold War.

The Schlesinger Report, originally titled A Review of the Intelligence Community, was the product of a survey authorized by U.S. President Richard Nixon late in 1970. The objective of the survey was to identify and alleviate factors of ineffectiveness within the United States Intelligence Community (IC) organization, planning, and preparedness for future growth. The report, prepared by James Schlesinger, Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), was submitted to Nixon on 10 March 1971.

At various times since the creation of the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal government of the United States has produced comprehensive reports on CIA actions that marked historical watersheds in how CIA went about trying to fulfill its vague charter purposes from 1947. These reports were the result of internal or presidential studies, external investigations by congressional committees or other arms of the Federal government of the United States, or even the simple releases and declassification of large quantities of documents by the CIA.

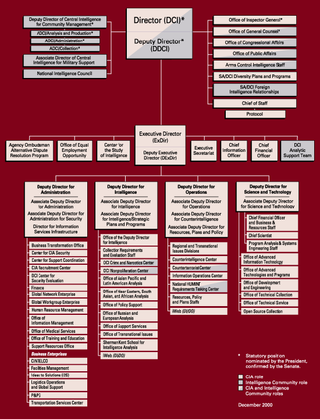

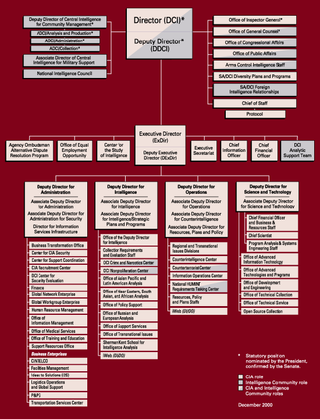

The CIA publishes organizational charts of its agency. Here are a few examples.

The Boren-McCurdy intelligence reform proposals were two legislative proposals from Senator David Boren and Representative Dave McCurdy in 1992. Both pieces of legislation proposed the creation of a National Intelligence Director. Neither bill passed into law.

The Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015 is a bill that authorizes different intelligence agencies and their activities in fiscal years 2014 and 2015. The total spending authorized by the bill is classified, but estimates based on intelligence leaks made by Edward Snowden indicate that the budget could be approximately $50 billion.

The Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014 is a U.S. public law that authorizes appropriations for fiscal year 2014 for intelligence activities of the U.S. government. The law authorizes there to be funding for intelligence agencies such as the Central Intelligence Agency or the National Security Agency, but a separate appropriations bill would also have to pass in order for those agencies to receive any money.

The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) dates from September 18, 1947, when President Harry S. Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947 into law. A major impetus that has been cited over the years for the creation of the CIA was the unforeseen attack on Pearl Harbor, but whatever Pearl Harbor's role, at the close of World War II government circles identified a need for a group to coordinate government intelligence efforts, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the State Department, the War Department, and even the Post Office were all jockeying for that new power.

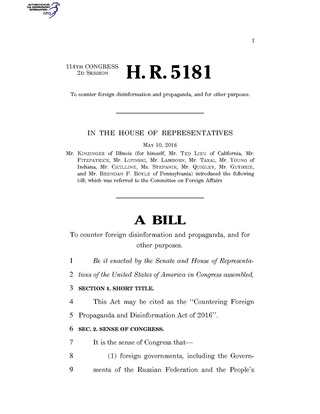

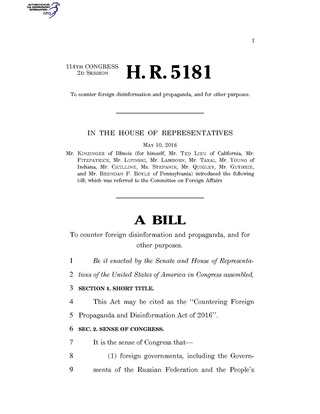

Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act is a bipartisan bill that was introduced by the United States Congress on 10 May 2016. The bill was initially called the Countering Information Warfare Act.