The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire on the Indian subcontinent which existed from the early 4th century CE to early 6th century CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. This period has been considered as the Golden Age of India by historians, although this characterisation has been disputed by some other historians. The ruling dynasty of the empire was founded by Gupta and the most notable rulers of the dynasty were Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, Chandragupta II, Kumaragupta I and Skandagupta.

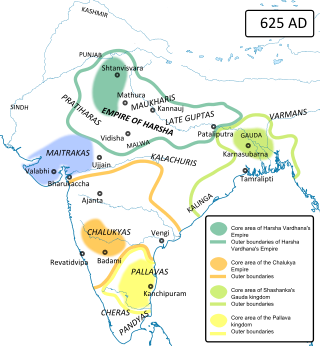

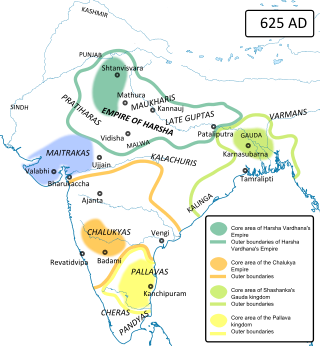

Harshavardhana was a Pushyabhuti emperor who ruled northern India from 606 to 647 CE. He was the son of Prabhakaravardhana who had defeated the Alchon Hun invaders, and the younger brother of Rajyavardhana, a king of Thanesar, present-day Haryana.

Mihirakula, sometimes referred to as Mihiragula or Mahiragula, was the second and last Alchon Hun king of northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent between 502 and 530 CE. He was a son of and successor to Toramana of Huna heritage. His father ruled the Indian part of the Hephthalite Empire. Mihirakula ruled from his capital of Sagala.

Toramana also called Toramana Shahi Jauvla was a king of the Alchon Huns who ruled in northern India in the late 5th and the early 6th century CE. Toramana consolidated the Alchon power in Punjab, and conquered northern and central India including Eran in Madhya Pradesh. Toramana used the title "Great King of Kings", equivalent to "Emperor", in his inscriptions, such as the Eran boar inscription.

Prabhakaravardhana was a king of Thanesar in northern India around the time of the decline of the Gupta Empire. According to the historian R. C. Majumdar, he was the first notable king of the Vardhana dynasty but the fourth ruler from the family, who are also referred to as the Pushpabhutis. He had been preceded by his father, Adityavardhana, grandfather Rajyavardhana I and great-grandfather, Naravardhana, but inscriptions suggest that Banabhatta, the seventh-century bard and chronicler of the Vardhanas, may have been wrong to call these earlier rulers kings and that they may instead have been mere feudatory rulers of minor significance.

The Pushyabhuti dynasty, also known as the Vardhana dynasty, was the ruling dynasty of the Kingdom of Thanesar and the Kannauj Empire in northern India during the 6th and 7th centuries. The dynasty reached its zenith under its last ruler Harsha Vardhana, whose empire covered much of north and north-western India, extending till Kamarupa in the east and Narmada River in the south. The dynasty initially ruled from Sthanveshvara, but Harsha eventually made Kanyakubja his capital, from where he ruled until 647 CE.

The Later Gupta dynasty ruled Magadha in eastern India between the 6th and 8th centuries CE. The Later Guptas succeeded the Imperial Guptas as the rulers of eastern Malwa or Magadha, but there is no evidence connecting the two dynasties; these appear to be two distinct families. The "Later Guptas" are so-called because the names of their rulers ended with the suffix "-gupta", which they might have adopted to portray themselves as the successors of the Imperial Guptas.

Bhanugupta was one of the lesser known kings of the Gupta dynasty. He is only known from an inscription in Eran, and a mention in the Manjushri-mula-kalpa.

The Alchon Huns, also known as the Alkhan, Alchono, Alxon, Alkhon, Alakhana, and Walxon, were a nomadic people who established states in Central Asia and South Asia during the 4th and 6th centuries CE. They were first mentioned as being located in Paropamisus, and later expanded south-east, into the Punjab and Central India, as far as Eran and Kausambi. The Alchon invasion of the Indian subcontinent eradicated the Kidarite Huns who had preceded them by about a century, and contributed to the fall of the Gupta Empire, in a sense bringing an end to Classical India.

Adityavardhana was a king of Thanesar in northern India around the time of the decline of the Gupta Empire. He was the third ruler of the Pushyabhuti dynasty, and father of Prabhakaravardhana. Adityavardhana's father was Rajyavardhana I and his grandfather, Naravardhana, the founder of the Srikantha dynasty of Tanesar.

The Vadathika Cave Inscription, also called the Nagarjuni Hill Cave Inscription of Anantavarman, is a 5th- or 6th-century CE Sanskrit inscriptions in Gupta script found in the Nagarjuni hill cave of the Barabar Caves group in Gaya district Bihar. The inscription is notable for including symbol for Om in Gupta era. It marks the dedication of the cave to a statue of Bhutapati (Shiva) and Devi (Parvati). The statue was likely of Ardhanarishvara that was missing when the caves came to the attention of archaeologists in the 18th-century.

The Panduvamshis or Pandavas were an Indian dynasty that ruled the historical Dakshina Kosala region in present-day Chhattisgarh state of India, during the 7th and the 8th centuries. They may have been related to the earlier Panduvamshis of Mekala: both dynasties claimed lunar lineage and descent from the legendary Pandavas.

The Second Aulikara dynasty was a royal dynasty that ruled over the Malwa plateau, and at its peak under Yashodharman Vishnuvardhana controlled a vast area, consisting of almost all of Northern India and parts of Deccan plateau. It was the second royal house of the Aulikara clan.

Hari-varman was the founder of the Maukhari dynasty. He is the first ruler to be named in the known Maukhari records.

Iśanavarman was the first independent Maukhari ruler of Kannauj. He was a very powerful king, and adopted the title of Maharajadhiraja.

Sharvavarman was the Maukhari ruler of Kanyakubja from circa 560-575 CE and held the title of "Mahārājādhirāja", "King of Kings" i.e. "Emperor".

The Aphsad inscription of Ādityasena is an Indian inscription from the reign of the Later Gupta dynasty king Aditya-sena. The inscription was found in 1880 by Markham Kittoe in the village of Apasadha, Bihar, and is now located in the British Museum.

The Gauda–Gupta War was a conflict between Gopachandra on one side with Ishanavarman and Jivitagupta I on the other side. The war resulted in the defeat of the Gauda Kingdom.

The emergence of the Great Kushans in Bactria and Northwestern India during the first century CE reshaped the geopolitical landscape of the region, impacting trade routes, international politics, and regional power dynamics. Economically, the Kushans served as intermediaries in trade, controlling crucial sections of the Silk Road and redirecting trade between China, India, and the eastern countries away from Parthian territory. This posed a significant economic challenge to the Parthians and positioned the Kushans as major players in international trade. Politically, the rise of the Kushans had profound implications for Iran, as it found itself sandwiched between the Roman Empire and the Kushans. The Romans recognized the strategic importance of the Kushan Empire and sought direct relations with its rulers to safeguard trade routes between Rome, China, and India. This geopolitical scenario led the early Sasanians to prioritize the conquest of the Kushan empire in their Eastern policy, eventually achieving remarkable success under Emperor Ardashir I. Following the decline of the Great Kushans, remnants known as the "Little Kushans" persisted in the Punjab region, eventually being subjugated by the Gupta Empire under Samudragupta. His inscription on the Allahabad pillar illustrates Gupta dominance over the last Kushan rulers, who were forced to accept Gupta suzerainty. Samudragupta's strategic alliances and military campaigns against the Sassanians and other regional powers solidified Gupta control over large parts of the Indian subcontinent. However, the Gupta Empire faced various challenges, including incursions by the Hunas, who posed a considerable threat to neighboring civilizations. Skandagupta's leadership and military strategy were crucial in resisting Huna advances, although the extent of damage caused by their invasions remains debated among scholars. Despite facing external pressures, internal succession issues within the Gupta dynasty, such as the question of rightful heirs, also contributed to the complexities of governance during that time.

The Second Hunnic War commenced with Mihirakula's ascension to power in West Punjab around 515 AD, succeeding his father, Toramana. Initially, Mihirakula's authority seemed lesser compared to his father's, as indicated by numismatic evidence. In 520, Song Yun encountered the "King of the Huns" along the Jhelum River, where the Northern Wei envoy depicted him as having a violent demeanor and being responsible for massacres, resulting in an unpleasant meeting.

![]() , Mau-kha-ri) was a post-Gupta dynasty who controlled the vast plains of Ganga-Yamuna for over six generations from their capital at Kanyakubja. They earlier served as vassals of the Guptas and later of Harsha's Vardhana dynasty. The Maukharis established their independence during the mid 6th century. The dynasty ruled over much of Uttar Pradesh and Magadha. Around 606 CE, a large area of their empire was reconquered by the Later Guptas. [3] According to Hieun-Tsang, the territory may have been lost to King Shashanka of the Gauda Kingdom, who declared independence circa 600CE. [4] [5]

, Mau-kha-ri) was a post-Gupta dynasty who controlled the vast plains of Ganga-Yamuna for over six generations from their capital at Kanyakubja. They earlier served as vassals of the Guptas and later of Harsha's Vardhana dynasty. The Maukharis established their independence during the mid 6th century. The dynasty ruled over much of Uttar Pradesh and Magadha. Around 606 CE, a large area of their empire was reconquered by the Later Guptas. [3] According to Hieun-Tsang, the territory may have been lost to King Shashanka of the Gauda Kingdom, who declared independence circa 600CE. [4] [5]