In physics, specifically statistical mechanics, a population inversion occurs while a system exists in a state in which more members of the system are in higher, excited states than in lower, unexcited energy states. It is called an "inversion" because in many familiar and commonly encountered physical systems, this is not possible. This concept is of fundamental importance in laser science because the production of a population inversion is a necessary step in the workings of a standard laser.

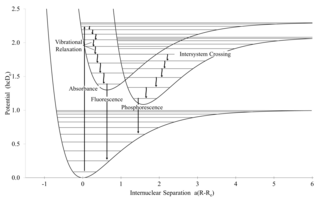

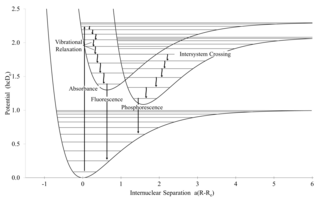

Spontaneous emission is the process in which a quantum mechanical system transits from an excited energy state to a lower energy state and emits a quantized amount of energy in the form of a photon. Spontaneous emission is ultimately responsible for most of the light we see all around us; it is so ubiquitous that there are many names given to what is essentially the same process. If atoms are excited by some means other than heating, the spontaneous emission is called luminescence. For example, fireflies are luminescent. And there are different forms of luminescence depending on how excited atoms are produced. If the excitation is effected by the absorption of radiation the spontaneous emission is called fluorescence. Sometimes molecules have a metastable level and continue to fluoresce long after the exciting radiation is turned off; this is called phosphorescence. Figurines that glow in the dark are phosphorescent. Lasers start via spontaneous emission, then during continuous operation work by stimulated emission.

A quantum mechanical system or particle that is bound—that is, confined spatially—can only take on certain discrete values of energy, called energy levels. This contrasts with classical particles, which can have any amount of energy. The term is commonly used for the energy levels of the electrons in atoms, ions, or molecules, which are bound by the electric field of the nucleus, but can also refer to energy levels of nuclei or vibrational or rotational energy levels in molecules. The energy spectrum of a system with such discrete energy levels is said to be quantized.

Photoluminescence is light emission from any form of matter after the absorption of photons. It is one of many forms of luminescence and is initiated by photoexcitation, hence the prefix photo-. Following excitation, various relaxation processes typically occur in which other photons are re-radiated. Time periods between absorption and emission may vary: ranging from short femtosecond-regime for emission involving free-carrier plasma in inorganic semiconductors up to milliseconds for phosphoresence processes in molecular systems; and under special circumstances delay of emission may even span to minutes or hours.

Phosphorescence is a type of photoluminescence related to fluorescence. When exposed to light (radiation) of a shorter wavelength, a phosphorescent substance will glow, absorbing the light and reemitting it at a longer wavelength. Unlike fluorescence, a phosphorescent material does not immediately reemit the radiation it absorbs. Instead, a phosphorescent material absorbs some of the radiation energy and reemits it for a much longer time after the radiation source is removed.

Photochemistry is the branch of chemistry concerned with the chemical effects of light. Generally, this term is used to describe a chemical reaction caused by absorption of ultraviolet, visible light (400–750 nm) or infrared radiation (750–2500 nm).

Electron excitation is the transfer of a bound electron to a more energetic, but still bound state. This can be done by photoexcitation (PE), where the electron absorbs a photon and gains all its energy or by collisional excitation (CE), where the electron receives energy from a collision with another, energetic electron. Within a semiconductor crystal lattice, thermal excitation is a process where lattice vibrations provide enough energy to transfer electrons to a higher energy band such as a more energetic sublevel or energy level. When an excited electron falls back to a state of lower energy, it undergoes electron relaxation (deexcitation). This is accompanied by the emission of a photon or by a transfer of energy to another particle. The energy released is equal to the difference in energy levels between the electron energy states.

Intersystem crossing (ISC) is an isoenergetic radiationless process involving a transition between the two electronic states with different spin multiplicity.

Stokes shift is the difference between positions of the band maxima of the absorption and emission spectra of the same electronic transition. It is named after Irish physicist George Gabriel Stokes. Sometimes Stokes shifts are given in wavelength units, but this is less meaningful than energy, wavenumber or frequency units because it depends on the absorption wavelength. For instance, a 50 nm Stokes shift from absorption at 300 nm is larger in terms of energy than a 50 nm Stokes shift from absorption at 600 nm.

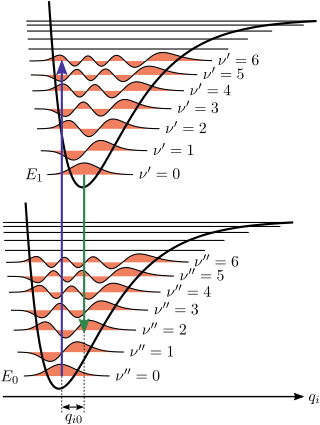

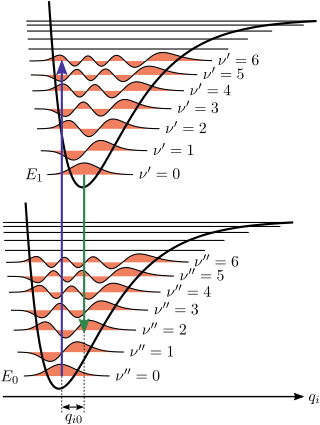

The Franck–Condon principle is a rule in spectroscopy and quantum chemistry that explains the intensity of vibronic transitions. The principle states that during an electronic transition, a change from one vibrational energy level to another will be more likely to happen if the two vibrational wave functions overlap more significantly.

Internal conversion is a transition from a higher to a lower electronic state in a molecule or atom. It is sometimes called "radiationless de-excitation", because no photons are emitted. It differs from intersystem crossing in that, while both are radiationless methods of de-excitation, the molecular spin state for internal conversion remains the same, whereas it changes for intersystem crossing. The energy of the electronically excited state is given off to vibrational modes of the molecule. The excitation energy is transformed into heat.

Photosensitizers are light absorbers that alter the course of a photochemical reaction. They usually are catalysts. They can function by many mechanisms, sometimes they donate an electron to the substrate, sometimes they abstract a hydrogen atom from the substrate. At the end of this process, the photosensitizer returns to its ground state, where it remains chemically intact, poised to absorb more light. One branch of chemistry which frequently utilizes photosensitizers is polymer chemistry, using photosensitizers in reactions such as photopolymerization, photocrosslinking, and photodegradation. Photosensitizers are also used to generate prolonged excited electronic states in organic molecules with uses in photocatalysis, photon upconversion and photodynamic therapy. Generally, photosensitizers absorb electromagnetic radiation consisting of infrared radiation, visible light radiation, and ultraviolet radiation and transfer absorbed energy into neighboring molecules. This absorption of light is made possible by photosensitizers' large de-localized π-systems, which lowers the energy of HOMO and LUMO orbitals to promote photoexcitation. While many photosensitizers are organic or organometallic compounds, there are also examples of using semiconductor quantum dots as photosensitizers.

Mostafa A. El-Sayed is an Egyptian-American physical chemist, nanoscience researcher, member of the National Academy of Sciences and US National Medal of Science laureate. He is known for the spectroscopy rule named after him, the El-Sayed rule.

The zero-phonon line and the phonon sideband jointly constitute the line shape of individual light absorbing and emitting molecules (chromophores) embedded into a transparent solid matrix. When the host matrix contains many chromophores, each will contribute a zero-phonon line and a phonon sideband to the absorption and emission spectra. The spectra originating from a collection of identical chromophores in a matrix is said to be inhomogeneously broadened because each chromophore is surrounded by a somewhat different matrix environment which modifies the energy required for an electronic transition. In an inhomogeneous distribution of chromophores, individual zero-phonon line and phonon sideband positions are therefore shifted and overlapping.

Kasha's rule is a principle in the photochemistry of electronically excited molecules. The rule states that photon emission occurs in appreciable yield only from the lowest excited state of a given multiplicity. It is named after American spectroscopist Michael Kasha, who proposed it in 1950.

In coordination chemistry, Tanabe–Sugano diagrams are used to predict absorptions in the ultraviolet (UV), visible and infrared (IR) electromagnetic spectrum of coordination compounds. The results from a Tanabe–Sugano diagram analysis of a metal complex can also be compared to experimental spectroscopic data. They are qualitatively useful and can be used to approximate the value of 10Dq, the ligand field splitting energy. Tanabe–Sugano diagrams can be used for both high spin and low spin complexes, unlike Orgel diagrams, which apply only to high spin complexes. Tanabe–Sugano diagrams can also be used to predict the size of the ligand field necessary to cause high-spin to low-spin transitions.

Photoluminescence excitation is a specific type of photoluminescence and concerns the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter. It is used in spectroscopic measurements where the frequency of the excitation light is varied, and the luminescence is monitored at the typical emission frequency of the material being studied. Peaks in the PLE spectra often represent absorption lines of the material. PLE spectroscopy is a useful method to investigate the electronic level structure of materials with low absorption due to the superior signal-to-noise ratio of the method compared to absorption measurements.

Vibronic spectroscopy is a branch of molecular spectroscopy concerned with vibronic transitions: the simultaneous changes in electronic and vibrational energy levels of a molecule due to the absorption or emission of a photon of the appropriate energy. In the gas phase, vibronic transitions are accompanied by changes in rotational energy also.

Bond softening is an effect of reducing the strength of a chemical bond by strong laser fields. To make this effect significant, the strength of the electric field in the laser light has to be comparable with the electric field the bonding electron "feels" from the nuclei of the molecule. Such fields are typically in the range of 1–10 V/Å, which corresponds to laser intensities 1013–1015 W/cm2. Nowadays, these intensities are routinely achievable from table-top Ti:Sapphire lasers.

Thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) is a process through which a molecular species in a non-emitting excited state can incorporate surrounding thermal energy to change states and only then undergo light emission. The TADF process usually involves an excited molecular species in a triplet state, which commonly has a forbidden transition to the ground state termed phosphorescence. By absorbing nearby thermal energy the triplet state can undergo reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) converting it to a singlet state, which can then de-excite to the ground state and emit light in a process termed fluorescence. Along with fluorescent and phosphorescent compounds, TADF compounds are one of the three main light-emitting materials used in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs). Although most TADF molecules rely on the RISC from a triplet state to a singlet state, some of them take advantage of RISC processes between states with other spin multiplicities instead, for example from a quartet state to a doublet state.