This article needs additional citations for verification .(September 2017) |

Iteration marks are characters or punctuation marks that represent a duplicated character or word.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(September 2017) |

Iteration marks are characters or punctuation marks that represent a duplicated character or word.

In Chinese, 𠄠 or U+16FE3𖿣OLD CHINESE ITERATION MARK (usually appearing as 〻, equivalent to the modern ideograph 二) or 々 is used in casual writing to represent a doubled character. However, it is not used in formal writing anymore, and it never appeared in printed matter.[ citation needed ] In a tabulated table or list, vertical repetition can be represented by a ditto mark (〃).

Iteration marks have been occasionally used for more than two thousand years in China. The example image shows an inscription in bronze script, a variety of formal writing dating to the Zhou Dynasty, that ends with "子𠄠孫𠄠寶用", where the small 𠄠 ("two") is used as iteration marks in the phrase "子子孫孫寶用" ("descendants to use and to treasure").

In Filipino, Indonesian, and Malay, words that are repeated can be shortened with the use of numeral "2". For example, the Malay kata-kata ("words", from single kata) can be shortened to kata2, and jalan-jalan ("to walk around", from single jalan) can be shortened to jalan2. The usage of "2" can be also replaced with superscript "2" (e.g. kata2 for kata2). The sign may also be used for reduplicated compound words with slight sound changes, for example hingar2 for hingar-bingar ("commotion"). Suffixes may be added after "2", for example in the word kebarat2an ("Western in nature", from the basic word barat ("West") with the prefix ke- and suffix -an). [1]

The use of this mark dates back to the time when these languages were written with Arabic script, specifically the Jawi or Pegon varieties. Using the Arabic numeral ٢, words such as رام رام (rama-rama, butterfly) can be shortened to رام٢. The use of Arabic numeral ٢ was also adapted to several Brahmi derived scripts of the Malay archipelago, notably Javanese, [2] Sundanese, [2] Lontara, [3] and Makassaran. [4] As the Latin alphabet was introduced to the region, the Western-style Arabic numeral "2" came to be use for Latin-based orthography.

The use of "2" as an iteration mark was official in Indonesia up to 1972, as part of the Republican Spelling System. Its usage was discouraged when the Enhanced Indonesian Spelling System was adopted, and even though it commonly found in handwriting or old signage, it is considered to be inappropriate for formal writing and documents. [1]

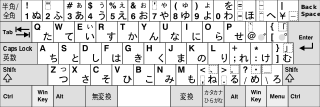

Japanese has various iteration marks for its three writing systems, namely kanji, hiragana, and katakana, but only the (horizontal) kanji iteration mark (々) is commonly used today.[ citation needed ]

In Japanese, iteration marks called odoriji (踊り字, "dancing mark"), kasaneji (重ね字), kurikaeshikigō (繰り返し記号), or hanpukukigō (反復記号, "repetition symbols") are used to represent a duplicated character representing the same morpheme. For example, hitobito, "people", is usually written 人々, using the kanji for 人 with an iteration mark, 々, rather than 人人, using the same kanji twice. The use of two kanji in place of an iteration mark is allowed, and in simple cases may be used due to being easier to write.

In contrast, while hibi (日々, "daily, day after day") is written with the iteration mark, as the morpheme is duplicated, hinichi (日日, "number of days, date") is written with the character duplicated, because it represents different morphemes (hi and nichi). Further, while hibi can in principle be written (confusingly) as 日日, hinichi cannot be written as 日々, since that would imply repetition of the sound as well as the character. In potentially confusing examples such as this, readings can be disambiguated by writing words out in hiragana, so hinichi is often found as 日にち or even ひにち rather than 日日.

Sound changes can occur in duplication, which is not reflected in writing; examples include hito (人) and hito (人) being pronounced hitobito (人々) ( rendaku ) or koku (刻) and koku (刻) being pronounced kokkoku (刻々) (gemination), though this is also pronounced kokukoku.

![[?]

, an iteration mark (derived from

) used only in vertical writing. Vertical ideographic iteration mark.png](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Vertical_ideographic_iteration_mark.png/70px-Vertical_ideographic_iteration_mark.png)

The formal name of the kanji repetition symbol (々) is dōnojiten (同の字点) but is sometimes called noma (のま) because it looks like the katakana no (ノ) and ma (マ). This symbol originates from a simplified form of the character 仝 , a variant of "same" ( 同 ) written in the grass script style. [5]

Although Japanese kanji iteration marks are borrowed from Chinese, the grammatical function of duplication differs, as do the conventions on the use of these characters.

While Japanese does not have a grammatical plural form per se, some kanji can be reduplicated to indicate plurality (as a collective noun, not many individuals). This differs from Chinese, which normally repeats characters only for the purposes of adding emphasis, although there are some exceptions (e.g., 人, rén, "person"; 人人, rénrén, "everybody").

However, for some words duplication may alter the meaning:

Using 々 instead of repeating kanji is usually the preferred form, with two restrictions:

When the reading is different, the second kanji is often simply written out to avoid confusion. Examples of such include:

The repetition mark is not used in every case where two identical characters appear side by side, but only where the repetition itself is etymologically significant—when the repetition is part of a single word. Where a character ends up appearing twice as part of a compound, it is usually written out in full:

Similarly, in certain Chinese borrowings, it is generally preferred to write out both characters, as in 九九 (ku-ku Chinese multiplication table) or 担担麺 (tan-tan-men dan dan noodles), though in practice 々 is often used.

In vertical writing, the character 〻 (Unicode U+303B), a cursive derivative of 𠄠 ("two", as in Chinese, above), can be employed instead, although this is increasingly rare.

Kana uses different iteration marks; one for hiragana, ゝ, and one for katakana, ヽ. The hiragana iteration mark is seen in some personal names like さゝきSasaki or おゝのŌno, and it forms part of the formal name of the car company Isuzu (いすゞ).

Unlike the kanji iteration marks, which do not reflect sound changes, kana iteration marks closely reflect sound, and the kana iteration marks can be combined with the dakuten voicing mark to indicate that the repeated syllable should be voiced, for example みすゞMisuzu. If the first syllable is already voiced, for example じじjiji, the voiced repetition mark still needs to be used: じゞ rather than じゝ, which would be read as jishi.

While widespread in old Japanese texts, the kana iteration marks are generally not used in modern Japanese outside proper names, though they may appear in informal handwritten texts.

![A variety of iteration marks in use in the classical text Tsurezuregusa (Tu Ran Cao

) [Shi niYu riChuan huruShi -genigenishikuSuo "uchiobomeki-mataYi hiChao rubekarazu]

(73rd passage) IterationMarks600.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b5/IterationMarks600.jpg/220px-IterationMarks600.jpg)

In addition to the single-character iteration marks, there are also two-character-sized repeat marks, which are used to repeat two or more characters. They are used in vertical writing only, and they are effectively obsolete in modern Japanese. The vertical kana repeat marks 〱 (unvoiced) and 〲 (voiced) resemble the hiragana character ku (く), giving them their name, kunojiten (くの字点). They stretch to fill the space typically occupied by two characters, but may indicate a repetition of more than two characters—they indicate that the preceding word or phrase be repeated. For example, the duplicated phrase 何とした何とした may be repeated as 何とした〱—note that here it repeats four characters. If a dakuten (voiced mark) is added, it applies to the first sound of the repeated word; this is written as 〲. For example, tokorodokoro could be written horizontally as ところ〲; the voiced iteration mark only applies to the first sound と.

In addition to the single-character representations U+3031〱VERTICAL KANA REPEAT MARK and U+3032〲VERTICAL KANA REPEAT WITH VOICED SOUND MARK, Unicode provides the half-character versions U+3033〳VERTICAL KANA REPEAT MARK UPPER HALF, U+3034〴VERTICAL KANA REPEAT WITH VOICED SOUND MARK UPPER HALF and U+3035〵VERTICAL KANA REPEAT MARK LOWER HALF, which can be stacked to render both voiced and unvoiced repeat marks:

〳 〵 | 〴 〵 |

As support for these is limited, the ordinary forward slash / and backward slash \ are occasionally used as substitutes.

Alternatively, multiple single-character iteration marks can be used, as in tokorodokoro (ところゞゝゝ) or bakabakashii (馬鹿々々しい). This practice is also uncommon in modern writing, though it is occasionally seen in horizontal writing as a substitute for the vertical repeat mark.

Unlike the single-kana iteration mark, if the first kana is voiced, the unvoiced version 〱 alone will repeat the voiced sound.

Further, if okurigana is present, then no iteration mark should be used, as in 休み休み. This is prescribed by the Japanese Ministry of Education in its 1981 Cabinet notification prescribes, rule #6.[ citation needed ]

In the Nuosu language, ꀕ is used to represent a doubled sound, for example ꈀꎭꀕ, kax sha sha. It is used in all forms of writing.

In Tangut manuscripts the sign 𖿠 is sometimes used to represent a doubled character; this sign does not occur in printed texts. In Unicode this character is U+16FE0TANGUT ITERATION MARK, in the Ideographic Symbols and Punctuation block.

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the signs:

— zp(wj) sn(wj) , literally meaning "two times", repeat the previous sign or word.

In Khmer, leiktō ( ៗ ) as for Thai, mai yamok ( ๆ ) and Lao, ko la ( ໆ ) represent a repeated syllable where as it besides the word. This used to be written as numeral two (២) and the form changed over time. A repeated word could be used either, to demonstrate plurality, to emphasize or to soften the meaning of the original word.

In English, Spanish, French, Italian, German, Portuguese, Czech, Polish and Turkish lists, the ditto mark (″) represents a word repeated from the equivalent position in the line above it; or an evenly-spaced row of ditto marks represents any number of words repeated from above. For example:

This is common in handwriting and formerly in typewritten texts.

In Unicode, the ditto mark of Western languages has been defined to be equivalent to the U+2033″ DOUBLE PRIME (″).[ citation needed ] The separate character U+3003〃DITTO MARK is to be used in the CJK scripts only. [6] [7] [8]

The convention in Polish handwriting, Czech, Swedish, and Austrian German is to use a ditto mark on the baseline together with horizontal lines spanning the extent of the word repeated, for example:

Furigana is a Japanese reading aid consisting of smaller kana printed either above or next to kanji or other characters to indicate their pronunciation. It is one type of ruby text. Furigana is also known as yomigana (読み仮名) and rubi in Japanese. In modern Japanese, it is usually used to gloss rare kanji, to clarify rare, nonstandard or ambiguous kanji readings, or in children's or learners' materials. Before the post-World War II script reforms, it was more widespread.

Hiragana is a Japanese syllabary, part of the Japanese writing system, along with katakana as well as kanji.

Katakana is a Japanese syllabary, one component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana, kanji and in some cases the Latin script.

Kana are syllabaries used to write Japanese phonological units, morae. Such syllabaries include (1) the original kana, or magana, which were Chinese characters (kanji) used phonetically to transcribe Japanese, the most prominent magana system being man'yōgana (万葉仮名); the two descendants of man'yōgana, (2) hiragana, and (3) katakana. There are also hentaigana, which are historical variants of the now-standard hiragana. In current usage, 'kana' can simply mean hiragana and katakana.

Kanji are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese script used in the writing of Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese and are still used, along with the subsequently-derived syllabic scripts of hiragana and katakana. The characters have Japanese pronunciations; most have two, with one based on the Chinese sound. A few characters were invented in Japan by constructing character components derived from other Chinese characters. After the Meiji Restoration, Japan made its own efforts to simplify the characters, now known as shinjitai, by a process similar to China's simplification efforts, with the intention to increase literacy among the common folk. Since the 1920s, the Japanese government has published character lists periodically to help direct the education of its citizenry through the myriad Chinese characters that exist. There are nearly 3,000 kanji used in Japanese names and in common communication.

In relation to the Japanese language and computers many adaptation issues arise, some unique to Japanese and others common to languages which have a very large number of characters. The number of characters needed in order to write in English is quite small, and thus it is possible to use only one byte (28=256 possible values) to encode each English character. However, the number of characters in Japanese is many more than 256 and thus cannot be encoded using a single byte - Japanese is thus encoded using two or more bytes, in a so-called "double byte" or "multi-byte" encoding. Problems that arise relate to transliteration and romanization, character encoding, and input of Japanese text.

In the Japanese writing system, hentaigana are variant forms of hiragana.

The dakuten, colloquially ten-ten, is a diacritic most often used in the Japanese kana syllabaries to indicate that the consonant of a syllable should be pronounced voiced, for instance, on sounds that have undergone rendaku.

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated currently in use.

The classical Japanese language, also called "old writing", sometimes simply called "Medieval Japanese" is the literary form of the Japanese language that was the standard until the early Shōwa period (1926–1989). It is based on Early Middle Japanese, the language as spoken during the Heian period (794–1185), but exhibits some later influences. Its use started to decline during the late Meiji period (1868–1912) when novelists started writing their works in the spoken form. Eventually, the spoken style came into widespread use, including in major newspapers, but many official documents were still written in the old style. After the end of World War II, most documents switched to the spoken style, although the classical style continues to be used in traditional genres, such as haiku and waka. Old laws are also left in the classical style unless fully revised.

Gyaru-moji or heta-moji is a style of obfuscated (cant) Japanese writing popular amongst urban Japanese youth. As the name gyaru-moji suggests, this writing system was created by and remains primarily employed by young women.

Mojikyō, also known by its full name Konjaku Mojikyō, is a character encoding scheme. The Mojikyō Institute, which published the character set, also published computer software and TrueType fonts to accompany it. The Mojikyō Institute, chaired by Tadahisa Ishikawa (石川忠久), originally had its character set and related software and data redistributed on CD-ROMs sold in Kinokuniya stores.

The chōonpu, also known as chōonkigō (長音記号), onbiki (音引き), bōbiki (棒引き), or Katakana-Hiragana Prolonged Sound Mark by the Unicode Consortium, is a Japanese symbol that indicates a chōon, or a long vowel of two morae in length. Its form is a horizontal or vertical line in the center of the text with the width of one kanji or kana character. It is written horizontally in horizontal text and vertically in vertical text. The chōonpu is usually used to indicate a long vowel sound in katakana writing, rarely in hiragana writing, and never in romanized Japanese. The chōonpu is a distinct mark from the dash, and in most Japanese typefaces it can easily be distinguished. In horizontal writing it is similar in appearance to, but should not be confused with, the kanji character 一 ("one").

In Japanese language, Ryakuji are colloquial simplifications of kanji.

Wi is a nearly obsolete Japanese kana. The combination of a W-column kana letter with ゐ゙ in hiragana was introduced to represent [vi] in the 19th century and 20th century. It is presumed that 'ゐ' represented, and that 'ゐ' and 'い' represented distinct pronunciations before merging to sometime between the Kamakura and Taishō periods. Along with the kana for we, this kana was deemed obsolete in Japanese with the orthographic reforms of 1946, to be replaced by 'い/イ' in all contexts. It is now rare in everyday usage; in onomatopoeia and foreign words, the katakana form 'ウィ' (U-[small-i]) is preferred.

The ditto mark is a shorthand sign, used mostly in hand-written text, indicating that the words or figures above it are to be repeated.

The Japanese script reform is the attempt to correlate standard spoken Japanese with the written word, which began during the Meiji period. This issue is known in Japan as the kokugo kokuji mondai. The reforms led to the development of the modern Japanese written language, and explain the arguments for official policies used to determine the usage and teaching of kanji rarely used in Japan.

JIS X 0208 is a 2-byte character set specified as a Japanese Industrial Standard, containing 6879 graphic characters suitable for writing text, place names, personal names, and so forth in the Japanese language. The official title of the current standard is 7-bit and 8-bit double byte coded KANJI sets for information interchange. It was originally established as JIS C 6226 in 1978, and has been revised in 1983, 1990, and 1997. It is also called Code page 952 by IBM. The 1978 version is also called Code page 955 by IBM.

The romanization of Japanese is the use of Latin script to write the Japanese language. This method of writing is sometimes referred to in Japanese as rōmaji.

Braille Kanji is a system of braille for transcribing written Japanese. It was devised in 1969 by Tai'ichi Kawakami, a teacher at the Osaka School for the Blind, and was still being revised in 1991. It supplements Japanese Braille by providing a means of directly encoding kanji characters without having to first convert them to kana. It uses an 8-dot braille cell, with the lower six dots corresponding to the cells of standard Japanese Braille, and the upper two dots indicating the constituent parts of the kanji. The upper dots are numbered 0 and 7, the opposite convention of 8-dot braille in Western countries, where the extra dots are added to the bottom of the cell. A kanji will be transcribed by anywhere from one to three braille cells.