Tattvārthasūtra, meaning "On the Nature [artha] of Reality [tattva]" is an ancient Jain text written by Acharya Umaswami in Sanskrit, sometime between the 2nd- and 5th-century CE.

Nemichandra, also known by his epithet Siddhanta Chakravarty, was a Jain acharya from present-day India. He wrote several works including Dravyasamgraha, Gommatsāra, Trilokasara, Labdhisara and Kshapanasara.

Samaya or Samayam is a Sanskrit term referring to the "appointed or proper time, [the] right moment for doing anything." In Indian languages, samayam, or samay in Indo-Aryan languages, is a unit of time.

Mallinatha was the 19th tīrthaṅkara "ford-maker" of the present avasarpiṇī age in Jainism.

The Bhaktāmara Stotra is a Jain religious hymn (stotra) written in Sanskrit. It was authored by Manatunga. The Digambaras believe it has 48 verses while Śvetāmbaras believe it consists of 44 verses.

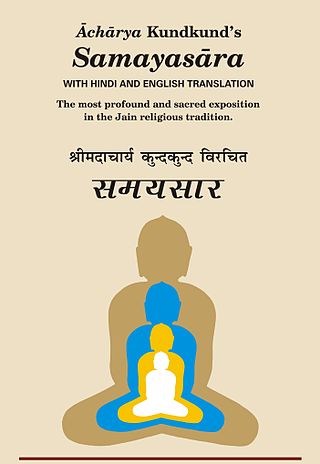

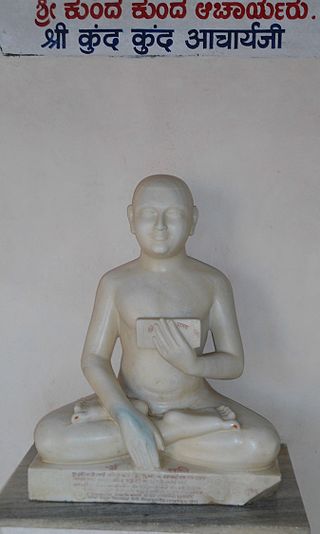

Samayasāra is a famous Jain text composed by Acharya Kundakunda in 439 verses. Its ten chapters discuss the nature of Jīva, its attachment to Karma and Moksha (liberation). Samayasāra expounds the Jain concepts like Karma, Asrava, Bandha (Bondage), Samvara (stoppage), Nirjara (shedding) and Moksha.

Acharya Pujyapada or Pūjyapāda was a renowned grammarian and acharya belonging to the Digambara tradition of Jains. It was believed that he was worshiped by demigods on the account of his vast scholarship and deep piety, and thus, he was named Pujyapada. He was said to be the guru of King Durvinita of the Western Ganga dynasty.

Niyamasāra is a Jain text authored by Acharya Kundakunda, a Digambara Jain acharya. It is described by its commentators as the Bhagavat Shastra. It expounds the path to liberation.

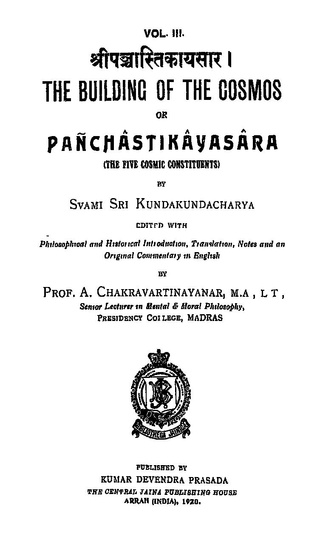

Pañcāstikāyasāra is an ancient Jain text authored by Acharya Kundakunda. Kundakunda explains the Jain concepts of dravya (substance) and Ethics. The work serves as a brief version of the Jaina philosophy. There are total 180 verses written in Prakrit language. The text is about five (panch) āstikāya, substances that have both characteristics, viz. existence as well as body.

Sanskrit moksha or Prakrit mokkha refers to the liberation or salvation of a soul from saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and death. It is a blissful state of existence of a soul, attained after the destruction of all karmic bonds. A liberated soul is said to have attained its true and pristine nature of infinite bliss, infinite knowledge and infinite perception. Such a soul is called siddha and is revered in Jainism.

Jain literature refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit language. Various commentaries were written on these canonical texts by later Jain monks. Later works were also written in other languages, like Sanskrit and Maharashtri Prakrit.

Jīva or Ātman is a philosophical term used within Jainism to identify the soul. As per Jain cosmology, jīva or soul is the principle of sentience and is one of the tattvas or one of the fundamental substances forming part of the universe. The Jain metaphysics, states Jagmanderlal Jaini, divides the universe into two independent, everlasting, co-existing and uncreated categories called the jiva (soul) and the ajiva. This basic premise of Jainism makes it a dualistic philosophy. The jiva, according to Jainism, is an essential part of how the process of karma, rebirth and the process of liberation from rebirth works.

Dravyasaṃgraha is a 10th-century Jain text in Jain Sauraseni Prakrit by Acharya Nemicandra belonging to the Digambara Jain tradition. It is a composition of 58 gathas (verses) giving an exposition of the six dravyas (substances) that characterize the Jain view of the world: sentient (jīva), non-sentient (pudgala), principle of motion (dharma), principle of rest (adharma), space (ākāśa) and time (kāla). It is one of the most important Jain works and has gained widespread popularity. Dravyasaṃgraha has played an important role in Jain education and is often memorized because of its comprehensiveness as well as brevity.

Umaswati, also spelled as Umasvati and known as Umaswami, was an Indian scholar, possibly between 2nd-century and 5th-century CE, known for his foundational writings on Jainism. He authored the Jain text Tattvartha Sutra. Umaswati's work was the first Sanskrit language text on Jain philosophy, and is the earliest extant comprehensive Jain philosophy text accepted as authoritative by all four Jain traditions. His text has the same importance in Jainism as Vedanta Sutras and Yogasutras have in Hinduism.

Digambara is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being Śvetāmbara (white-clad). The Sanskrit word Digambara means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing nor wearing any clothes.

Samantabhadra was a Digambara acharya who lived about the later part of the second century CE. He was a proponent of the Jaina doctrine of Anekantavada. The Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra is the most popular work of Samantabhadra. Samantabhadra lived after Umaswami but before Pujyapada.

Pravacanasāra is a text composed by Jain monk Kundakunda in the second century CE or later. The title means "Essence of the Doctrine" or "Essence of the Scripture", and it largely deals with the correct ascetic and spiritual behavior based on his dualism premise. Kundakunda provides a rationale for nudity among Digambara monks in this text, stating that the duality of self and of others means "neither I belong to others, nor others belong to me, therefore nothing is mine and the ideal way for a monk to live is the way he was born". The text is written in Prakrit language, and it consists of three chapters and 275 verses.

Guņabhadra was a Digambara monk in India. He co-authored Mahapurana along with Jinasena.