The uncertainty principle, also known as Heisenberg's indeterminacy principle, is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics. It states that there is a limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties, such as position and momentum, can be simultaneously known. In other words, the more accurately one property is measured, the less accurately the other property can be known.

Quantum superposition is a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics that states that linear combinations of solutions to the Schrödinger equation are also solutions of the Schrödinger equation. This follows from the fact that the Schrödinger equation is a linear differential equation in time and position. More precisely, the state of a system is given by a linear combination of all the eigenfunctions of the Schrödinger equation governing that system.

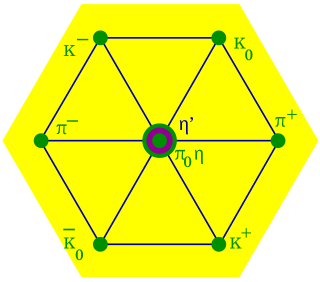

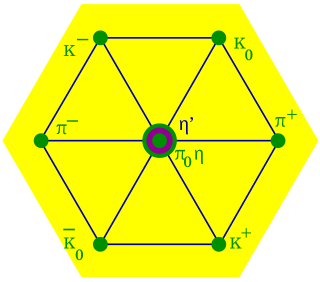

In nuclear physics and particle physics, isospin (I) is a quantum number related to the up- and down quark content of the particle. Isospin is also known as isobaric spin or isotopic spin. Isospin symmetry is a subset of the flavour symmetry seen more broadly in the interactions of baryons and mesons.

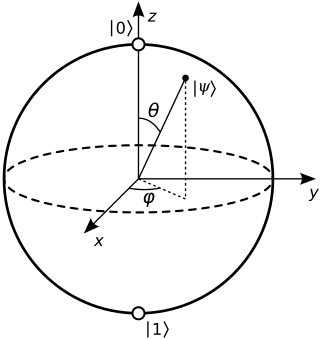

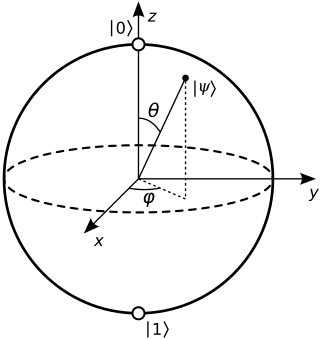

In quantum mechanics and computing, the Bloch sphere is a geometrical representation of the pure state space of a two-level quantum mechanical system (qubit), named after the physicist Felix Bloch.

In particle physics, the quark model is a classification scheme for hadrons in terms of their valence quarks—the quarks and antiquarks that give rise to the quantum numbers of the hadrons. The quark model underlies "flavor SU(3)", or the Eightfold Way, the successful classification scheme organizing the large number of lighter hadrons that were being discovered starting in the 1950s and continuing through the 1960s. It received experimental verification beginning in the late 1960s and is a valid and effective classification of them to date. The model was independently proposed by physicists Murray Gell-Mann, who dubbed them "quarks" in a concise paper, and George Zweig, who suggested "aces" in a longer manuscript. André Petermann also touched upon the central ideas from 1963 to 1965, without as much quantitative substantiation. Today, the model has essentially been absorbed as a component of the established quantum field theory of strong and electroweak particle interactions, dubbed the Standard Model.

LOCC, or local operations and classical communication, is a method in quantum information theory where a local (product) operation is performed on part of the system, and where the result of that operation is "communicated" classically to another part where usually another local operation is performed conditioned on the information received.

Relational quantum mechanics (RQM) is an interpretation of quantum mechanics which treats the state of a quantum system as being relational, that is, the state is the relation between the observer and the system. This interpretation was first delineated by Carlo Rovelli in a 1994 preprint, and has since been expanded upon by a number of theorists. It is inspired by the key idea behind special relativity, that the details of an observation depend on the reference frame of the observer, and uses some ideas from Wheeler on quantum information.

Quantum walks are quantum analogues of classical random walks. In contrast to the classical random walk, where the walker occupies definite states and the randomness arises due to stochastic transitions between states, in quantum walks randomness arises through: (1) quantum superposition of states, (2) non-random, reversible unitary evolution and (3) collapse of the wave function due to state measurements.

In applied mathematics, the numerical sign problem is the problem of numerically evaluating the integral of a highly oscillatory function of a large number of variables. Numerical methods fail because of the near-cancellation of the positive and negative contributions to the integral. Each has to be integrated to very high precision in order for their difference to be obtained with useful accuracy.

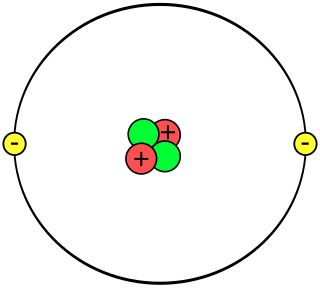

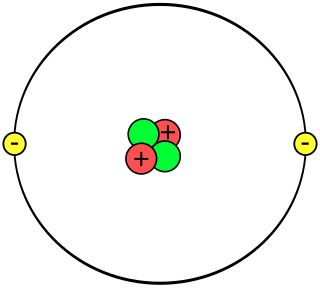

A helium atom is an atom of the chemical element helium. Helium is composed of two electrons bound by the electromagnetic force to a nucleus containing two protons along with two neutrons, depending on the isotope, held together by the strong force. Unlike for hydrogen, a closed-form solution to the Schrödinger equation for the helium atom has not been found. However, various approximations, such as the Hartree–Fock method, can be used to estimate the ground state energy and wavefunction of the atom. Historically, the first such helium spectrum calculation was done by Albrecht Unsöld in 1927. Its success was considered to be one of the earliest signs of validity of Schrödinger's wave mechanics.

The toric code is a topological quantum error correcting code, and an example of a stabilizer code, defined on a two-dimensional spin lattice. It is the simplest and most well studied of the quantum double models. It is also the simplest example of topological order—Z2 topological order (first studied in the context of Z2 spin liquid in 1991). The toric code can also be considered to be a Z2 lattice gauge theory in a particular limit. It was introduced by Alexei Kitaev.

Dynamical mean-field theory (DMFT) is a method to determine the electronic structure of strongly correlated materials. In such materials, the approximation of independent electrons, which is used in density functional theory and usual band structure calculations, breaks down. Dynamical mean-field theory, a non-perturbative treatment of local interactions between electrons, bridges the gap between the nearly free electron gas limit and the atomic limit of condensed-matter physics.

In condensed matter physics, an AKLT model, also known as an Affleck-Kennedy-Lieb-Tasaki model is an extension of the one-dimensional quantum Heisenberg spin model. The proposal and exact solution of this model by Ian Affleck, Elliott H. Lieb, Tom Kennedy and Hal Tasaki provided crucial insight into the physics of the spin-1 Heisenberg chain. It has also served as a useful example for such concepts as valence bond solid order, symmetry-protected topological order and matrix product state wavefunctions.

The Rashba effect, also called Bychkov–Rashba effect, is a momentum-dependent splitting of spin bands in bulk crystals and low-dimensional condensed matter systems similar to the splitting of particles and anti-particles in the Dirac Hamiltonian. The splitting is a combined effect of spin–orbit interaction and asymmetry of the crystal potential, in particular in the direction perpendicular to the two-dimensional plane. This effect is named in honour of Emmanuel Rashba, who discovered it with Valentin I. Sheka in 1959 for three-dimensional systems and afterward with Yurii A. Bychkov in 1984 for two-dimensional systems.

Symmetry-protected topological (SPT) order is a kind of order in zero-temperature quantum-mechanical states of matter that have a symmetry and a finite energy gap.

The eigenstate thermalization hypothesis is a set of ideas which purports to explain when and why an isolated quantum mechanical system can be accurately described using equilibrium statistical mechanics. In particular, it is devoted to understanding how systems which are initially prepared in far-from-equilibrium states can evolve in time to a state which appears to be in thermal equilibrium. The phrase "eigenstate thermalization" was first coined by Mark Srednicki in 1994, after similar ideas had been introduced by Josh Deutsch in 1991. The principal philosophy underlying the eigenstate thermalization hypothesis is that instead of explaining the ergodicity of a thermodynamic system through the mechanism of dynamical chaos, as is done in classical mechanics, one should instead examine the properties of matrix elements of observable quantities in individual energy eigenstates of the system.

A Matrix product state (MPS) is a quantum state of many particles, written in the following form:

Many-body localization (MBL) is a dynamical phenomenon occurring in isolated many-body quantum systems. It is characterized by the system failing to reach thermal equilibrium, and retaining a memory of its initial condition in local observables for infinite times.

Exact diagonalization (ED) is a numerical technique used in physics to determine the eigenstates and energy eigenvalues of a quantum Hamiltonian. In this technique, a Hamiltonian for a discrete, finite system is expressed in matrix form and diagonalized using a computer. Exact diagonalization is only feasible for systems with a few tens of particles, due to the exponential growth of the Hilbert space dimension with the size of the quantum system. It is frequently employed to study lattice models, including the Hubbard model, Ising model, Heisenberg model, t-J model, and SYK model.

The Dicke model is a fundamental model of quantum optics, which describes the interaction between light and matter. In the Dicke model, the light component is described as a single quantum mode, while the matter is described as a set of two-level systems. When the coupling between the light and matter crosses a critical value, the Dicke model shows a mean-field phase transition to a superradiant phase. This transition belongs to the Ising universality class and was realized in cavity quantum electrodynamics experiments. Although the superradiant transition bears some analogy with the lasing instability, these two transitions belong to different universality classes.