Winners and losers

Fishman says that the London Conference was "an extraordinarily successful conference" because it "provided the institutional framework through which the leading powers of the time safeguarded the peace of Europe". [2] G. M. Trevelyan from a British standpoint called it "one of the most beneficent and difficult feats ever accomplished by our diplomacy"; [3] while the French too saw their goal of an independent Belgium, which was peacefully accepted by the other Great Powers, as being achieved. [4]

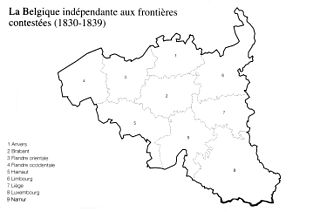

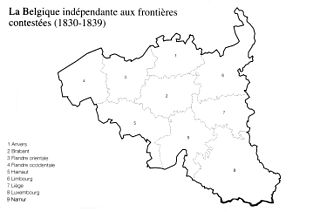

However, historians of both Belgium and the Netherlands have largely ignored it. Dutch historians see it as their nadir in the 19th century, for the loss of the southern territories shook the nation's confidence. Belgian historians see the result not as a victory, says Fishman, but as a frustrating and humiliating experience, involving the loss of territory in Luxemburg and Limburg under the settlement terms, in which the great powers allowed Belgium to come into existence. [5] [6]

The history of the Netherlands extends back long before the founding of the modern Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 after the defeat of Napoleon. For thousands of years, people have been living together around the river deltas of this section of the North Sea coast. Records begin with the four centuries during which the region formed a militarized border zone of the Roman Empire. As the Western Roman Empire collapsed and the Middle Ages began, three dominant Germanic peoples coalesced in the area – Frisians in the north and coastal areas, Low Saxons in the northeast, in addition to the Franks in the south. By 800, the Frankish Carolingian dynasty had once again integrated the area into an empire covering a large part of Western Europe. The region was part of the duchy of Lower Lotharingia within the Holy Roman Empire, but neither the empire nor the duchy were governed in a centralized manner. For several centuries, medieval lordships such as Brabant, Holland, Zeeland, Friesland, Guelders and others held a changing patchwork of territories.

For most of its history, what is now Belgium was either a part of a larger territory, such as the Carolingian Empire, or divided into a number of smaller states, prominent among them being the Duchy of Brabant, the County of Flanders, the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, the County of Namur, the County of Hainaut and the County of Luxembourg. Due to its strategic location as a country of contact between different cultures, Belgium has been called the "crossroads of Europe"; for the many armies fighting on its soil, it has also been called the "battlefield of Europe" or the "cockpit of Europe".

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed between 1815 and 1830. The United Netherlands was created in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars through the fusion of territories that had belonged to the former Dutch Republic, Austrian Netherlands, and Prince-Bishopric of Liège in order to form a buffer state between the major European powers. The polity was a constitutional monarchy, ruled by William I of the House of Orange-Nassau.

Leopold I was the first King of the Belgians, reigning from 21 July 1831 until his death in 1865.

The Concert of Europe was a general agreement among the great powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying for position and influence, the Concert was an extended period of relative peace and stability in Europe following the Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars which had consumed the continent since the 1790s. There is considerable scholarly dispute over the exact nature and duration of the Concert. Some scholars argue that it fell apart nearly as soon as it began in the 1820s when the great powers disagreed over the handling of liberal revolts in Italy, while others argue that it lasted until the outbreak of World War I and others for points in between. For those arguing for a longer duration, there is generally agreement that the period after the Revolutions of 1848 and the Crimean War (1853–1856) represented a different phase with different dynamics than the earlier period.

The Treaty of London of 1839, was signed on 19 April 1839 between the Concert of Europe, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Belgium. It was a direct follow-up to the 1831 Treaty of the XVIII Articles, which the Netherlands had refused to sign, and the result of negotiations at the London Conference of 1838–1839.

Greater Netherlands is an irredentist concept which unites the Netherlands, Flanders, and sometimes Brussels. Additionally, a Greater Netherlands state may include the annexation of the French Westhoek, Suriname, formerly Dutch-speaking areas of Germany and France, or even the ethnically Dutch and/or Afrikaans-speaking parts of South Africa. A related proposal is the Pan-Netherlands concept, which includes Wallonia and potentially also Luxembourg.

The Belgian Revolution was the conflict which led to the secession of the southern provinces from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

The Revolutions of 1830 were a revolutionary wave in Europe which took place in 1830. It included two "romantic nationalist" revolutions, the Belgian Revolution in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the July Revolution in France along with rebellions in Congress Poland, Italian states, Portugal and Switzerland. It was followed eighteen years later, by another and much stronger wave of revolutions known as the Revolutions of 1848.

The Flahaut partition plan for Belgium was a proposal developed in 1830 at the London Conference of 1830 by the French diplomat Charles de Flahaut, to partition Belgium. The proposal was immediately rejected by the French Foreign Ministry upon Charles Maurice de Talleyrand's insistence.

The Treaty of the Eighteen Articles was a proposal for a treaty between Belgium and the Netherlands to establish borders between the two countries.

Belgium–United Kingdom relations are foreign relations between Belgium and the United Kingdom. Belgium has an embassy in London and 8 honorary consulates. The United Kingdom has an embassy in Brussels.

The United States and Belgium maintain a friendly bilateral relationship. Continuing to celebrate cooperative U.S. and Belgian relations, 2007 marked the 175th anniversary of the nations' relationship.

The history of Belgium in World War I traces Belgium's role between the German invasion in 1914, through the continued military resistance and occupation of the territory by German forces to the armistice in 1918, as well as the role it played in the international war effort through its African colony and small force on the Eastern Front.

This article covers worldwide diplomacy and, more generally, the international relations of the great powers from 1814 to 1919. This era covers the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815), to the end of the First World War and the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920).

In the history of Belgium, the period from 1789 to 1914, dubbed the "long 19th century" by the historian Eric Hobsbawm, includes the end of Austrian rule and periods of French and Dutch rule over the region, leading to the creation of the first independent Belgian state in 1830.

The Netherlands remained neutral during World War I, a stance that arose partly from a strict policy of neutrality in international affairs that started in 1830, with the secession of Belgium from the Netherlands. Dutch neutrality was not guaranteed by the major powers in Europe and was not part of the Dutch constitution. The country's neutrality was based on the belief that its strategic position between the German Empire, German-occupied Belgium, and the British guaranteed its safety.

As of 2018, Wolters Kluwer ranks as the Dutch biggest publisher of books in terms of revenue. Other notable Dutch houses include Brill and Elsevier.

Horst Lademacher is a German historian specializing in the history of the Netherlands. He was a professor of modern history at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, University of Kassel and the University of Münster. At the latter institute he was also director of the Zentrum für Niederlande-Studien from 1990 to 2000.

The Declaration of Sainte-Adresse was a diplomatic announcement made on 14 February 1916 by the principal Allied powers of the First World War. It was also supported by Italy and Japan. The declaration stated that the powers would refuse to sign any peace treaty ending the war that left Belgium, a neutral power at the war's start, without "political and economic independence". It was extended in April 1916 to also cover the Belgian Congo.