Meetings of the Council

Map of medieval

Rome: Lateran Basilica circled.

On 12 April 769 the Pope opened the synod in the Lateran Basilica. Present were around 52 bishops (or representatives of bishops), [9] including ones from Tuscany and Campania, [10] as well as a large number of priests, deacons, and the laity. [11] The Council met during four sessions, spread over four days, lasting until 15 April. [1] The first sessions of the Council, lasting two days, were dedicated to reviewing the activities of the antipope Constantine II, in which Wilichar of Sens took a leading role. [1] [12]

Constantine was brought before the synod, and was asked how he justified his own accession as a layman to the Apostolic See. Constantine replied that he had been forced to take on the role, as the Roman people had been looking for someone to fix the problems left behind by Pope Paul I. [13] He then confessed to the charges, and threw himself on the mercy of the synod. [11] On the following day however, he retracted his confession, arguing that his actions had not been any different from other papal elections in the past. He pointed to two episcopal elections, those of Sergius, Archbishop of Ravenna, and Stephanus, Bishop of Naples, where the successful candidates had been laymen. [14] Infuriated by his arguments, the Synod ordered Constantine to be beaten and excommunicated from the Church. [11] Constantine's acts and rulings were then publicly burnt before the entire synod, as Pope Stephen III, the bishops, alongside the Roman laity present, all prostrated themselves, singing the Kyrie eleison, and declaring that they had sinned in receiving Holy Communion from the hands of Constantine. [11]

The Third Session (14 April) revolved around revising the rules by which papal elections were held. [1] After a review and discussion on the canons of the Church, as well as recent elections, the Council decreed that no layperson could be made Pope, and that only cardinal deacons or priests, who had been consecrated and had moved through the minor orders, could be elected pope. [15] The Council then mandated that from the time of the Council onward, the laity could not participate in the election of a pope. Prohibitions were placed upon the presence of armed men, or of soldiers from Tuscany and the Campania, during the papal election. [16] Once, however, the election had been held by the clergy, and a pope selected, the Roman army and people were to greet and acknowledge the pope-elect before he was escorted to the Lateran Palace. [16]

The third session on that same day saw the issuing of decrees with regards to the ordinations undertaken by the antipope Constantine. [17] The synod decided that the bishops, priests, and deacons whom Constantine had ordained were to once again return to their previous station that they held prior to Constantine's appointment. [16] However, the synod also stated that if those who had been consecrated bishops by Constantine were re-elected via a canonical method, they might be reconciled and restored to the episcopate by the Pope. [16] The Pope could also reinstate priests and deacons; however, any layperson who had been ordained a priest or deacon by Constantine was consigned to spend the rest of his life in a monastery, and none could ever be promoted to a higher religious office. [16]

The final session of the Council, held on 15 April, was dedicated to providing a ruling concerning the ongoing Iconoclast controversy. Reviewing the writings of the Church Fathers, the Council decreed that it was permissible and desirable for Christians to venerate icons. [18] It confirmed the rulings of the Council of Rome in 731 concerning the valid use of images. [19] The synod then condemned the Council of Hieria and anathematized its iconoclastic rulings. [18] Finally, it collected additional texts in support of the veneration of icons, including portions of a letter from the three eastern patriarchs to Pope Paul I. [19]

Once the meetings had been concluded, a procession of clergy and people walked barefoot to St. Peter's Basilica. There, the Council's decrees were announced, anathemas were invoked, condemning any who violated the decrees, and both were written up for exposition to the people. [18]

The bishops who had been consecrated by Constantine seem to have been on the whole reconciled by the Pope. [18] Pope Stephen III, however, never returned priests or deacons to the rank to which the antipope Constantine had raised them. [18] In general, the sacraments administered by Constantine, apart from Baptism and Confirmation, were repeated under Stephen. [18] The iconoclast portion of the Council was meant to clearly align Rome with Francia, and to signal to the Franks that the Byzantines were heretics. [1] Significantly, the Roman dating of the Council was no longer by the years of the Byzantine Emperors, and thus apparently indicating that the Council was not recognising imperial sovereignty whilst the Church was in schism. [20]

The rulings of this Council concerning the election of the popes were gradually eroded over the course of the decades and centuries. As early as 827, the election of Pope Valentine saw the election of a pope where the nobility and people actively took part in the election. This continued development, and the ignoring of the Council's rulings, saw the Papacy reach its nadir during the 10th century, when the papacy became the plaything of the Roman aristocracy. [18]

The First Council of the Lateran was the 9th ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church. It was convoked by Pope Callixtus II in December 1122, immediately after the Concordat of Worms. The council sought to bring an end to the practice of the conferring of ecclesiastical benefices by people who were laymen, free the election of bishops and abbots from secular influence, clarify the separation of spiritual and temporal affairs, re-establish the principle that spiritual authority resides solely in the Church and abolish the claim of the Holy Roman Emperor to influence papal elections.

Pope Alexander II, born Anselm of Baggio, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1061 to his death in 1073. Born in Milan, Anselm was deeply involved in the Pataria reform movement. Elected according to the terms of his predecessor's bull, In nomine Domini, Anselm's was the first election by the cardinals without the participation of the people and minor clergy of Rome. He also authorized the Norman Conquest of England in 1066.

Pope Miltiades, also known as Melchiades the African, was the bishop of Rome from 311 to his death on 10 or 11 January 314. It was during his pontificate that Emperor Constantine the Great issued the Edict of Milan (313), giving Christianity legal status within the Roman Empire. The pope also received the palace of Empress Fausta where the Lateran Palace, the papal seat and residence of the papal administration, would be built. At the Lateran Council, during the schism with the Church of Carthage, Miltiades condemned the rebaptism of apostatised bishops and priests, a teaching of Donatus Magnus.

Pope Boniface IV was the bishop of Rome from 608 to his death. Boniface had served as a deacon under Pope Gregory I, and like his mentor, he ran the Lateran Palace as a monastery. As pope, he encouraged monasticism. With imperial permission, he converted the Pantheon into a church. In 610, he conferred with Bishop Mellitus of London regarding the needs of the English Church. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church with a universal feast day on 8 May.

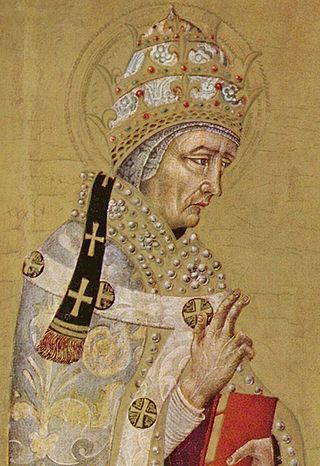

Pope Stephen III was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 7 August 768 to his death. Stephen was a Benedictine monk who worked in the Lateran Palace during the reign of Pope Zachary. In the midst of a tumultuous contest by rival factions to name a successor to Pope Paul I, Stephen was elected with the support of the Roman officials. He summoned the Lateran Council of 769, which sought to limit the influence of the nobles in papal elections. The Council also opposed iconoclasm.

Pope Zachary was the bishop of Rome from 28 November 741 to his death. He was the last pope of the Byzantine Papacy. Zachary built the original church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, forbade the traffic of slaves in Rome, negotiated peace with the Lombards, and sanctioned Pepin the Short's usurpation of the Frankish throne from Childeric III. Zachary is regarded as a capable administrator and a skillful and subtle diplomat in a dangerous time.

Pope Valentine was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States for two months in 827. He was unusually close to his predecessor, Eugene II, rumoured to be his son or his lover, and became pope before being ordained as a priest. He was a nobleman and elected by nobility, which later became the custom.

Pope Zosimus was the bishop of Rome from 18 March 417 to his death on 26 December 418. He was born in Mesoraca, Calabria. Zosimus took a decided part in the protracted dispute in Gaul as to the jurisdiction of the See of Arles over that of Vienne, giving energetic decisions in favour of the former, but without settling the controversy. His fractious temper coloured all the controversies in which he took part, in Gaul, Africa and Italy, including Rome, where at his death the clergy were very much divided.

Pope Leo VIII was a Roman prelate who claimed the Holy See from 963 until 964 in opposition to John XII and Benedict V and again from 23 June 964 to his death. Today he is considered by the Catholic Church to have been an antipope during the first period and the legitimate Pope of Rome during the second. An appointee of Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, Leo VIII's pontificate occurred after the period known as the saeculum obscurum.

Pope Symmachus was the bishop of Rome from 22 November 498 to his death. His tenure was marked by a serious schism over who was elected pope by a majority of the Roman clergy.

Benedict X, born Giovanni, was elected to succeed Pope Stephen IX on 5 April 1058, but was opposed by a rival faction that elected Nicholas II. He fled Rome on 24 January 1059 and is today generally regarded as an antipope.

Antipope Constantine II was a Roman prelate who claimed the papacy from 28 June 767 to 6 August 768. He was overthrown through the intervention of the Lombards and tortured before he was condemned and expelled from the Church during the Lateran Council of 769.

Antipope Eulalius was antipope from December 418 to April 419. Elected in a dual election with Pope Boniface I, he eventually lost out to Boniface and became bishop of Napete.

Antipope Philip was an antipope who held office for just one day, on 31 July 768.

The Diocese of Albano is a suburbicarian see of the Roman Catholic Church in a diocese in Italy, comprising seven towns in the Province of Rome. Albano Laziale is situated some 15 kilometers from Rome, on the Appian Way.

The Diocese of Porto–Santa Rufina is a suburbicarian diocese of the Diocese of Rome and a diocese of the Catholic Church in Italy. It was formed from the union of two dioceses. The diocese of Santa Rufina was also formerly known as Silva Candida.

Cuno of Praeneste was a German Cardinal and papal legate, an influential diplomatic figure of the early 12th century, active in France and Germany. He held numerous synods throughout Europe, and excommunicated the Emperor Henry V numerous times, in the struggle over the issue of lay investiture of ecclesiastical offices. He spent six years promoting the acceptance of Thurstan of York as archbishop by King Henry I of England, without making York subject to Canterbury. He was seriously considered for election to the papacy in 1119, which he refused.

The selection of the pope, the bishop of Rome and supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church, prior to the promulgation of In nomine Domini in 1059 varied throughout history. Popes were often appointed by their predecessors or by political rulers. While some kind of election often characterized the procedure, an election that included meaningful participation of the laity was rare, especially as the popes' claims to temporal power solidified into the Papal States. The practice of papal appointment during this period would later result in the jus exclusivae, i.e., a right to veto the selection that Catholic monarchs exercised into the twentieth century.

The Synods of Rome in 731 were two synods held in St. Peter’s Basilica in the year 731 under the authority of Pope Gregory III to defend the practice of Icon veneration.

The Constitutum Silvestri is one of five fictitious stories known collectively as the Symmachian forgeries, that arose between 501 and 502 at the time of the political battle for the papacy between Pope Symmachus (498-514) and antipope Laurentius.