The Cenozoic is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66 million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds, and angiosperms. It is the latest of three geological eras, preceded by the Mesozoic and Paleozoic. The Cenozoic started with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, when many species, including the non-avian dinosaurs, became extinct in an event attributed by most experts to the impact of a large asteroid or other celestial body, the Chicxulub impactor.

The Holocene is the current geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene together form the Quaternary period. The Holocene is an interglacial period within the ongoing glacial cycles of the Quaternary, and is equivalent to Marine Isotope Stage 1.

The Pleistocene is the geological epoch that lasted from c. 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in 2009 by the International Union of Geological Sciences, the cutoff of the Pleistocene and the preceding Pliocene was regarded as being 1.806 million years Before Present (BP). Publications from earlier years may use either definition of the period. The end of the Pleistocene corresponds with the end of the last glacial period and also with the end of the Paleolithic age used in archaeology. The name is a combination of Ancient Greek πλεῖστος (pleîstos), meaning "most", and καινός, meaning "new".

The Quaternary is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ago to the present. As of 2023, the Quaternary Period is divided into two epochs: the Pleistocene and the Holocene ; a third epoch, the Anthropocene, has recently been proposed, but it is not officially recognised by the ICS.

The Younger Dryas, which occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP), was a stadial (cooling) event which marked a return to glacial conditions, temporarily reversing the climatic warming of the preceding Late Glacial Interstadial. The Younger Dryas was the most severe and longest lasting of several interruptions to the warming of the Earth's climate. The end of the Younger Dryas marks the beginning of the current Holocene epoch.

In zoology, megafauna are large animals. The most common thresholds to be a megafauna are weighing over 45 kg (99 lb) or weighing over 1,000 kg (2,200 lb). The first occurrence of the term was in 1876. After the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs, mammals and other vertebrates experienced an expansion in size. Millions of years of evolution led to gigantism on every major land mass. During the Quaternary extinction event, many species of megafauna went extinct as part of a slowly progressing extinction wave that affected ecosystems worldwide.

The Last Glacial Period (LGP), also known colloquially as the Last Ice Age or simply Ice Age, occurred from the end of the Last Interglacial to the end of the Younger Dryas, encompassing the period c. 115,000 – c. 11,700 years ago.

The steppe bison or steppe wisent is an extinct species of bison. It was widely distributed across the mammoth steppe, ranging from Western Europe to eastern Beringia in North America during the Late Pleistocene. It is ancestral to all North American bison, including ultimately modern American bison. Three chronological subspecies, Bison priscus priscus, Bison priscus mediator, and Bison priscus gigas, have been suggested.

There have been five or six major ice ages in the history of Earth over the past 3 billion years. The Late Cenozoic Ice Age began 34 million years ago, its latest phase being the Quaternary glaciation, in progress since 2.58 million years ago.

A glacial period is an interval of time within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate between glacial periods. The Last Glacial Period ended about 15,000 years ago. The Holocene is the current interglacial. A time with no glaciers on Earth is considered a greenhouse climate state.

The term Australian megafauna refers to the megafauna in Australia during the Pleistocene Epoch. Most of these species became extinct during the latter half of the Pleistocene, and the roles of human and climatic factors in their extinction are contested.

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the mammoth steppe, also known as steppe-tundra, was once the Earth's most extensive biome. It stretched east-to-west, from the Iberian Peninsula in the west of Europe, across Eurasia to North America, through Beringia and Canada; from north-to-south, the steppe reached from the arctic islands southward to China. The mammoth steppe was cold and dry, and relatively featureless, though topography and geography varied considerably throughout. Some areas featured rivers which, through erosion, naturally created gorges, gulleys, or small glens. The continual glacial recession and advancement over millennia contributed more to the formation of larger valleys and different geographical features. Overall, however, the steppe is known to be flat and expansive grassland. The vegetation was dominated by palatable, high-productivity grasses, herbs and willow shrubs.

The Chibanian, widely known as the Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. The Chibanian name was officially ratified in January 2020. It is currently estimated to span the time between 0.770 Ma and 0.126 Ma, also expressed as 770–126 ka. It includes the transition in palaeoanthropology from the Lower to the Middle Paleolithic over 300 ka.

The Older Dryas was a stadial (cold) period between the Bølling and Allerød interstadials, about 14,000 years Before Present, towards the end of the Pleistocene. Its date range is not well defined, with estimates varying by 400 years, but its duration is agreed to have been around two centuries.

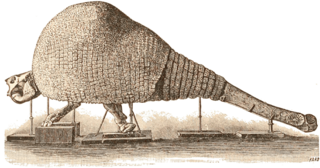

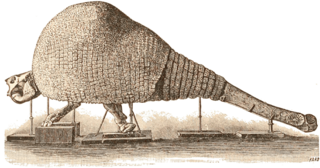

Doedicurus is an extinct genus of glyptodont from North and South America containing one species, D. clavicaudatus. Glyptodonts are a member of the family Chlamyphoridae, which also includes some modern armadillo species, and they are classified in the superorder Xenarthra alongside sloths and anteaters. Being a glyptodont, it was a rotund animal with heavy armor and a carapace. Averaging at an approximate 1,400 kg (3,100 lb), it was one of the largest glyptodonts to have ever lived. Though glyptodonts were quadrupeds, large ones like Doedicurus may have been able to stand on two legs like other xenarthrans. It notably sported a spiked tail club, which may have weighed 40 or 65 kg in life, and it may have swung this in defense against predators or in fights with other Doedicurus at speeds of perhaps 11 m/s.

The Late Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene saw numerous extinctions of predominantly megafaunal animal species, which resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity across the globe. The extinctions during the Late Pleistocene are differentiated from previous extinctions by the widespread absence of ecological succession to replace these extinct megafaunal species, and the regime shift of previously established faunal relationships and habitats as a consequence. The timing and severity of the extinctions varied by region and are thought to have been driven by varying combinations of human and climatic factors. Human impact on megafauna populations is thought to have been driven by hunting ("overkill"), as well as possibly environmental alteration. The relative importance of human vs climatic factors in the extinctions has been the subject of long-running controversy.

The Weichselian glaciation was the last glacial period and its associated glaciation in northern parts of Europe. In the Alpine region it corresponds to the Würm glaciation. It was characterized by a large ice sheet that spread out from the Scandinavian Mountains and extended as far as the east coast of Schleswig-Holstein, northern Poland and Northwest Russia. This glaciation is also known as the Weichselian ice age, Vistulian glaciation, Weichsel or, less commonly, the Weichsel glaciation, Weichselian cold period (Weichsel-Kaltzeit), Weichselian glacial (Weichsel-Glazial), Weichselian Stage or, rarely, the Weichselian complex (Weichsel-Komplex).

The Beringian wolf is an extinct population of wolf that lived during the Ice Age. It inhabited what is now modern-day Alaska, Yukon, and northern British Columbia. Some of these wolves survived well into the Holocene. The Beringian wolf is an ecomorph of the gray wolf and has been comprehensively studied using a range of scientific techniques, yielding new information on their prey species and feeding behaviors. It has been determined that these wolves are morphologically distinct from modern North American wolves and genetically basal to most modern and extinct wolves. The Beringian wolf has not been assigned a subspecies classification and its relationship with the extinct European cave wolf is not clear.

The Pleistocene wolf, also referred to as the Late Pleistocene wolf, is an extinct lineage or ecomorph of the grey wolf. It was a Late Pleistocene 129 Ka – early Holocene 11 Ka hypercarnivore. While comparable in size to a large modern grey wolf, it possessed a shorter, broader palate with large carnassial teeth relative to its overall skull size, allowing it to prey and scavenge on Pleistocene megafauna. Such an adaptation is an example of phenotypic plasticity. It was once distributed across the northern Holarctic. Phylogenetic evidence indicates that despite being much smaller than this prehistoric wolf, the Japanese wolf, which went extinct in the early 20th century, was of a Pleistocene wolf lineage, thus extending its survival to several millennia after its previous estimated extinction around 7,500 years ago.

The wood-pasture hypothesis is a scientific hypothesis positing that open and semi-open pastures and wood-pastures formed the predominant type of landscape in post-glacial temperate Europe, rather than the common belief of primeval forests. The hypothesis proposes that such a landscape would be formed and maintained by large wild herbivores. Although others, including landscape ecologist Oliver Rackham, had previously expressed similar ideas, it was the Dutch researcher Frans Vera, who, in his 2000 book Grazing Ecology and Forest History, first developed a comprehensive framework for such ideas and formulated them into a theorem. Vera's proposals, although highly controversial, came at a time when the role grazers played in woodlands was increasingly being reconsidered, and are credited for ushering in a period of increased reassessment and interdisciplinary research in European conservation theory and practice. Although Vera largely focused his research on the European situation, his findings could also be applied to other temperate ecological regions worldwide, especially the broadleaved ones.