Reason is the capacity of applying logic consciously by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, science, language, mathematics, and art, and is normally considered to be a distinguishing ability possessed by humans. Reason is sometimes referred to as rationality.

A fallacy, is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument that may appear to be well-reasoned if unnoticed. The term was introduced in the Western intellectual tradition by the Aristotelian De Sophisticis Elenchis.

Abductive reasoning is a form of logical inference that seeks the simplest and most likely conclusion from a set of observations. It was formulated and advanced by American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce beginning in the latter half of the 19th century.

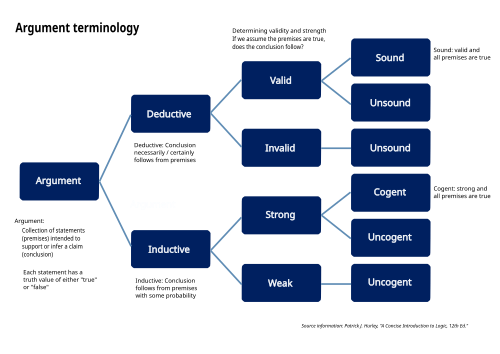

Deductive reasoning is the mental process of drawing deductive inferences. An inference is deductively valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, i.e. it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.

First formulated by David Hume, the problem of induction questions our reasons for believing that the future will resemble the past, or more broadly it questions predictions about unobserved things based on previous observations. This inference from the observed to the unobserved is known as "inductive inferences". Hume, while acknowledging that everyone does and must make such inferences, argued that there is no non-circular way to justify them, thereby undermining one of the Enlightenment pillars of rationality.

Inferences are steps in reasoning, moving from premises to logical consequences; etymologically, the word infer means to "carry forward". Inference is theoretically traditionally divided into deduction and induction, a distinction that in Europe dates at least to Aristotle. Deduction is inference deriving logical conclusions from premises known or assumed to be true, with the laws of valid inference being studied in logic. Induction is inference from particular evidence to a universal conclusion. A third type of inference is sometimes distinguished, notably by Charles Sanders Peirce, contradistinguishing abduction from induction.

The term Inductive reasoning is used to refer to any method of reasoning in which broad generalizations or principles are derived from a body of observations. This article is concerned with the inductive reasoning other than deductive reasoning, where the conclusion of a deductive argument is certain given the premises are correct; in contrast, the truth of the conclusion of an inductive argument is at best probable, based upon the evidence given.

Logical reasoning is a mental activity that aims to arrive at a conclusion in a rigorous way. It happens in the form of inferences or arguments by starting from a set of premises and reasoning to a conclusion supported by these premises. The premises and the conclusion are propositions, i.e. true or false claims about what is the case. Together, they form an argument. Logical reasoning is norm-governed in the sense that it aims to formulate correct arguments that any rational person would find convincing. The main discipline studying logical reasoning is logic.

A statistical syllogism is a non-deductive syllogism. It argues, using inductive reasoning, from a generalization true for the most part to a particular case.

In philosophy of logic, defeasible reasoning is a kind of provisional reasoning that is rationally compelling, though not deductively valid. It usually occurs when a rule is given, but there may be specific exceptions to the rule, or subclasses that are subject to a different rule. Defeasibility is found in literatures that are concerned with argument and the process of argument, or heuristic reasoning.

In logic, the logical form of a statement is a precisely-specified semantic version of that statement in a formal system. Informally, the logical form attempts to formalize a possibly ambiguous statement into a statement with a precise, unambiguous logical interpretation with respect to a formal system. In an ideal formal language, the meaning of a logical form can be determined unambiguously from syntax alone. Logical forms are semantic, not syntactic constructs; therefore, there may be more than one string that represents the same logical form in a given language.

In logic and philosophy, a formal fallacy, deductive fallacy, logical fallacy or non sequitur is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system, for example propositional logic. It is defined as a deductive argument that is invalid. The argument itself could have true premises, but still have a false conclusion. Thus, a formal fallacy is a fallacy where deduction goes wrong, and is no longer a logical process. This may not affect the truth of the conclusion, since validity and truth are separate in formal logic.

Logic is the formal science of using reason and is considered a branch of both philosophy and mathematics and to a lesser extent computer science. Logic investigates and classifies the structure of statements and arguments, both through the study of formal systems of inference and the study of arguments in natural language. The scope of logic can therefore be very large, ranging from core topics such as the study of fallacies and paradoxes, to specialized analyses of reasoning such as probability, correct reasoning, and arguments involving causality. One of the aims of logic is to identify the correct and incorrect inferences. Logicians study the criteria for the evaluation of arguments.

Appeal to the stone, also known as argumentum ad lapidem, is a logical fallacy that dismisses an argument as untrue or absurd. The dismissal is made by stating or reiterating that the argument is absurd, without providing further argumentation. This theory is closely tied to proof by assertion due to the lack of evidence behind the statement and its attempt to persuade without providing any evidence.

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persuasion.

The psychology of reasoning is the study of how people reason, often broadly defined as the process of drawing conclusions to inform how people solve problems and make decisions. It overlaps with psychology, philosophy, linguistics, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, logic, and probability theory.

Philosophy of logic is the area of philosophy that studies the scope and nature of logic. It investigates the philosophical problems raised by logic, such as the presuppositions often implicitly at work in theories of logic and in their application. This involves questions about how logic is to be defined and how different logical systems are connected to each other. It includes the study of the nature of the fundamental concepts used by logic and the relation of logic to other disciplines. According to a common characterisation, philosophical logic is the part of the philosophy of logic that studies the application of logical methods to philosophical problems, often in the form of extended logical systems like modal logic. But other theorists draw the distinction between the philosophy of logic and philosophical logic differently or not at all. Metalogic is closely related to the philosophy of logic as the discipline investigating the properties of formal logical systems, like consistency and completeness.

World disclosure refers to how things become intelligible and meaningfully relevant to human beings, by virtue of being part of an ontological world – i.e., a pre-interpreted and holistically structured background of meaning. This understanding is said to be first disclosed to human beings through their practical day-to-day encounters with others, with things in the world, and through language.

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It studies how conclusions follow from premises due to the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content. Informal logic is associated with informal fallacies, critical thinking, and argumentation theory. It examines arguments expressed in natural language while formal logic uses formal language. When used as a countable noun, the term "a logic" refers to a logical formal system that articulates a proof system. Logic plays a central role in many fields, such as philosophy, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics.