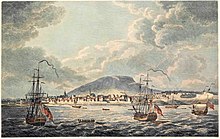

Mackinac Island is an island and resort area, covering 4.35 square miles (11.3 km2) in land area, in the U.S. state of Michigan. The name of the island in Odawa is Michilimackinac and "Mitchimakinak" in Ojibwemowin meaning "Great Turtle". It is located in Lake Huron, at the eastern end of the Straits of Mackinac, between the state's Upper and Lower Peninsulas. The island was long home to an Odawa settlement and previous indigenous cultures before European colonization began in the 17th century. It was a strategic center of the fur trade around the Great Lakes. Based on a former trading post, Fort Mackinac was constructed on the island by the British during the American Revolutionary War. It was the site of two battles during the War of 1812 before the northern border was settled and the US gained this island in its territory.

Emmet County is a county located in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is the northernmost county in the Lower Peninsula. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 34,112, making it the second-most populous county in Northern Michigan. The county seat is Petoskey, which is also the county's largest city.

Readmond Township is a civil township of Emmet County in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 581 at the 2010 census.

Mackinac Island is a city in Mackinac County in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 583.

Mackinaw City is a village at the northernmost point of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. Divided between Cheboygan and Emmet counties, Mackinaw City is the located at the southern end of the Mackinac Bridge, which carries Interstate 75 over the Straits of Mackinac to the Upper Peninsula. Mackinaw City, along with St. Ignace, serves as an access point to Mackinac Island. For these reasons, Mackinaw City is considered one of Michigan's most popular tourist attractions.

The Odawa, believed to derive from an Anishinaabe word meaning "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They have long had territory that crosses the current border between the two countries, and they are federally recognized as Native American tribes in the United States and have numerous recognized First Nations bands in Canada. They are one of the Anishinaabeg, related to but distinct from the Ojibwe and Potawatomi peoples.

Wawatam was an 18th-century Odawa chief who lived in the northern region of present-day Michigan's Lower Peninsula in an area along the Lake Michigan shoreline known by the Odawa as Waganawkezee.

Little Traverse Bay is a small open bay of Lake Michigan. Extending about 10 miles (16 km) into the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, much of the head of the land surrounding Little Traverse Bay, and has become part of the urban areas of Petoskey and Harbor Springs. Little Traverse Bay primarily lies within Emmet County, although a small portion lies within Charlevoix County.

Michilimackinac is derived from an Ottawa Ojibwe name for present-day Mackinac Island and the region around the Straits of Mackinac between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. Early settlers of North America applied the term to the entire region along Lakes Huron, Michigan, and Superior. Today it is considered to be mostly within the boundaries of Michigan, in the United States. Michilimackinac was the original name for present day Mackinac Island and Mackinac County.

Northern Michigan, also known as Northern Lower Michigan, is a region of the U.S. state of Michigan. A popular tourist destination, it is home to several small- to medium-sized cities, extensive state and national forests, lakes and rivers, and a large portion of Great Lakes shoreline. The region has a significant seasonal population much like other regions that depend on tourism as their main industry. Northern Lower Michigan is distinct from the more northerly Upper Peninsula and Isle Royale, which are also located in "northern" Michigan. In the northernmost 21 counties in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, the total population of the region is 506,658 people.

Fort de Buade was a French fort in the present U.S. state of Michigan's Upper Peninsula across the Straits of Mackinac from the northern tip of lower Michigan's "mitten". It was garrisoned between 1683 and 1701. The city of St. Ignace developed at the site, which also had the historic St. Ignace Mission founded by Jesuits. The fort was named after New France's governor at the time, Louis de Buade de Frontenac.

Andrew Jackson Blackbird, also known as Makade-binesi, was an Odawa (Ottawa) tribe leader and historian. He was author of the 1887 book, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan.

Chief Wawatam was a coal-fired steel ship that was based, for most of its 1911–1984 working life, in St. Ignace, Michigan. The vessel was named after a distinguished Ojibwa chief of the 1760s. In initial revenue service, the Chief Wawatam served as a train ferry, passenger ferry and icebreaker that operated year-round at the Straits of Mackinac between St. Ignace and Mackinaw City, Michigan. During the winter months, it sometimes took many hours to cross the five-mile-wide Straits, and Chief Wawatam was fitted with complete passenger hospitality spaces.

Magdelaine La Framboise (1780–1846), born Marguerite-Magdelaine Marcot, was one of the most successful fur traders in the Northwest Territory of the United States, in the area of present-day western Michigan. Of mixed Odawa and French descent, she was fluent in the Odawa, French, English and Ojibwe languages of the region, and partnered with her husband. After he was murdered in 1806, she successfully managed her fur trade business for more than a decade, even against the competition of John Jacob Astor. After retiring from the trade, she built a fine home on Mackinac Island.

For St. Ignatius Church and Cemetery in Port Tobacco Maryland see St. Thomas Manor

Sainte Anne Church, commonly called 'Ste. Anne Church' or 'Ste. Anne's Church', is a Roman Catholic church that serves the parish of Sainte Anne de Michilimackinac in Mackinac Island, Michigan. The Jesuit missionary Claude Dablon inaugurated the rites of the Catholic faith on Mackinac Island in 1670, but the earliest surviving parish records list sacraments performed starting in April 1695. After moving from Fort de Buade to Fort Michilimackinac about 1708 and from Fort Michilimackinac to Mackinac Island in 1781, the parish used a historic log church for decades. It constructed the current church complex starting in 1874 on a site donated by the former fur trader, Magdelaine Laframboise.

The Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians is a state recognized tribe of Ojibwe and Odawa Native Americans, based in the state Michigan. The tribe is headquartered in St. Ignace, Mackinac County and has around 4,000 enrolled members. Today most tribal members live in Mackinac, Chippewa, Emmet, Cheboygan, and Presque Isle counties, however many tribal members are also located throughout the state of Michigan and the United States.

Wabiwindego (d.1837), also spelled Wobwindego, Wobiwidigo, or Wabaningo, and known among the Ojibwe as Waabishkindip, was a leader of the Grand River Band of Ottawa in what would become the U.S. State of Michigan. He negotiated the 1836 Treaty of Washington with the federal government on behalf of the Grand River Ottawa, leading to the admission of the State of Michigan to the Union. Several villages he led formed the basis for several modern Michigan towns, including Lowell, Whitehall, and Montague.

Nissowaquet was an Odawa leader of the Nassauakueton doodem. His father was chief Returning Cloud Kewinaquot and his mother was Nesxesouexite Neskes Mi-Jak-Wa-Ta-Wa. He grew up in Michilimackinac and moved 20 miles (32 km) to L'Arbre Croche with around 180 warriors in 1741.

Monette, also known as Manette, was a Native American enslaved woman of John Askin. She gave birth to three children who were educated and married into prominent families of the Great Lakes regions of present-day Michigan and Ontario, Canada. Her son was John Askin Jr. Daughter Catherine married Captain Samuel Robertson, who operated one of Askin's boats, and was married a second time to Robert Hamilton, founder of Queenston, Ontario. Daughter Madeline was married to Dr. Robert Richardson, the surgeon of the Queen's Rangers stationed at Fort George.