Operation Fortitude was a military deception operation by the Allied nations as part of Operation Bodyguard, an overall deception strategy during the buildup to the 1944 Normandy landings. Fortitude was divided into two subplans, North and South, and had the aim of misleading the German High Command as to the location of the invasion.

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a Theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It commanded Army Ground Forces (AGF), United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), and Army Service Forces (ASF) operations north of Italy and the Mediterranean coast. It was bordered to the south by the North African Theater of Operations, United States Army (NATOUSA), which later became the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, United States Army (MTOUSA).

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force was the headquarters of the Commander of Allied forces in northwest Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. US General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the commander in SHAEF throughout its existence. The position itself shares a common lineage with Supreme Allied Commander Europe and Atlantic, but they are different titles.

Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) was the headquarters that controlled all Allied operational forces in the Mediterranean theatre of World War II from August 1942 until the end of the war in Europe in May 1945.

The Allied Expeditionary Air Force (AEAF), also known as the Allied Armies’ Expeditionary Air Force (AAEAF), was the expeditionary warfare component of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) which controlled the tactical air power of the Allied forces during Operation Overlord during World War II in 1944.

The First Allied Airborne Army was an Allied formation formed on 2 August 1944 by the order of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. The formation was part of the Allied Expeditionary Force and controlled all Allied airborne forces in Western Europe from August 1944 to May 1945. These included the U.S. IX Troop Carrier Command, the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps, which controlled the 17th, 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and a number of independent airborne units, all British airborne forces including the 1st and 6th Airborne Division plus the Polish 1st Parachute Brigade.

The Psychological Warfare Division of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force was a joint Anglo-American organization set-up in World War II tasked with conducting (predominantly) white tactical psychological warfare against German troops and recently liberated countries in Northwest Europe, during and after D-Day. It was headed by US Brigadier-General Robert A. McClure. The Division was formed from staff of the US Office of War Information (OWI) and Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and the British Political Warfare Executive (PWE).

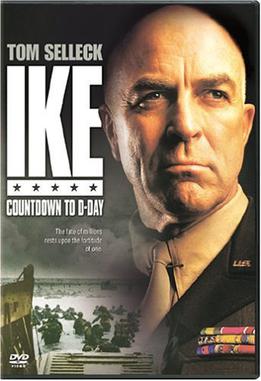

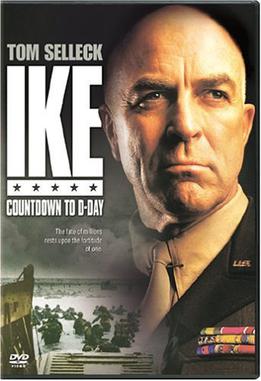

Ike: Countdown to D-Day is a 2004 American made-for-television historical war drama film originally aired on the American television channel A&E, directed by Robert Harmon and written by Lionel Chetwynd. Countdown to D-Day was filmed entirely in New Zealand with the roles of British characters played by New Zealanders; the American roles were played by Americans.

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Normandy landings. A 1,200-plane airborne assault preceded an amphibious assault involving more than 5,000 vessels. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel on 6 June, and more than two million Allied troops were in France by the end of August.

In the military, D-Day is the day on which a combat attack or operation is to be initiated. The best-known D-Day is during World War II, on June 6, 1944—the day of the Normandy landings—initiating the Western Allied effort to liberate western Europe from Nazi Germany. However, many other invasions and operations had a designated D-Day, both before and after that operation.

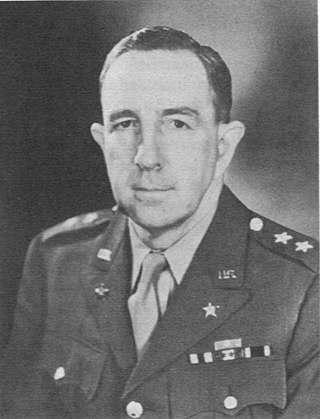

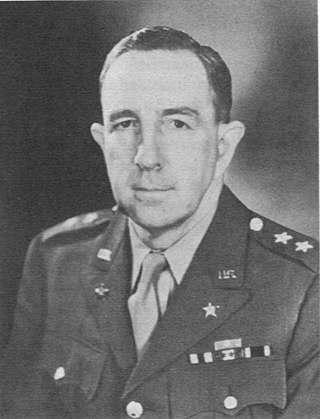

Major General Ray Wehnes Barker was a United States Army officer of the Allied Forces, and served in the European Theater of Operations during World War II. Barker was a key member of the combined United States-British group, which became known as COSSAC. This group planned the Battle of Normandy, codenamed "Operation Overlord", also known as D-Day, which liberated Nazi-occupied France. He served as the Deputy Chief of Staff of the European Theater from 1943–1944, and Deputy Chief of Staff for Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF).

Julius Cecil Holmes was a US government official who served as Ambassador to Iran.

Lieutenant General Harold Roe "Pink" Bull was a general in the United States Army and served as Assistant Chief of Staff (G-3) at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) from 1943 to 1945.

General Sir John Francis Martin Whiteley, was a senior British Army officer who became Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff (DCIGS). A career soldier, Whiteley was commissioned in 1915 into the Royal Engineers from the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. During the First World War he served in Salonika and the Middle East.

Camp Griffiss was a US military base in the United Kingdom during and after World War II. Constructed within the grounds of Bushy Park in Middlesex,, England, it served as the European Headquarters for the United States Army Air Forces from July 1942 to December 1944. From here Dwight D. Eisenhower planned the D-Day invasion. Most of the camp's huts had been removed by the early 1960s, and a memorial tablet now stands on the site.

Operation Peppermint was the codename given during World War II to preparations by the Manhattan Project and the European Theater of Operations United States Army (ETOUSA) to counter the danger that the Germans might disrupt the June 1944 Normandy landings with radioactive poisons.

Colonel Richard Ernest Dupuy was a United States Army officer and military historian.

The "People of Western Europe" speech was made by Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force General Dwight D. Eisenhower in the run-up to the invasion of Normandy in 1944. Addressed to the people of occupied Europe it informed them of the start of the invasion and advised them on the actions Eisenhower wanted them to take. It also addressed the Allies' plans for post-liberation government.

The Overlord planners for the invasion of Europe in 1944 specified suitable weather for the assault landing; with only a few days in each month suitable. In May and June 1944 frequent pre-assault meetings were held at Southwick House in Hampshire near Portsmouth by Eisenhower with Group Captain James Stagg of the RAF, the Chief Meteorological Officer, SHAEF, his deputy Colonel Donald Yates of the USAAF, and his three two-man teams of meteorologists. Stagg was a "dour but canny Scot.. " He had been given the rank of group captain in the RAF "to lend him the necessary authority in a military milieu unused to outsiders". The senior commanders were General Bernard Montgomery, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay and Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, plus Eisenhower's deputy, Air Marshall Arthur Tedder, his chief of staff Walter Bedell Smith and his deputy chief of Staff Major General Harold R. Bull.

John Ford's D-Day footage refers to the motion-picture film shot by 56 U.S. Coast Guard combat photographers and automated cameras mounted on landing craft under the direction of legendary Hollywood film director John Ford on Omaha Beach and environs during the Normandy landings and Battle of Normandy in summer 1944. Director George Stevens landed with the HMS Belfast and shot on Juno Beach. A Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) timeline reported that 344,000 ft (105,000 m) of film was processed by the Allied communications departments in June 1944.