Major-General Thomas Harrison, baptised 16 July 1616, executed 13 October 1660, was a prominent member of the radical religious sect known as the Fifth Monarchists, and a soldier who fought for Parliament and the Commonwealth in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. One of those who approved the Execution of Charles I in January 1649, he was a strong supporter of Oliver Cromwell before the two fell out when The Protectorate was established in 1653. Following the 1660 Stuart Restoration, he was arrested, found guilty of treason as a regicide, and sentenced to death. He was hanged, drawn and quartered on 13 October 1660, facing his execution with a courage noted by various observers, including the diarist Samuel Pepys.

"An eye for an eye" is a commandment found in the Book of Exodus 21:23–27 expressing the principle of reciprocal justice measure for measure. The earliest known use of the principle appears in the Code of Hammurabi, which predates the Hebrew Bible.

Psalm 51, one of the penitential psalms, is the 51st psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "Have mercy upon me, O God". In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, this psalm is Psalm 50. In Latin, it is known as Miserere, in Ancient Greek: Ἥ Ἐλεήμων, romanized: Hḗ Eleḗmōn), especially in musical settings. The introduction in the text says that it was composed by David as a confession to God after he sinned with Bathsheba.

Psalm 89 is the 89th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "I will sing of the mercies of the LORD for ever". In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, this psalm is Psalm 88. In Latin, it is known as "Misericordias Domini in aeternum cantabo". It is described as a maschil or "contemplation".

Matthew 5:26 is the twenty-sixth verse of the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament and is part of the Sermon on the Mount. Jesus has just warned that if you do not reconcile with your enemies a judge is likely to throw you in jail. In this verse Jesus mentions that your debts must be paid completely before one can leave.

The Ten Commandments, or the Decalogue, are a set of biblical principles relating to ethics and worship originally from the Jewish tradition that play a fundamental role in Judaism and Christianity. The text of the Ten Commandments appears in three different versions in the Bible: at Exodus 20:2–17, Deuteronomy 5:6–21, and the "Ritual Decalogue" of Exodus 34:11–26.

A grace is a short prayer or thankful phrase said before or after eating. The term most commonly refers to Christian traditions. Some traditions hold that grace and thanksgiving imparts a blessing which sanctifies the meal. In English, reciting such a prayer is sometimes referred to as "saying grace". The term comes from the Ecclesiastical Latin phrase gratiarum actio, "act of thanks." Theologically, the act of saying grace is derived from the Bible, in which Jesus and Saint Paul pray before meals. The practice reflects the belief that humans should thank God who is believed to be the origin of everything.

The Prayer of Humble Access is the name traditionally given to a prayer originally from early Anglican Books of Common Prayer and contained in many Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and other Christian eucharistic liturgies, including use by the personal ordinariates for former Anglican groups reconciled to the Catholic Church. Its origins lie in the healing the centurion's servant as recounted in two of the Gospels. It is comparable to the "Domine, non sum dignus" used in the Catholic Mass.

Absolution of the dead is a prayer for or a declaration of absolution of a dead person's sins that takes place at the person's religious funeral.

Judaism offers a variety of views regarding the love of God, love among human beings, and love for non-human animals. Love is a central value in Jewish ethics and Jewish theology.

"I am the LORD thy God" is the opening phrase of the Ten Commandments, which are widely understood as moral imperatives by ancient legal historians and Jewish and Christian biblical scholars.

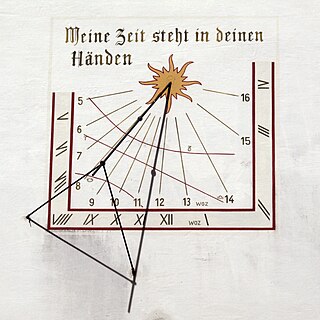

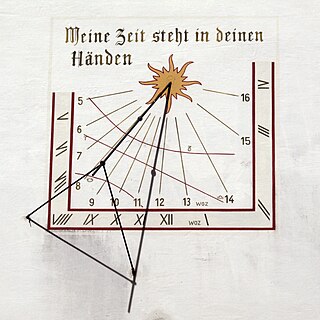

Psalm 31 is the 31st psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "In thee, O LORD, do I put my trust". In Latin, it is known as "In te Domine speravi". The Book of Psalms is part of the third section of the Hebrew Bible, and a book of the Christian Old Testament. In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint version of the Bible, and in its Latin translation, the Vulgate, this psalm is Psalm 30. The first verse in the Hebrew text indicates that it was composed by David.

Psalm 36 is the 36th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The transgression of the wicked saith within my heart". The Book of Psalms is part of the third section of the Hebrew Bible, and a book of the Christian Old Testament. In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, this psalm is Psalm 35. In Latin, it is known as Dixit iniustus or Dixit injustus. The psalm is a hymn psalm, attributed to David.

Psalm 37 is the 37th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "Fret not thyself because of evildoers, neither be thou envious against the workers of iniquity". The Book of Psalms is part of the third section of the Hebrew Bible, and a book of the Christian Old Testament. In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, this psalm is Psalm 36. In Latin, it is known as Noli aemulari in malignantibus. The psalm has the form of an acrostic Hebrew poem, and is thought to have been written by David in his old age.

Psalm 50, a Psalm of Asaph, is the 50th psalm from the Book of Psalms in the Bible, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The mighty God, even the LORD, hath spoken, and called the earth from the rising of the sun unto the going down thereof." In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, this psalm is Psalm 49. The opening words in Latin are Deus deorum, Dominus, locutus est / et vocavit terram a solis ortu usque ad occasum. The psalm is a prophetic imagining of God's judgment on the Israelites.

Psalm 59 is the 59th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "Be merciful unto me, O God, be merciful unto me". In the slightly different numbering system of the Greek Septuagint version of the Bible and the Latin Vulgate, this psalm is Psalm 56. In Latin, it is known as "Eripe me de inimicis meis Deu". It is described as "a prayer composed when Saul sent messengers to wait at the house in order to kill him", and commentator Cyril Rodd describes it as a "vigorous plea for the destruction of the psalmist's enemies".

Brotherly love in the biblical sense is an extension of the natural affection associated with near kin, toward the greater community of fellow believers, that goes beyond the mere duty in Leviticus 19:18 to "love thy neighbour as thyself", and shows itself as "unfeigned love" from a "pure heart", that extends an unconditional hand of friendship that loves when not loved back, that gives without getting, and ever looks for what is best in others.

The Te Deum in D major, "Queen Caroline" is a canticle Te Deum in D major composed by George Frideric Handel in 1714.

"Lest we forget" is a phrase commonly used in war remembrance services and commemorative occasions in English speaking countries, usually those connected to the British Empire, like Canada. Before the term was used in reference to soldiers and war, it was first used in an 1897 Christian poem written by Rudyard Kipling called "Recessional", a poem written to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The phrase occurs eight times; and is repeated at the end of the first four stanzas in order to add particular emphasis regarding the dangers of failing to remember.