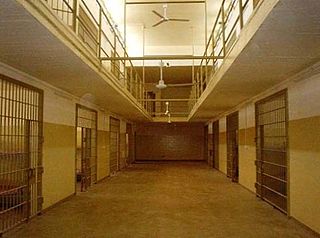

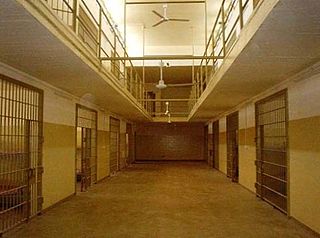

Abu Ghraib prison was a prison complex in Abu Ghraib, Iraq, located 32 kilometers (20 mi) west of Baghdad. Abu Ghraib prison was opened in the 1950s and served as a maximum-security prison. From the 1970s, the prison was used by Saddam Hussein to hold political prisoners and later the United States to hold Iraqi prisoners. It developed a reputation for torture and extrajudicial killing, and was closed in 2014.

Janis Leigh Karpinski is a retired career officer in the United States Army Reserve. She is notable for having commanded the forces that operated Abu Ghraib and other prisons in Iraq in 2003 and 2004, at the time of the scandal related to torture and prisoner abuse. She commanded three prisons in Iraq and the forces that ran them. Her education includes a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and secondary education from Kean College, a Master of Arts degree in aviation management from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, and a Master of Arts in strategic studies from the United States Army War College.

Charles A. Graner Jr. is a former American soldier and convicted war criminal who was court-martialed for prisoner abuse after the 2003–2004 Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal. Along with other soldiers of his Army Reserve unit, the 372nd Military Police Company, Graner was accused of allowing and inflicting sexual, physical, and psychological abuse on Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib prison, a notorious prison in Baghdad during the United States' occupation of Iraq.

Sabrina D. Harman is a former American soldier and convicted war criminal who was court-martialed by the United States Army for prisoner abuse after the 2003–2004 Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal. Along with other soldiers of her Army Reserve unit, the 372nd Military Police Company, she was accused of allowing and inflicting physical and psychological abuse on Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib prison, a notorious prison in Baghdad during the United States' occupation of Iraq.

Jeremy Charles Sivits was a United States Army reservist. He was one of several soldiers charged and convicted by the U.S. Army in connection with the 2003–2004 Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal in Baghdad, Iraq, during and after the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Sivits was a member of the 372nd Military Police Company during this time.

Megan Ambuhl is a former United States Army Reserve soldier who was convicted of dereliction of duty for her role in the prisoner abuse that occurred at Abu Ghraib prison, a notorious prison in Baghdad during the United States' occupation of Iraq.

Ivan "Chip" Frederick II is a former American soldier and convicted war criminal. He was court-martialed for prisoner abuse after the 2003–2004 Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal. Along with other soldiers of his Army Reserve unit, the 372nd Military Police Company, Frederick was accused of allowing and inflicting sexual, physical, and psychological abuse on Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib prison, a notorious prison in Baghdad during the United States' occupation of Iraq. In May 2004, Frederick pleaded guilty to conspiracy, dereliction of duty, maltreatment of detainees, assault, and indecent acts. He was sentenced to 8 years' confinement and loss of rank and pay, and he received a dishonorable discharge. He was released on parole in October 2007, after spending four years in prison.

During the early stages of the Iraq War, members of the United States Army and the Central Intelligence Agency committed a series of human rights violations and war crimes against detainees in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, including physical abuse, sexual humiliation, physical and psychological torture, and rape, as well as the killing of Manadel al-Jamadi and the desecration of his body. The abuses came to public attention with the publication of photographs of the abuse by CBS News in April 2004. The incidents caused shock and outrage, receiving widespread condemnation within the United States and internationally.

About six months after the United States invasion of Iraq of 2003, rumors of Iraq prison abuse scandals started to emerge.

The Taguba Report, officially titled US Army 15-6 Report of Abuse of Prisoners in Iraq, is a report published in May 2004 containing the findings from an official military inquiry into the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse. It is named after Major General Antonio Taguba, the report's principal author.

Steven Anthony Stefanowicz was involved, as a private contractor for CACI International, in the interrogations at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

Sergeant Joseph M. Darby is a former U.S. Army Reservist known as the whistleblower in the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse scandal. Darby is a graduate of North Star High School, near his hometown at the time, Jenners, Pennsylvania.

Manadel al-Jamadi was an Iraqi national who was killed in United States custody during a CIA interrogation at Abu Ghraib prison on 4 November 2003. His name became known in 2004 when the Abu Ghraib scandal made headlines; his corpse packed in ice was the background for widely reprinted photographs of grinning U.S. Army specialists Sabrina Harman and Charles Graner each offering a "thumbs-up" gesture. Al-Jamadi had been a suspect in a bomb attack that killed 34 people, including one US soldier, and left more than 200 wounded in a Baghdad Red Cross facility.

In 2005, The New York Times obtained a 2,000-page United States Army investigatory report concerning the homicides of two unarmed civilian Afghan prisoners by U.S. military personnel in December 2002 at the Bagram Theater Internment Facility in Bagram, Afghanistan and general treatment of prisoners. The two prisoners, Habibullah and Dilawar, were repeatedly chained to the ceiling and beaten, resulting in their deaths. Military coroners ruled that both the prisoners' deaths were homicides. Autopsies revealed severe trauma to both prisoners' legs, describing the trauma as comparable to being run over by a bus. Seven soldiers were charged in 2005.

United States Army Captain Carolyn Wood is a military intelligence officer who served in both Afghanistan and Iraq. She was implicated by the Fay Report to have "failed" in several aspects of her command regarding her oversight of interrogators at Abu Ghraib. She was alleged by Amnesty International to be centrally involved in the 2003 Abu Ghraib and 2002 Bagram prisoner abuse cases. Wood is featured in the 2008 Academy award-winning documentary Taxi to the Dark Side.

The 372nd Military Police Company is Military Police Corps unit of the United States Army Reserve. It is based out of Cresaptown, Maryland. Eleven former members of the unit were charged and found guilty of war crimes in connection to the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse scandal during the Iraq War. Another member of the unit, Joe Darby, was awarded the Profile in Courage Award by the Kennedy family for exposing the prisoner abuse. The unit is credited with the capture and stabilization of the city of Hillah along with the 1st Marine Regiment. It was also responsible for guarding main supply routes used by American forces in Iraq.

The Fay Report, officially titled Investigation of Intelligence Activities at Abu Ghraib, was a military investigation into the torture and abuse of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. It was sparked by leaked images of Iraqi prisoners, hooded and naked, being mistreated obtained by the United States and global media in April 2004. The Fay Report was one of five such investigations ordered by the military and was the third to be submitted, as it was completed and released on August 25, 2004. Prior to the report's release, seven reservist military police had already been charged for their roles in the abuse at the prison, and so the report examined the role of military intelligence, specifically the 205th Military Intelligence Brigade that was responsible for the interrogation of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. General Paul J. Kern was the appointing authority for the report and oversaw the investigation. The chief investigators were Major General George Fay, whom the report is named after, and Lieutenant General Anthony R. Jones.

Steven L. Jordan is a former United States Army Reserve officer. Jordan volunteered to return to active duty to support the war in Iraq, and as a civil affairs officer with a background in military intelligence, was made the director of the Joint Interrogation Debriefing Center at Abu Ghraib prison.

A number of incidents stemming from the September 11 attacks have raised questions about legality.

Standard Operating Procedure is a 2008 American documentary film written and directed by Errol Morris that explores the meaning of the photographs taken by U.S. military police at the Abu Ghraib prison in late 2003, the content of which revealed the torture and abuse of its prisoners by U.S. soldiers and subsequently resulted in a public scandal.