The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight uniformed services of the United States as well as to military and political figures of foreign governments.

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the president to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, which took the form of a heart made of purple cloth, the Purple Heart is the oldest military award still given to U.S. military members. The National Purple Heart Hall of Honor is located in New Windsor, New York.

The Commendation Medal is a mid-level United States military decoration presented for sustained acts of heroism or meritorious service. Each branch of the United States Armed Forces issues its own version of the Commendation Medal, with a fifth version existing for acts of joint military service performed under the Department of Defense.

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is the United States Army's second highest military decoration for soldiers who display extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. Actions that merit the Distinguished Service Cross must be of such a high degree that they are above those required for all other U.S. combat decorations, but which do not meet the criteria for the Medal of Honor. The Army Distinguished Service Cross is equivalent to the Naval Services' Navy Cross, the Air and Space Forces' Air Force Cross, and the Coast Guard Cross. Prior to the creation of the Air Force Cross in 1960, airmen were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

The awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces include various medals, service ribbons, ribbon devices, and specific badges which recognize military service and personal accomplishments of members of the U.S. Armed Forces. Such awards are a means to outwardly display the highlights of a service member's career.

The Air Medal (AM) is a military decoration of the United States Armed Forces. It was created in 1942 and is awarded for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight.

The National Defense Service Medal (NDSM) is a service award of the United States Armed Forces established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953. It was awarded to every member of the U.S. Armed Forces who served during any one of four specified periods of armed conflict or national emergency from June 27, 1950 through December 31, 2022. Combat or "in theater" service is not a requirement for the award.

An aviator badge is an insignia used in most of the world's militaries to designate those who have received training and qualification in military aviation. Also known as a pilot's badge, or pilot wings, the aviator badge was first conceived to recognize the training that military aviators receive, as well as provide a means to outwardly differentiate between military pilots and the “foot soldiers” of the regular ground forces.

Chief Warrant officer is a senior warrant officer rank, used in many countries.

The Vietnam Service Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces established on 8 July 1965 by order of President Lyndon B. Johnson. The medal is awarded to recognize service during the Vietnam War by all members of the U.S. Armed Forces provided they meet the award requirements.

A "V" device is a metal 1⁄4-inch (6.4 mm) capital letter "V" with serifs which, when worn on certain decorations awarded by the United States Armed Forces, distinguishes a decoration awarded for combat valor or heroism from the same decoration being awarded for a member's actions under circumstances other than combat.

The Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces, which was first created in 1961 by Executive Order of President John Kennedy. The medal is awarded to members of the U.S. Armed Forces who, after July 1, 1958, participated in U.S. military operations, U.S. operations in direct support of the United Nations, or U.S. operations of assistance for friendly foreign nations.

The Combat Action Badge (CAB) is a United States military award given to soldiers of the U.S. Army of any rank and who are not members of an infantry, special forces, or medical MOS, for being "present and actively engaging or being engaged by the enemy, and performing satisfactorily in accordance with prescribed rules of engagement" at any point in time after 18 September 2001.

Authorized foreign decorations of the United States military are those military decorations which have been approved for wear by members of the United States armed forces but whose awarding authority is the government of a country other than the United States.

Awards and decorations of the Vietnam War were military decorations which were bestowed by the major warring parties that participated in the Vietnam War. North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Australia, New Zealand and the United States all issued awards and decorations to their personnel during, or after, the conflict.

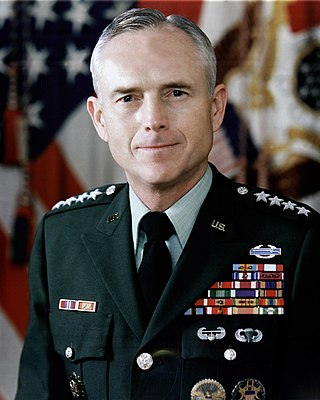

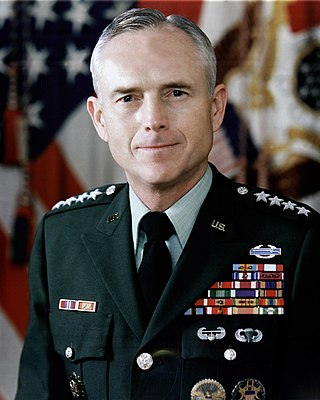

John Adams Wickham Jr. is a retired United States Army general who served as the United States Army Chief of Staff from 1983 to 1987.

William Joseph Gainey is a retired United States Army soldier who served as the first Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

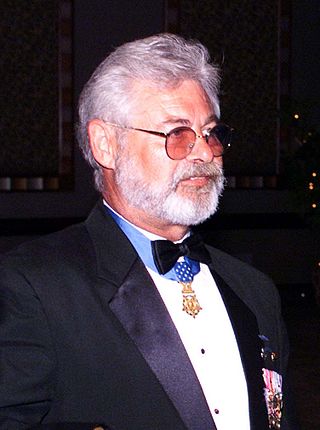

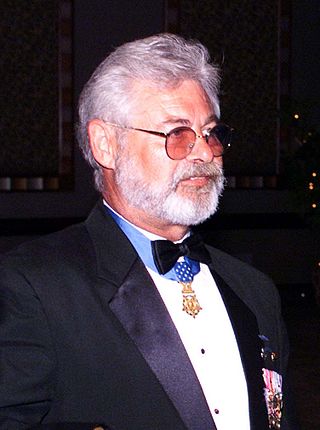

Jonathan Robert Cavaiani was a United States Army soldier and a recipient of the United States military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions in the Vietnam War.

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. The medal is normally awarded by the President of the United States and is presented "in the name of the United States Congress."