In mathematics, a diffeomorphism is an isomorphism of smooth manifolds. It is an invertible function that maps one differentiable manifold to another such that both the function and its inverse are continuously differentiable.

In the mathematical field of topology, a homeomorphism, also called topological isomorphism, or bicontinuous function, is a bijective and continuous function between topological spaces that has a continuous inverse function. Homeomorphisms are the isomorphisms in the category of topological spaces—that is, they are the mappings that preserve all the topological properties of a given space. Two spaces with a homeomorphism between them are called homeomorphic, and from a topological viewpoint they are the same.

In mathematics, an isomorphism is a structure-preserving mapping between two structures of the same type that can be reversed by an inverse mapping. Two mathematical structures are isomorphic if an isomorphism exists between them. The word isomorphism is derived from the Ancient Greek: ἴσοςisos "equal", and μορφήmorphe "form" or "shape".

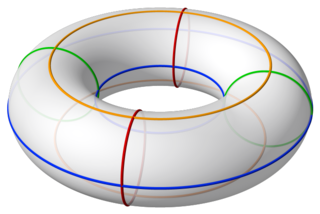

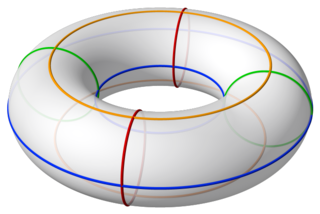

In geometry, a torus is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space one full revolution about an axis that is coplanar with the circle. The main types of toruses include ring toruses, horn toruses, and spindle toruses. A ring torus is sometimes colloquially referred to as a donut or doughnut.

In mathematics, homology is a general way of associating a sequence of algebraic objects, such as abelian groups or modules, with other mathematical objects such as topological spaces. Homology groups were originally defined in algebraic topology. Similar constructions are available in a wide variety of other contexts, such as abstract algebra, groups, Lie algebras, Galois theory, and algebraic geometry.

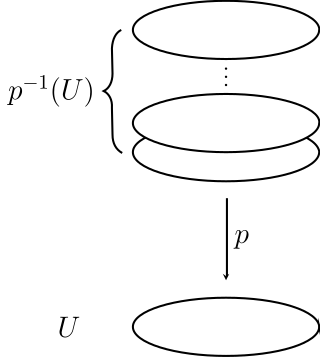

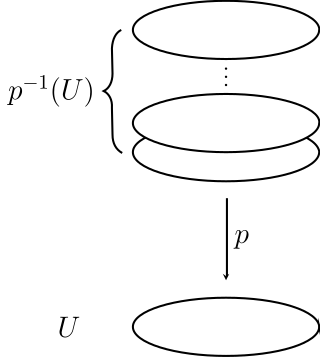

In topology, a covering or covering projection is a surjective map between topological spaces that, intuitively, locally acts like a projection of multiple copies of a space onto itself. In particular, coverings are special types of local homeomorphisms. If is a covering, is said to be a covering space or cover of , and is said to be the base of the covering, or simply the base. By abuse of terminology, and may sometimes be called covering spaces as well. Since coverings are local homeomorphisms, a covering space is a special kind of étale space.

In geometric topology, a field within mathematics, the obstruction to a homotopy equivalence of finite CW-complexes being a simple homotopy equivalence is its Whitehead torsion which is an element in the Whitehead group. These concepts are named after the mathematician J. H. C. Whitehead.

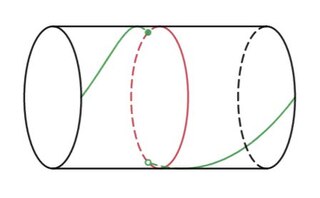

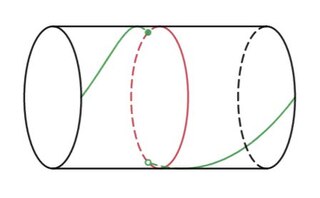

In geometric topology, a branch of mathematics, a Dehn twist is a certain type of self-homeomorphism of a surface.

In mathematics, complex cobordism is a generalized cohomology theory related to cobordism of manifolds. Its spectrum is denoted by MU. It is an exceptionally powerful cohomology theory, but can be quite hard to compute, so often instead of using it directly one uses some slightly weaker theories derived from it, such as Brown–Peterson cohomology or Morava K-theory, that are easier to compute.

In mathematics, particularly topology, the homeomorphism group of a topological space is the group consisting of all homeomorphisms from the space to itself with function composition as the group operation. Homeomorphism groups are very important in the theory of topological spaces and in general are examples of automorphism groups. Homeomorphism groups are topological invariants in the sense that the homeomorphism groups of homeomorphic topological spaces are isomorphic as groups.

In mathematics, the Teichmüller space of a (real) topological surface is a space that parametrizes complex structures on up to the action of homeomorphisms that are isotopic to the identity homeomorphism. Teichmüller spaces are named after Oswald Teichmüller.

In mathematics, a Hilbert manifold is a manifold modeled on Hilbert spaces. Thus it is a separable Hausdorff space in which each point has a neighbourhood homeomorphic to an infinite dimensional Hilbert space. The concept of a Hilbert manifold provides a possibility of extending the theory of manifolds to infinite-dimensional setting. Analogously to the finite-dimensional situation, one can define a differentiable Hilbert manifold by considering a maximal atlas in which the transition maps are differentiable.

In algebraic topology, an area of mathematics, a homeotopy group of a topological space is a homotopy group of the group of self-homeomorphisms of that space.

In 4-dimensional topology, a branch of mathematics, Rokhlin's theorem states that if a smooth, orientable, closed 4-manifold M has a spin structure, then the signature of its intersection form, a quadratic form on the second cohomology group , is divisible by 16. The theorem is named for Vladimir Rokhlin, who proved it in 1952.

In linear algebra, particularly projective geometry, a semilinear map between vector spaces V and W over a field K is a function that is a linear map "up to a twist", hence semi-linear, where "twist" means "field automorphism of K". Explicitly, it is a function T : V → W that is:

In mathematics, and more precisely in topology, the mapping class group of a surface, sometimes called the modular group or Teichmüller modular group, is the group of homeomorphisms of the surface viewed up to continuous deformation. It is of fundamental importance for the study of 3-manifolds via their embedded surfaces and is also studied in algebraic geometry in relation to moduli problems for curves.

In homotopy theory, a branch of mathematics, the Barratt–Priddy theorem expresses a connection between the homology of the symmetric groups and mapping spaces of spheres. The theorem is also often stated as a relation between the sphere spectrum and the classifying spaces of the symmetric groups via Quillen's plus construction.

This is a glossary of properties and concepts in algebraic topology in mathematics.

In mathematics, a configuration space is a construction closely related to state spaces or phase spaces in physics. In physics, these are used to describe the state of a whole system as a single point in a high-dimensional space. In mathematics, they are used to describe assignments of a collection of points to positions in a topological space. More specifically, configuration spaces in mathematics are particular examples of configuration spaces in physics in the particular case of several non-colliding particles.

In mathematics, the automorphism group of an object X is the group consisting of automorphisms of X under composition of morphisms. For example, if X is a finite-dimensional vector space, then the automorphism group of X is the group of invertible linear transformations from X to itself. If instead X is a group, then its automorphism group is the group consisting of all group automorphisms of X.