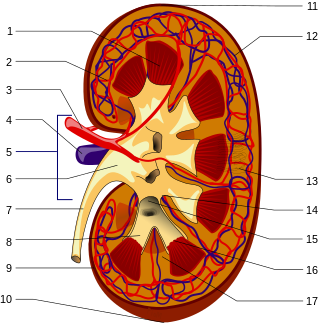

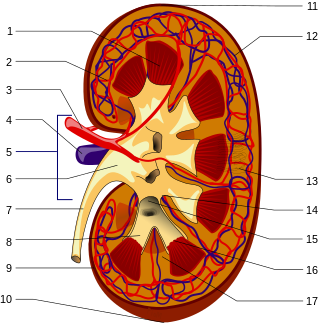

Nephrology is a specialty for both adult internal medicine and pediatric medicine that concerns the study of the kidneys, specifically normal kidney function and kidney disease, the preservation of kidney health, and the treatment of kidney disease, from diet and medication to renal replacement therapy. The word "renal" is an adjective meaning "relating to the kidneys", and its roots are French or late Latin. Whereas according to some opinions, "renal" and "nephro" should be replaced with "kidney" in scientific writings such as "kidney medicine" or "kidney replacement therapy", other experts have advocated preserving the use of renal and nephro as appropriate including in "nephrology" and "renal replacement therapy", respectively.

Proteinuria is the presence of excess proteins in the urine. In healthy persons, urine contains very little protein, less than 150 mg/day; an excess is suggestive of illness. Excess protein in the urine often causes the urine to become foamy. Severe proteinuria can cause nephrotic syndrome in which there is worsening swelling of the body.

Kidney failure, also known as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney failure is classified as either acute kidney failure, which develops rapidly and may resolve; and chronic kidney failure, which develops slowly and can often be irreversible. Symptoms may include leg swelling, feeling tired, vomiting, loss of appetite, and confusion. Complications of acute and chronic failure include uremia, hyperkalemia, and volume overload. Complications of chronic failure also include heart disease, high blood pressure, and anaemia.

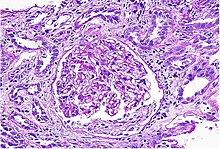

Nephritis is inflammation of the kidneys and may involve the glomeruli, tubules, or interstitial tissue surrounding the glomeruli and tubules. It is one of several different types of nephropathy.

Kidney disease, or renal disease, technically referred to as nephropathy, is damage to or disease of a kidney. Nephritis is an inflammatory kidney disease and has several types according to the location of the inflammation. Inflammation can be diagnosed by blood tests. Nephrosis is non-inflammatory kidney disease. Nephritis and nephrosis can give rise to nephritic syndrome and nephrotic syndrome respectively. Kidney disease usually causes a loss of kidney function to some degree and can result in kidney failure, the complete loss of kidney function. Kidney failure is known as the end-stage of kidney disease, where dialysis or a kidney transplant is the only treatment option.

Acute kidney injury (AKI), previously called acute renal failure (ARF), is a sudden decrease in kidney function that develops within 7 days, as shown by an increase in serum creatinine or a decrease in urine output, or both.

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), also known as Berger's disease, or synpharyngitic glomerulonephritis, is a disease of the kidney and the immune system; specifically it is a form of glomerulonephritis or an inflammation of the glomeruli of the kidney. Aggressive Berger's disease can attack other major organs, such as the liver, skin and heart.

Cystinuria is an inherited autosomal recessive disease characterized by high concentrations of the amino acid cystine in the urine, leading to the formation of cystine stones in the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. It is a type of aminoaciduria. "Cystine", not "cysteine," is implicated in this disease; the former is a dimer of the latter.

Pyelonephritis is inflammation of the kidney, typically due to a bacterial infection. Symptoms most often include fever and flank tenderness. Other symptoms may include nausea, burning with urination, and frequent urination. Complications may include pus around the kidney, sepsis, or kidney failure.

Bartter syndrome (BS) is a rare inherited disease characterised by a defect in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, which results in low potassium levels (hypokalemia), increased blood pH (alkalosis), and normal to low blood pressure. There are two types of Bartter syndrome: neonatal and classic. A closely associated disorder, Gitelman syndrome, is milder than both subtypes of Bartter syndrome.

Phosphate nephropathy or nephrocalcinosis is an adverse renal condition that arises with a formation of phosphate crystals within the kidney's tubules. This renal insufficiency is associated with the use of oral sodium phosphate (OSP) such as C.B. Fleet's Phospho soda and Salix's Visocol, for bowel cleansing prior to a colonoscopy.

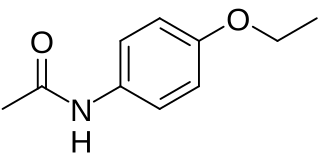

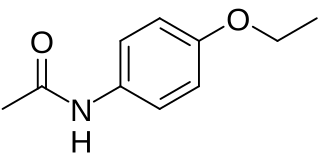

Analgesic nephropathy is injury to the kidneys caused by analgesic medications such as aspirin, bucetin, phenacetin, and paracetamol. The term usually refers to damage induced by excessive use of combinations of these medications, especially combinations that include phenacetin. It may also be used to describe kidney injury from any single analgesic medication.

Specific gravity, in the context of clinical pathology, is a urinalysis parameter commonly used in the evaluation of kidney function and can aid in the diagnosis of various renal diseases.

Nephrocalcinosis, once known as Albright's calcinosis after Fuller Albright, is a term originally used to describe the deposition of poorly soluble calcium salts in the renal parenchyma due to hyperparathyroidism. The term nephrocalcinosis is used to describe the deposition of both calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate. It may cause acute kidney injury. It is now more commonly used to describe diffuse, fine, renal parenchymal calcification in radiology. It is caused by multiple different conditions and is determined by progressive kidney dysfunction. These outlines eventually come together to form a dense mass. During its early stages, nephrocalcinosis is visible on x-ray, and appears as a fine granular mottling over the renal outlines. It is most commonly seen as an incidental finding with medullary sponge kidney on an abdominal x-ray. It may be severe enough to cause renal tubular acidosis or even end stage kidney disease, due to disruption of the kidney tissue by the deposited calcium salts.

Primary hyperoxaluria is a rare condition, resulting in increased excretion of oxalate, with oxalate stones being common.

Cholesterol embolism occurs when cholesterol is released, usually from an atherosclerotic plaque, and travels as an embolus in the bloodstream to lodge causing an obstruction in blood vessels further away. Most commonly this causes skin symptoms, gangrene of the extremities and sometimes kidney failure; problems with other organs may arise, depending on the site at which the cholesterol crystals enter the bloodstream. When the kidneys are involved, the disease is referred to as atheroembolic renal disease. The diagnosis usually involves biopsy from an affected organ. Cholesterol embolism is treated by removing the cause and giving supportive therapy; statin drugs have been found to improve the prognosis.

Urologic diseases or conditions include urinary tract infections, kidney stones, bladder control problems, and prostate problems, among others. Some urologic conditions do not affect a person for that long and some are lifetime conditions. Kidney diseases are normally investigated and treated by nephrologists, while the specialty of urology deals with problems in the other organs. Gynecologists may deal with problems of incontinence in women.

Glomerulonephrosis is a non-inflammatory disease of the kidney (nephrosis) presenting primarily in the glomerulus as nephrotic syndrome. The nephron is the functional unit of the kidney and it contains the glomerulus, which acts as a filter for blood to retain proteins and blood lipids. Damage to these filtration units results in important blood contents being released as waste in urine. This disease can be characterized by symptoms such as fatigue, swelling, and foamy urine, and can lead to chronic kidney disease and ultimately end-stage renal disease, as well as cardiovascular diseases. Glomerulonephrosis can present as either primary glomerulonephrosis or secondary glomerulonephrosis.

Distal renal tubular acidosis (dRTA) is the classical form of RTA, being the first described. Distal RTA is characterized by a failure of acid secretion by the alpha intercalated cells of the distal tubule and cortical collecting duct of the distal nephron. This failure of acid secretion may be due to a number of causes. It leads to relatively alkaline urine, due to the kidney's inability to acidify the urine to a pH of less than 5.3.

Malarial nephropathy is kidney failure attributed to malarial infection. Among various complications due to infection, renal-related disorders are often the most life-threatening. Including malaria-induced renal lesions, infection may lead to both tubulointerstitial damage and glomerulonephritis. In addition, malarial acute kidney failure has emerged as a serious problem due to its high mortality rate in non-immune adult patients.