Career

In 2012, Inequality and poverty researcher Tony Atkinson hired Roser at the University of Oxford where he collaborated with Piketty, Morelli, and Atkinson. [8] In 2015, he established a research team at the University of Oxford which is studying global development. [9]

He founded Our World In Data, a scientific web publication with the goal to present "research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems." [10] During the first years he financed his project by working as a bicycle tour guide around Europe. [11]

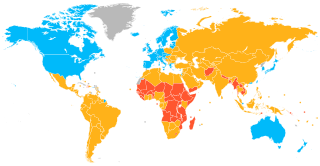

Our World In Data covers a range of aspects of development: global health, food provision, the growth and distribution of incomes, violence, rights, wars, technology, education, and environmental changes, among others. The publication makes use of data visualisations which are licensed under Creative Commons and are widely used in research, in the media, and as teaching material. [12]

In 2019 he worked with Y Combinator on Our World in Data. [13]

Motivation

Roser has said that global poverty, inequality, existential risks, human rights abuse, and humanity's environmental impact are among the world's most severe problems. [1] [14]

About his motivation for this work he wrote "The mission of this work has never changed: from the first days in 2011 Our World in Data focussed on the big global problems and asked how it is possible to make progress against them. The enemies of this effort were also always the same: apathy and cynicism." [15] He said that "it is because the world is terrible still that it is so important to write about how the world became a better place." [16]

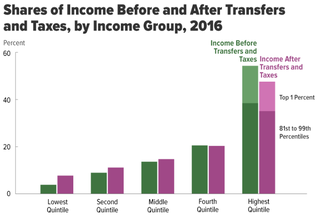

He is critical of the mass media's excessive focus on single events which he claims is not helpful in understanding "the long-lasting, forceful changes that reshape our world, as well as the large, long-standing problems that continue to confront us." [1] [17] [18] In contrast to the event-focussed reporting of the news media Roser advocates the adoption of a broader perspective on global change, and in particular a focus on those living in poverty. [18] The focus on the upper classes, especially in historical perspective, is misleading since it is not exposing the hardship of those in the worst living conditions. [19]

He advocates looking at larger trends in poverty, education, health and violence since these are slowly, but persistently changing the world and are neglected in the reporting of today's mass media. [18]

He is known for his research how global living conditions are changing and his visualisations of these trends. [20] [21] [22] He has shown that in many societies in the past a large share (over 40%) of children died. [23]

He said that there are three messages of his work: "The world is much better; The world is awful; The world can be much better". [16]

Research

Roser's research is concerned with global problems such as poverty, climate change, child mortality and inequality. [2]

In 2015 research with Tony Atkinson, Brian Nolan and others he studied how the benefits from economic growth are distributed. [24] [25] [26]

In October 2019 he co-authored a study of child mortality. It was the first global study that mapped child death on the level of subnational district. [27] The study, published in Nature, was described as an important step to make action possible that further reduces child mortality. [28]

He and Felix Pretis found that the growth rate in CO2 emission intensity exceeded the projections of all climate scenarios. [29] With Jesus Crespo Cuaresma he studied the history of international trade and its impact on economic inequality. [30]

Roser has criticized the practice of focusing on the international poverty line alone. In his research he suggests a poverty at 10.89 international-$ per day. [31] The researchers say this is the minimum level people needed to have access to basic healthcare. The reason for the low global poverty line is to focus the attention on the world's very poorest population. [32] He proposes using several different poverty lines to understand what is happening to global poverty.

In global health research he studied the impact of poverty on poor health and disease and contributed to a textbook on global health. [33] [34]

His most cited article, coauthored with Hannah Ritchie and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, is concerned with global population growth. [35]

Roser is a regular speaker at conferences where he presents empirical data on how the world is changing. [36] He is part of the Statistical Advisory Panel of UNDP. [37] UN Secretary-General António Guterres invited him to internal retreats attended by the heads of the UN institutions to speak about his global development research. [38]

Tina Rosenberg emphasised in The New York Times that Roser's work presents a "big picture that’s an important counterpoint to the constant barrage of negative world news." [39] Angus Deaton cites Roser in his book The Great Escape. [40] His research is cited in academic journals including Science, [41] Nature, [42] and The Lancet. [43] [44]