Etruscan was the language of the Etruscan civilization in the ancient region of Etruria, in Etruria Padana and Etruria Campana in what is now Italy. Etruscan influenced Latin but was eventually completely superseded by it. The Etruscans left around 13,000 inscriptions that have been found so far, only a small minority of which are of significant length; some bilingual inscriptions with texts also in Latin, Greek, or Phoenician; and a few dozen purported loanwords. Attested from 700 BC to AD 50, the relation of Etruscan to other languages has been a source of long-running speculation and study, with it mostly being referred to as one of the Tyrsenian languages, at times as an isolate and a number of other less well-known theories.

Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and religion. As the Etruscan civilization was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC, the Etruscan religion and mythology were partially incorporated into ancient Roman culture, following the Roman tendency to absorb some of the local gods and customs of conquered lands. The first attestations of an Etruscan religion can be traced back to the Villanovan culture.

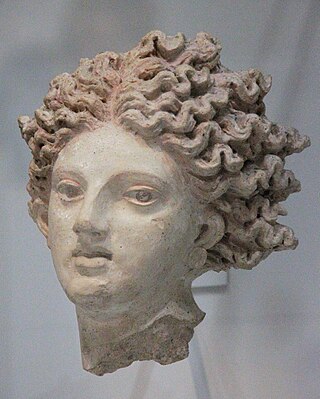

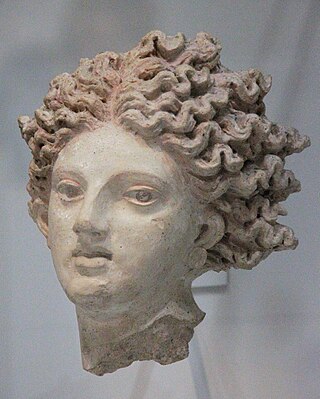

Menrva was an Etruscan goddess of war, art, wisdom, and medicine. She contributed much of her character to the Roman Minerva. She was the child of Uni and Tinia.

The Pyrgi Tablets are three golden plates inscribed with a bilingual Phoenician–Etruscan dedicatory text. They are the oldest historical source documents from pre-Roman Italy and are rare examples of texts in these languages. They were discovered in 1964 during a series of excavations at the site of ancient Pyrgi, on the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy in Latium (Lazio). The text records the foundation of a temple and its dedication to the Phoenician goddess Astarte, who is identified with the Etruscan supreme goddess Uni in the Etruscan text. The temple's construction is attributed to Thefarie Velianas, ruler of the nearby city of Caere.

The Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis is the longest Etruscan text and the only extant linen book, dated to the 3rd century BC, making it arguably the oldest extant European book. Much of it is untranslated because of the lack of knowledge about the Etruscan language, though the words and phrases which can be understood indicate that the text is most likely a ritual calendar. Miles Beckwith points out with regard to this text that "in the last thirty or forty years, our understanding of Etruscan has increased substantially," and L. B. van der Meer has published a word-by-word analysis of the entire text.

Maris was an Etruscan god often depicted as an infant or child and given many epithets, including Mariś Halna, Mariś Husrnana, and Mariś Isminthians. He was the son of Hercle, the Etruscan equivalent of Heracles. On two bronze mirrors, Maris appears in scenes depicting an immersion rite presumably to ensure his immortality. Massimo Pallottino noted that Maris might have been connected to stories about the centaur Mares, the legendary ancestor of the Ausones, who underwent a triple death and resurrection.

The Tabula Capuana, is an ancient terracotta slab, 50 by 60 cm, with a long inscribed text in Etruscan, dated to around 470 BCE, apparently a ritual calendar. About 390 words are legible, making it the second-most extensive surviving Etruscan text. The longest is the linen book (Liber Linteus), also a ritual calendar, used in ancient Egypt for mummy wrappings, now at Zagreb. The Tabula Capuana is located in the Altes Museum, Berlin.

Calu is an epithet of the Etruscan chthonic fire god Śuri as god of the underworld, roughly equivalent to the Greek god Hades ; moroeover, as with Hades, this god-name was also used as a synonym for the underworld itself.

The Tabula Cortonensis is a 2200-year-old, inscribed bronze tablet in the Etruscan language, discovered in Cortona, Italy. It may record for posterity the details of an ancient legal transaction which took place in the ancient Tuscan city of Cortona, known to the Etruscans as Curtun. Its 40-line, 200-word, two-sided inscription is the third longest inscription found in the Etruscan language, after the Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis and the Tabula Capuana, and the longest discovered in the 20th century.

The Cippus Perusinus is a stone tablet (cippus) discovered on the hill of San Marco, in Perugia, Italy, in 1822. The tablet bears 46 lines of incised Etruscan text, about 130 words. The cippus, which seems to have been a border stone, appears to display a text dedicating a legal contract between the Etruscan families of Velthina and Afuna, regarding the sharing or use, including water rights, of a property upon which there was a tomb belonging to the noble Velthinas.

Lammert Bouke van der Meer is a Dutch classicist and classical archaeologist specialized in Etruscology. He studied classics and archaeology at the University of Groningen, and received his Ph.D. from the same university in 1978 with a dissertation entitled Etruscan urns from Volterra. Studies on mythological representations, I-II. Van der Meer is retired associate professor of Classical Archaeology at Leiden University.

The Liver of Piacenza is an Etruscan artifact found in a field on September 26, 1877, near Gossolengo, in the province of Piacenza, Italy, now kept in the Municipal Museum of Piacenza, in the Palazzo Farnese.

Catha is a female Etruscan lunar or solar deity, who may also be connected to childbirth, and has a connection to the underworld. Catha is also the goddess of the south sanctuary at Pyrgi, Italy.

Culsans (Culśanś) is an Etruscan deity, known from four inscriptions and a variety of iconographical material which includes coins, statuettes, and a sarcophagus. Culśanś is usually rendered as a male deity with two faces and at least two statuettes depicting him have been found in close association with city gates. These characteristics suggest that he was a protector of gateways, who could watch over the gate with two pairs of eyes.

Lur is an Etruscan underworld deity with not much known history. Lur does not have many depictions but the ones that have been found show the deity as a male. He has been noted to be associated with a prophetic nature, while also bearing oracular and martial characteristics. He has been linked to another deity by the name of Laran, which, it has been suggested, is where Lur derives his name from. The context of the name has been associated with darkness and the underworld. A fifth century vase found near a sanctuary in San Giovenale bears an inscription that translates: "I am Lurs, that of Laran." Another inscription has been found with the spelling lartla, noting relations to a Lar, which gives a label to Lur that describes features of protection. The name may be related to Latin luridus "pale".

Maria Bonghi Jovino is an Italian archaeologist. Bonghi Jovino was Professor of Etruscology and Italic Archaeology at the University of Milan.

Apulu, also syncopated as Aplu, is an epithet of the Etruscan fire god Śuri as chthonic sky god, roughly equivalent to the Greco-Roman god Apollo. Their names are associated on Pyrgi inscriptions too. The name Apulu or Aplu did not come directly from Greece but via a Latin center, probably Palestrina.

Śuri, later latinized as Soranus, was an ancient Etruscan deity, also venerated by other populations of central Italy and later adopted into ancient Roman religion.

Manth, latinized as Mantus, is an epithet of the Etruscan chthonic fire god Śuri as god of the underworld; this name was primarily used in the Po Valley, as described by Servius, but a dedication to the god manθ from the Archaic period was found in a sanctuary in Pontecagnano, Southern Italy. His name is thought to be the origin of Mantua, the birthplace of Virgil.