Related Research Articles

Sustainable development is the organizing principle for economic development while simultaneously sustaining the ability of natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services on which the economy and society depend. The desired result is a state of society where living conditions and resources are used to continue to meet human needs without undermining the integrity and stability of the natural system. Sustainable development can be defined as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainability goals, such as the current UN-level Sustainable Development Goals, address the global challenges, including poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace and justice.

Natural capital is the world's stock of natural resources, which includes geology, soils, air, water and all living organisms. Some natural capital assets provide people with free goods and services, often called ecosystem services. Two of these underpin our economy and society, and thus make human life possible.

Environmental economics is a sub-field of economics concerned with environmental issues. It has become a widely studied subject due to growing environmental concerns in the twenty-first century. Environmental economics "undertakes theoretical or empirical studies of the economic effects of national or local environmental policies around the world.... Particular issues include the costs and benefits of alternative environmental policies to deal with air pollution, water quality, toxic substances, solid waste, and global warming."

Ecological economics, bioeconomics, ecolonomy, or eco-economics, is both a transdisciplinary and an interdisciplinary field of academic research addressing the interdependence and coevolution of human economies and natural ecosystems, both intertemporally and spatially. By treating the economy as a subsystem of Earth's larger ecosystem, and by emphasizing the preservation of natural capital, the field of ecological economics is differentiated from environmental economics, which is the mainstream economic analysis of the environment. One survey of German economists found that ecological and environmental economics are different schools of economic thought, with ecological economists emphasizing strong sustainability and rejecting the proposition that physical (human-made) capital can substitute for natural capital.

The green economy is defined as economy that aims at making issues of reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities, and that aims for sustainable development without degrading the environment. It is closely related with ecological economics, but has a more politically applied focus. The 2011 UNEP Green Economy Report argues "that to be green, an economy must not only be efficient, but also fair. Fairness implies recognizing global and country level equity dimensions, particularly in assuring a Just Transition to an economy that is low-carbon, resource efficient, and socially inclusive."

Environmental resource management is the management of the interaction and impact of human societies on the environment. It is not, as the phrase might suggest, the management of the environment itself. Environmental resources management aims to ensure that ecosystem services are protected and maintained for future human generations, and also maintain ecosystem integrity through considering ethical, economic, and scientific (ecological) variables. Environmental resource management tries to identify factors affected by conflicts that rise between meeting needs and protecting resources. It is thus linked to environmental protection, sustainability, integrated landscape management, natural resource management, fisheries management, forest management, and wildlife management, and others.

Ecosystem services are the many and varied benefits to humans provided by the natural environment and from healthy ecosystems. Such ecosystems include, for example, agroecosystems, forest ecosystems, grassland ecosystems and aquatic ecosystems. These ecosystems, functioning in healthy relationship, offer such things like natural pollination of crops, clean air, extreme weather mitigation, human mental and physical well-being. Collectively, these benefits are becoming known as 'ecosystem services', and are often integral to the provisioning of clean drinking water, the decomposition of wastes, and resilience and productivity of food ecosystems.

Forest management is a branch of forestry concerned with overall administrative, legal, economic, and social aspects, as well as scientific and technical aspects, such as silviculture, protection, and forest regulation. This includes management for timber, aesthetics, recreation, urban values, water, wildlife, inland and nearshore fisheries, wood products, plant genetic resources, and other forest resource values. Management objectives can be for conservation, utilisation, or a mixture of the two. Techniques include timber extraction, planting and replanting of different species, building and maintenance of roads and pathways through forests, and preventing fire.

Regenerative design is a process-oriented whole systems approach to design. The term "regenerative" describes processes that restore, renew or revitalize their own sources of energy and materials. Regenerative design uses whole systems thinking to create resilient and equitable systems that integrate the needs of society with the integrity of nature.

Ecological design or ecodesign is an approach to designing products with special consideration for the environmental impacts of the product during its whole lifecycle. It was defined by Sim Van der Ryn and Stuart Cowan as "any form of design that minimizes environmentally destructive impacts by integrating itself with living processes." Ecological design is an integrative ecologically responsible design discipline. Ecological design can also be posited as the process within design and development of integration environmental consideration into product design and development with the aim of reducing environmental impacts of products through their life cycle.

Sustainability metrics and indices are measures of sustainability, and attempt to quantify beyond the generic concept. Though there are disagreements among those from different disciplines, these disciplines and international organizations have each offered measures or indicators of how to measure the concept.

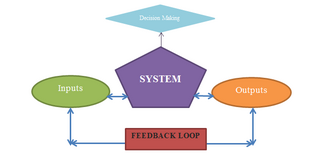

Sustainability is the ability to exist constantly. In the 21st century, it refers generally to the capacity for the biosphere and human civilization to co-exist. It is also defined as the process of people maintaining change in a homeostasis balanced environment, in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development, and institutional change are all in harmony and enhance both current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations. For many in the field, sustainability is defined through the following interconnected domains or pillars: environment, economic and social, which according to Fritjof Capra, is based on the principles of Systems Thinking. Sub-domains of sustainable development have been considered also: cultural, technological and political. According to Our Common Future, sustainable development is defined as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." Sustainable development may be the organizing principle of sustainability, yet others may view the two terms as paradoxical.

Ecosystem management is a process that aims to conserve major ecological services and restore natural resources while meeting the socioeconomic, political, and cultural needs of current and future generations.

The history of sustainability traces human-dominated ecological systems from the earliest civilizations to the present. This history is characterized by the increased regional success of a particular society, followed by crises that were either resolved, producing sustainability, or not, leading to decline.

Environmental governance is a concept in political ecology and environmental policy that advocates sustainability as the supreme consideration for managing all human activities—political, social and economic. Governance includes government, business and civil society, and emphasizes whole system management. To capture this diverse range of elements, environmental governance often employs alternative systems of governance, for example watershed-based management.

Environmentally sustainable design is the philosophy of designing physical objects, the built environment, and services to comply with the principles of ecological sustainability.

The International Resource Panel is a scientific panel of experts that aims to help nations use natural resources sustainably without compromising economic growth and human needs. It provides independent scientific assessments and expert advice on a variety of areas, including:

Forest restoration is defined as “actions to re-instate ecological processes, which accelerate recovery of forest structure, ecological functioning and biodiversity levels towards those typical of climax forest” i.e. the end-stage of natural forest succession. Climax forests are relatively stable ecosystems that have developed the maximum biomass, structural complexity and species diversity that are possible within the limits imposed by climate and soil and without continued disturbance from humans. Climax forest is therefore the target ecosystem, which defines the ultimate aim of forest restoration. Since climate is a major factor that determines climax forest composition, global climate change may result in changing restoration aims.

Resource efficiency is the maximising of the supply of money, materials, staff, and other assets that can be drawn on by a person or organization in order to function effectively, with minimum wasted (natural) resource expenses. It means using the Earth's limited resources in a sustainable manner while minimising environmental impact.

Natural capital accounting is the process of calculating the total stocks and flows of natural resources and services in a given ecosystem or region. Accounting for such goods may occur in physical or monetary terms. This process can subsequently inform government, corporate and consumer decision making as each relates to the use or consumption of natural resources and land, and sustainable behaviour.

References

- ↑ "Melbourne Principles for Sustainable Cities" (PDF). UNEP & ICLEI. 2002-08-21. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ↑ "Operationalising the Melbourne Principles for Sustainable Cities" (PDF). 2005-05-31. Retrieved 6 August 2012.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ "Key Elements of a Proposed 10 Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production" (PDF). UNEP & UNDESA. 2007-12-12. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ "Sustainable Penrith Action Plan" (PDF). Penrith City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.