Denominations

Sunnism

Sunni Islam is practiced by 53.4% of Oman's Muslim population. [6] [7] The Sunni communities in Oman are predominantly located south of the Al-Hajar mountain chain and in certain coastal areas. These regions have largely retained their Sunni practices from the time of Amr ibn al-As. Sunni Islam in Oman includes various schools of thought, with the Shafi'i school being particularly prominent in the southern region of Al Wusta & Dhofar, while the Hanbali school of thought is more prominent in the northern areas. The increase in the Sunni Muslim population is also helped by migrants from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Despite covering a large geographical area, the number of Omani Sunnis is relatively few compared to the Ibadis.

Ibadism

Introduction to Oman

Ibadism, named after its founder Abdallah ibn Ibad, a major head of the Khawarij, [8] traces its roots back to the early Kharijite movement. This sect emerged after the Battle of Siffin in 657 CE. [9] Arriving in Oman around 700 CE, the Ibadis were initially part of the Kharijite group but gradually distinguished themselves by adopting more moderate views compared to other Kharijite factions. [10]

Settlement and Expansion in Oman

After the death of Abdallah ibn Ibad of Banu Tamim in 700 CE, [8] the Ibadis scattered, with some settling in Oman and others in parts of the Maghreb al-Arabi (Northwest Africa). [11] In Oman, they found a conducive environment for their beliefs among the local tribes who were receptive to their message of piety and egalitarianism. By 750 CE, the Ibadis established their first state in Oman, although it was short-lived and fell to the Abbasid Caliphate in 752 CE. [12] [13]

Despite this setback, the Ibadis continued to grow in influence by forming alliances with local tribes and promoting the idea that they were the true representatives of the Omani people, in contrast to the Abbasids who they deemed as foreign oppressors. In 793 CE, another Ibadi state emerged in Oman, lasting until the Abbasid recapture in 893 CE. Even after the Abbasid reconquests, Ibadi imams maintained considerable power and influence in the region. Over subsequent centuries, Ibadism became deeply entrenched in Omani society, leading to the re-establishment of Ibadi imamates in the late modern period. [14] [15]

How Ibadis Became the Ruling Sect

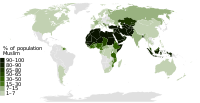

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

The Ibadis managed to become the ruling sect in Oman despite not being the majority initially due to their strong organizational structure and ability to mobilize the local tribes. [16] They skillfully portrayed the Abbasids as foreign oppressors and themselves as the indigenous defenders of Omani identity and autonomy. This narrative resonated with many Omanis, allowing the Ibadis to gain significant support. Over time, they established a series of imamate systems, where the imam held both religious and political authority. [17] However, the persistent power of the Ibadi imamate was challenged in the mid-20th century. The conflict culminated in the Jebel Akhdar War (1954-1959), where the Sultanate of Muscat, aided by British forces, fought against the Ibadi imamate. [18] The war ended with the defeat of the imamate and solidified the Sultanate's control over the entire country. This victory marked the end of the Ibadi imamate as a political entity and paved the way for the current Omani monarchy, which emerged from these historical roots. [19]

Modern Ibadi Reform under the Sultanate

Under the current Omani sultanate, Ibadism has undergone significant reforms to adapt to the changing political and social landscape. The establishment of the Sultanate of Oman in the mid-18th century marked a pivotal shift from the traditional Ibadi imamate system to a hereditary monarchy. This transition was significantly influenced by internal conflicts and external support, particularly from the British. [20]

The reforms done under Ahmed bin Hamad al-Khalili, the Ibadi's Grand Mufti, have been crucial in shaping contemporary Ibadi practice. Al-Khalili endorsed the hereditary monarchy, moving away from the traditional election of imams based on merit and piety. This shift was part of broader efforts to modernize the state and integrate Ibadism within the framework of a modern nation-state.

Religious tolerance has been another hallmark of these reforms. The Sultanate promotes an inclusive approach, allowing various religious communities to practice their faith openly. This approach contrasts with the historical Ibadi practice of Bara'ah, which involved disassociating from those considered sinful or deviant, including some companions of the Prophet Muhammad, particularly Uthman ibn Affan and Ali ibn Abi Talib. Under al-Khalili's influence, there has been a softening of these views, fostering a more inclusive religious environment in Oman. Historically, Ibadi texts have criticized and denounced these figures. [21] [22] [23] However, under al-Khalili's influence, there has been a significant softening of these views, fostering a more inclusive religious environment in Oman. This reform has helped bridge the divide between different Muslim sects and other religious communities, promoting a sense of unity and coexistence within the country.

Differences from mainstream Islam (Sunni)

Theological Foundations

- Election of imams: Unlike Sunni Islam, which accepts dynastic succession and hereditary leadership in some cases, Ibadis traditionally believe in electing imams based on merit and piety. [25] However, the current Ibadi leadership in Oman has adopted a hereditary monarchy system. [26]

- Views on leadership: Ibadis reject the Sunni notion of a hereditary caliphate, emphasizing the election of leaders through a consultative process. This principle has shifted in contemporary Oman under the monarchy.

Religious Practices

- Interpretation of divine attributes: Unlike Sunnis, who believe that God's attributes are unique but real, Ibadis and Mu'tazilites deny the literal existence of these attributes.

- Created nature of the Quran: Ibadis believe that God's speech is created, contrasting with the Sunni belief in the uncreated nature of God's speech.

Social and Ethical Principles

- Walayah and Bara'ah: Ibadis adhere to the principles of Walayah (affiliation) and Bara'ah (disassociation), dictating social and religious interactions. This includes disassociating from those deemed sinful or deviant, a practice not emphasized in Sunni Islam.

- Kufr al-Ni'mah (disbelievers of grace): Ibadis classify major sinners as "Kufr al-Ni'mah," or disbelievers of grace. This means that while such individuals are considered Muslims and retain their rights as fellow Muslims, they are believed to be eternally condemned to hell in the hereafter albeit they do not repent prior to their death.

Eschatological Views

- Seeing God in the afterlife: Ibadis deny seeing of God in the afterlife, a belief shared with the Shia but differing from the Sunni perspective.

- Interpretation of Judgment Day concepts: Ibadis interpret the concepts of the Scale of Deeds (Meezaan) and the Bridge (Siraat) on the Day of Judgment metaphorically rather than literally.

These differences highlight the unique characteristics of Ibadism compared to Sunni Islam, shaping the religious and social landscape of Oman.

Shi'ism

Shi'ism constitutes a minority within the Omani Muslim population, predominantly following the Twelver branch. Shiite communities are mainly located along the Al Batinah coast and in Muscat. Al-Lawatia, a prominent Shiite tribe, have Persian origins and have been significant in trade and commerce. Despite their minority status, they practice their faith openly, celebrating events like Ashura. The Omani government's policy of religious tolerance has fostered coexistence and inclusion, allowing Shiites to contribute significantly to Oman's cultural and economic development.