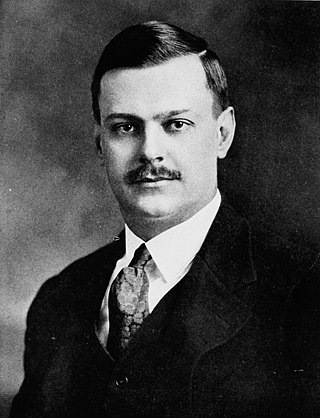

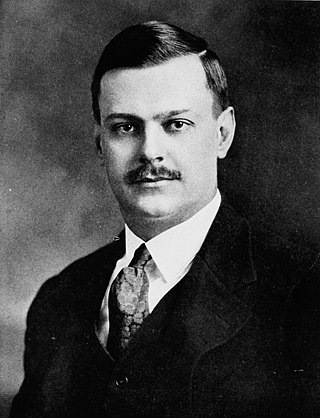

Simon Flexner was a physician, scientist, administrator, and professor of experimental pathology at the University of Pennsylvania (1899–1903). He served as the first director of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (1901–1935) and a trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation. He was also a friend and adviser to John D. Rockefeller Jr.

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry located in Princeton, New Jersey. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholars, including Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Hermann Weyl, John von Neumann, and Kurt Gödel, many of whom had emigrated from Europe to the United States.

Victor Almon McKusick was an American internist and medical geneticist, and Professor of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore. He was a proponent of the mapping of the human genome due to its use for studying congenital diseases. He is well known for his studies of the Amish. He was the original author and, until his death, remained chief editor of Mendelian Inheritance in Man (MIM) and its online counterpart Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). He is widely known as the "father of medical genetics".

The Flexner Report is a book-length landmark report of medical education in the United States and Canada, written by Abraham Flexner and published in 1910 under the aegis of the Carnegie Foundation. Many aspects of the present-day American medical profession stem from the Flexner Report and its aftermath. The Flexner report has been criticized for introducing policies that encouraged systemic racism.

Abraham Flexner was an American educator, best known for his role in the 20th century reform of medical and higher education in the United States and Canada.

Raymond Pearl was an American biologist, regarded as one of the founders of biogerontology. He spent most of his career at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Pearl was a prolific writer of academic books, papers and articles, as well as a committed populariser and communicator of science. At his death, 841 publications were listed against his name.

Ernst Rüdin was a Swiss-born German psychiatrist, geneticist, eugenicist and Nazi, rising to prominence under Emil Kraepelin and assuming the directorship at the German Institute for Psychiatric Research in Munich. While he has been credited as a pioneer of psychiatric inheritance studies, he also argued for, designed, justified and funded the mass sterilization and clinical killing of adults and children.

The Perelman School of Medicine, commonly known as Penn Med, is the medical school of the University of Pennsylvania, a private research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1765, the Perelman School of Medicine is the oldest medical school in the United States and one of the seven Ivy League medical schools.

Clarence Cook Little was an American genetics, cancer, and tobacco researcher and academic administrator, as well as a proponent of eugenics.

Nathaniel Charles Comfort is an American historian specializing in the history of biology. He is an associate professor in the Institute of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. In 2015, he was appointed the third Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress Chair in Astrobiology at the Library of Congress John W. Kluge Center. He also serves on the advisory council of METI.

William Henry Welch was an American physician, pathologist, bacteriologist, and medical-school administrator. He was one of the "Big Four" founding professors at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. He was the first dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and was also the founder of the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, the first school of public health in the country. Welch was more known for his cogent summations of current scientific work, than his own scientific research. The Johns Hopkins medical school library is also named after Welch. In his lifetime, he was called the "Dean of American Medicine" and received various awards and honors throughout his lifetime and posthumously.

Eliot Trevor Oakeshott Slater MD was a British psychiatrist who was a pioneer in the field of the genetics of mental disorders. He held senior posts at the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases, Queen Square, London, and the Institute of Psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital. He was the author of some 150 scientific papers and the co-author of several books on psychiatric topics, notably on disputed 'physical methods'. From the mid-50s to his death, he co-edited Clinical Psychiatry, the leading textbook for psychiatric trainees.

Guenter B. Risse is an American medical historian. He has written numerous books, including his most recent "Driven by Fear: Epidemics and Isolation in San Francisco's House of Pestilence." The American Association for the History of Medicine awarded him the 1988 William H. Welch Medal for his book Hospital Life in Enlightenment Scotland and its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005. He is Professor Emeritus, Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine, at the University of California, San Francisco, and currently Affiliate Professor of Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The history of medicine in the United States encompasses a variety of approaches to health care in the United States spanning from colonial days to the present. These interpretations of medicine vary from early folk remedies that fell under various different medical systems to the increasingly standardized and professional managed care of modern biomedicine.

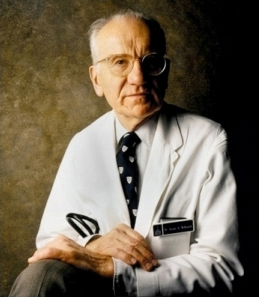

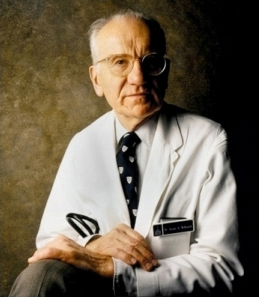

Harry Harris FRS, FCRP, was a British-born biochemist. His work showed that human genetic variation was not rare and disease-causing but instead was common and usually harmless. He was the first to demonstrate, with biochemical tests, that with the exception of identical twins we are all different at the genetic level. This work paved the way for many well-known genetic concepts and procedures such as DNA fingerprinting, the prenatal diagnosis of disorders using genetic markers, the extensive heterogeneity of inherited diseases, and the mapping of human genes to chromosomes

Madge Thurlow Macklin was an American physician known for her work in the field of medical genetics, efforts to make genetics a part of medical curriculum, and participation in the eugenics movement.

Harvey Ernest Jordan was a professor of anatomy and dean of the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Warfield Theobald Longcope was an American pathologist. He served as physician-in-chief of the Johns Hopkins Hospital and president of the American Association of Immunologists, Association of American Physicians, and American Society for Clinical Investigation.

John Duffy (1915–1996) was an American medical historian who wrote books and scholarly journal articles on the history of medical education, public health and epidemics.