Related Research Articles

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River – specifically, to a designated Indian Territory. The Indian Removal Act, the key law which authorized the removal of Native tribes, was signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830. Although Jackson took a hard line on Indian removal, the law was enforced primarily during the Martin Van Buren administration. After the enactment of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, approximately 60,000 members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands, with thousands dying during the Trail of Tears.

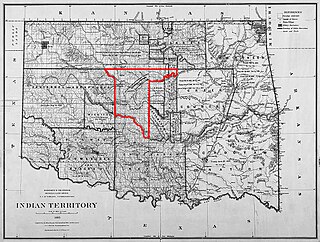

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as a sovereign independent state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the Southeastern United States to newly designated Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. The Cherokee removal in 1838 was brought on by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1828, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush.

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminoles. Americans of European descent classified them as "civilized" because they had adopted attributes of the Anglo-American culture.

The American Dawes Commission, named for its first chairman Henry L. Dawes, was authorized under a rider to an Indian Office appropriation bill, March 3, 1893. Its purpose was to convince the Five Civilized Tribes to agree to cede tribal title of Indian lands, and adopt the policy of dividing tribal lands into individual allotments that was enacted for other tribes as the Dawes Act of 1887. In November 1893, President Grover Cleveland appointed Dawes as chairman, and Meridith H. Kidd and Archibald S. McKennon as members.

The Unassigned Lands in Oklahoma were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek (Muskogee) and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled. By 1883, it was bounded by the Cherokee Outlet on the north, several relocated Indian reservations on the east, the Chickasaw lands on the south, and the Cheyenne-Arapaho reserve on the west. The area amounted to 1,887,796.47 acres.

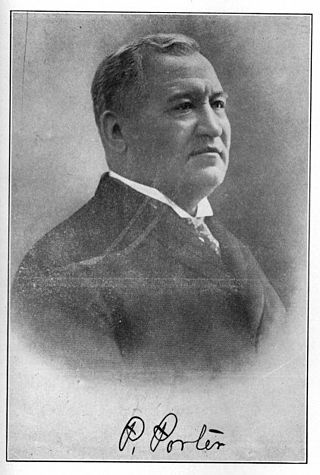

Pleasant Porter, was an American Indian statesman and the last elected Principal Chief of the Creek Nation, serving from 1899 until his death.

The State of Sequoyah was a proposed state to be established from the Indian Territory in the eastern part of present-day Oklahoma. In 1905, with the end of tribal governments looming, Native Americans of the Five Civilized Tribes—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole—in Indian Territory proposed to create a state as a means to retain control of their lands. Their intention was to have a state under Native American constitution and governance. The proposed state was to be named in honor of Sequoyah, the Cherokee who created a writing system in 1825 for the Cherokee language.

The Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee, Oklahoma, showcases the art, history, and culture of the so-called "Five Civilized Tribes": the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole tribes. Housed in the historic Union Indian Agency building, the museum opened in 1966.

The United States Indian Police (USIP) was organized in 1880 by John Q. Tufts, the Indian Commissioner in Muskogee, Indian Territory, to police the Five Civilized Tribes. Their mission is to "provide justice services and technical assistance to federally recognized Indian tribes." The USIP, after its founding in 1880, recruited many of their police officers from the ranks of the existing Indian Lighthorsemen. Unlike the Lighthorse who were under the direction of the individual tribes, the USIP was under the direction of the Indian agent assigned to the Union Agency. Many of the US Indian police officers were given Deputy U.S. Marshal commissions that allowed them to cross jurisdictional boundaries and also to arrest non-Indians.

Indian tribal police are police officers hired by Native American tribes. The largest tribal police agency is the Navajo Nation Police Department and the second largest is the Cherokee Nation Marshal Service.

During the American Civil War, most of what is now the U.S. state of Oklahoma was designated as the Indian Territory. It served as an unorganized region that had been set aside specifically for Native American tribes and was occupied mostly by tribes which had been removed from their ancestral lands in the Southeastern United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830. As part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Indian Territory was the scene of numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles involving both Native American units allied with the Confederate States of America and Native Americans loyal to the United States government, as well as other Union and Confederate troops.

The Yowani were a historical group of Choctaw people who lived in Texas. Yowani was also the name of a preremoval Choctaw village.

The Cherokee Male Seminary was a tribal college established in 1846 by the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory. Opening in 1851, it was one of the first institutions of higher learning in the United States to be founded west of the Mississippi River.

The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention was an American Indian-led attempt to secure statehood for Indian Territory as an Indian-controlled jurisdiction, separate from the Oklahoma Territory. The proposed state was to be called the State of Sequoyah.

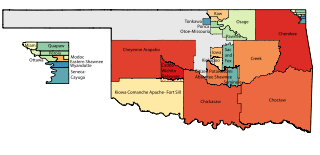

Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area is a statistical entity identified and delineated by federally recognized American Indian tribes in Oklahoma as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's 2010 Census and ongoing American Community Survey. Many of these areas are also designated Tribal Jurisdictional Areas, areas within which tribes will provide government services and assert other forms of government authority. They differ from standard reservations, such as the Osage Nation of Oklahoma, in that allotment was broken up and as a consequence their residents are a mix of native and non-native people, with only tribal members subject to the tribal government. At least five of these areas, those of the so-called five civilized tribes of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole, which cover 43% of the area of the state, are recognized as reservations by federal treaty, and thus not subject to state law or jurisdiction for tribal members.

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history an explanation of the Oklahoma Organic Act needs a historic perspective. In general, the Oklahoma Organic Act may be viewed as one of a series of legislative acts, from the time of Reconstruction, enacted by Congress in preparation for the creation of a united State of Oklahoma. The Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory, and Indian Territory that were Organized incorporated territories of the United States out of the old "unorganized" Indian Territory. The Oklahoma Organic Act was one of several acts whose intent was the assimilation of the tribes in Oklahoma and Indian Territories through the elimination of tribes' communal ownership of property.

On the eve of the American Civil War in 1861, a significant number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas had been relocated from the Southeastern United States to Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi. The inhabitants of the eastern part of the Indian Territory, the Five Civilized Tribes, were suzerain nations with established tribal governments, well established cultures, and legal systems that allowed for slavery. Before European Contact these tribes were generally matriarchial societies, with agriculture being the primary economic pursuit. The bulk of the tribes lived in towns with planned streets, residential and public areas. The people were ruled by complex hereditary chiefdoms of varying size and complexity with high levels of military organization.

Isparhecher, sometimes spelled "Isparhecker," and also known as Is-pa-he-che and Spa-he-cha, was known as a political leader of the opposition in the Creek Nation in the post-Civil War era. He led a group that supported traditional ways and was opposed to the assimilation encouraged by Chief Samuel Checote and others.

Samuel Checote (1819–1884) (Muscogee) was a political leader, military veteran, and a Methodist preacher in the Creek Nation, Indian Territory. He served two terms as the first principal chief of the tribe to be elected under their new constitution created after the American Civil War. He had to deal with continuing tensions among his people, as traditionalists opposed assimilation to European-American ways.

References

- ↑ Luna-Firebaugh, Eileen (15 February 2007). Luna-Firebaugh, Eileen. Tribal Policing: Asserting Sovereignty, Seeking Justice. 2007. University of Arizona Press. Available on Google Books. Retrieved March 30, 2010. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816524341. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Burton, Art. T. "Oklahoma's Frontier Indian Police." Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine (1996). Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. "Choctaw Lighthorsemen." Archived 2014-04-14 at the Wayback Machine 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- 1 2 Foreman, Carolyn Thomas. "The Light-Horse in the Indian Territory." Archived 2012-11-02 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ↑ ""Constitution of the Choctaw Nation. October 1838." Article 3 Section 8". Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ↑ Mihesuah, Devon Abbott (2009). Choctaw Crime and Punishment, 1884–1907 Archived 2022-04-07 at the Wayback Machine . University of Oklahoma. ISBN 978-0-8061-4052-0. Available on Google Books. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Treaty with the Creek Nation, July 10, 1861." Archived May 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ↑ Meserve, John Bartlett. Chronicles of Oklahoma "Chief Pleasant Porter." Archived 2015-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Seminole Light Horse Police". Seminolenation-indianterritory.org. January 18, 2013. Archived from the original on December 9, 2004. Retrieved October 29, 2004.