Related Research Articles

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Biological weapons are living organisms or replicating entities. Entomological (insect) warfare is a subtype of biological warfare.

Bioterrorism is terrorism involving the intentional release or dissemination of biological agents. These agents include bacteria, viruses, insects, fungi, and/or their toxins, and may be in a naturally occurring or a human-modified form, in much the same way as in biological warfare. Further, modern agribusiness is vulnerable to anti-agricultural attacks by terrorists, and such attacks can seriously damage economy as well as consumer confidence. The latter destructive activity is called agrobioterrorism and is a subtype of agro-terrorism.

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea lasting a few days. Vomiting and muscle cramps may also occur. Diarrhea can be so severe that it leads within hours to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. This may result in sunken eyes, cold skin, decreased skin elasticity, and wrinkling of the hands and feet. Dehydration can cause the skin to turn bluish. Symptoms start two hours to five days after exposure.

A pandemic is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic diseases with a stable number of infected individuals such as recurrences of seasonal influenza are generally excluded as they occur simultaneously in large regions of the globe rather than being spread worldwide.

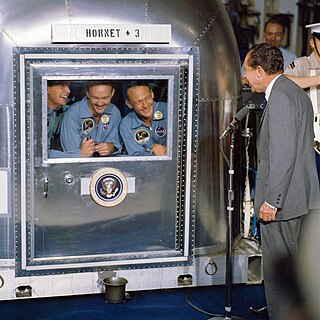

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been exposed to a communicable disease, yet do not have a confirmed medical diagnosis. It is distinct from medical isolation, in which those confirmed to be infected with a communicable disease are isolated from the healthy population. Quarantine considerations are often one aspect of border control.

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Infection typically occurs by contact with the skin, inhalation, or intestinal absorption. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The skin form presents with a small blister with surrounding swelling that often turns into a painless ulcer with a black center. The inhalation form presents with fever, chest pain and shortness of breath. The intestinal form presents with diarrhea, abdominal pains, nausea and vomiting.

Biodefense refers to measures to counter biological threats, reduce biological risks, and prepare for, respond to, and recover from bioincidents, whether naturally occurring, accidental, or deliberate in origin and whether impacting human, animal, plant, or environmental health. Biodefense measures often aim to improve biosecurity or biosafety. Biodefense is frequently discussed in the context of biological warfare or bioterrorism, and is generally considered a military or emergency response term.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1, the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus. The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the syndrome caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak. In the 2010s, Chinese scientists traced the virus through the intermediary of Asian palm civets to cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township, Yunnan.

Joshua Lederberg, ForMemRS was an American molecular biologist known for his work in microbial genetics, artificial intelligence, and the United States space program. He was 33 years old when he won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and exchange genes. He shared the prize with Edward Tatum and George Beadle, who won for their work with genetics.

A cordon sanitaire is the restriction of movement of people into or out of a defined geographic area, such as a community, region, or country. The term originally denoted a barrier used to stop the spread of infectious diseases. The term is also often used metaphorically, in English, to refer to attempts to prevent the spread of an ideology deemed unwanted or dangerous, such as the containment policy adopted by George F. Kennan against the Soviet Union.

On 2 April 1979, spores of Bacillus anthracis were accidentally released from a Soviet military research facility in the city of Sverdlovsk, Soviet Union. The ensuing outbreak of the disease resulted in the deaths of at least 68 people, although the exact number of victims remains unknown. The cause of the outbreak was denied for years by the Soviet authorities, which blamed the deaths on consumption of tainted meat from the area, and subcutaneous exposure due to butchers handling the tainted meat. The accident was the first major indication in the Western world that the Soviet Union had embarked upon an offensive programme aimed at the development and large-scale production of biological weapons.

Jeanne Harley Guillemin was an American medical anthropologist and author, who for 25 years taught at Boston College as a professor of Sociology and for over ten years was a senior fellow in the Security Studies Program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She was an authority on biological weapons and published four books on the topic.

Sentinel species are organisms, often animals, used to detect risks to humans by providing advance warning of a danger. The terms primarily apply in the context of environmental hazards rather than those from other sources. Some animals can act as sentinels because they may be more susceptible or have greater exposure to a particular hazard than humans in the same environment. People have long observed animals for signs of impending hazards or evidence of environmental threats. Plants and other living organisms have also been used for these purposes.

Walter Ian Lipkin is the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a professor of Neurology and Pathology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. He is also director of the Center for Infection and Immunity, an academic laboratory for microbe hunting in acute and chronic diseases. Lipkin is internationally recognized for his work with West Nile virus, SARS and COVID-19.

Howard Markel is an American physician and medical historian. At the end of 2023, Markel retired from the University of Michigan Medical School, where he served as the George E. Wantz Distinguished Professor of the History of Medicine and Director of the University's Center for the History of Medicine. He was also a professor of psychiatry, health management and policy, history, and pediatrics and communicable diseases. Markel writes extensively on major topics and figures in the history of medicine and public health.

Daniel R. Lucey is an American physician, researcher, clinical professor of medicine of infectious diseases at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, and a research associate in anthropology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, where he has co-organised an exhibition on eight viral outbreaks.

The public health measures associated with the COVID-19 pandemic effectively contained and reduced the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus on a global scale between the years 2020–2023, and had several other positive effects on the natural environment of planet Earth and human societies as well, including improved air quality and oxygen levels due to reduced air and water pollution, lower crime rates across the world, and less frequent violent crimes perpetrated by violent non-state actors, such as ISIS and other Islamic terrorist organizations.

References

- ↑ "Emergencies, preparedness, response: Anthrax". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 23 February 2003. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 ""Пора нашим властям и военным назад оборачиваться"". Новая газета - Novayagazeta.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ Meselson, Matthew; Guillemin, J; Hugh-Jones, Martin; Langmuir, A; Popova, I; Shelokov, A; Yampolskaya, O (1 December 1994). "The Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak of 1979". Science. 266 (5188): 1202–8. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1202M. doi:10.1126/science.7973702. PMID 7973702.

- 1 2 "PUBLIC HEALTH RESPONSE". www.ph.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Sverdlovsk Anthrax Outbreak of 1979". www.ph.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ "1998 - Anthrax, Russian Federation". www.who.int. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ↑ Jernigan DB; Raghunathan PL; Bell BP; Brechnert R; Bresnitz EA; Butler JC; Cetron M; et al. (October 2002). "Investigation of Bioterrorism-Related Anthrax, United States, 2001: Epidemiological Findings". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (10): 1019–1028. doi:10.3201/eid0810.020353. PMC 2730292 . PMID 12396909.

- ↑ Lipton, Eric (8 August 2008). "Doubts Persist Among Anthrax Suspect's Colleagues". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ↑ Daw, Daniel (30 October 2014). "Anthrax outbreak causes quarantine of Indian village". BioPrepWatch. Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Anthrax scare in Jharkhand's Simdega". The Times of India. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ Herriman, Robert (31 October 2014). "India: Anthrax outbreak prompts quarantine of Simdega district village". Outbreak News Today. Tampa, Florida: The Global Dispatch, Inc. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Anthrax outbreak triggered by climate change kills boy in Arctic Circle". The Guardian. August 2016.

- ↑ "1,500 reindeer dead, 40 humans hospitalized amid anthrax outbreak in Siberia". VICE News. 30 July 2016.

- ↑ "Worst Anthrax Outbreak in Decades Strikes Farms in France". Live Science . 20 August 2018.