Pareto efficiency or Pareto optimality is a situation where no action or allocation is available that makes one individual better off without making another worse off. The concept is named after Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), Italian civil engineer and economist, who used the concept in his studies of economic efficiency and income distribution. The following three concepts are closely related:

In economics, utility is a measure of the satisfaction that a certain person has from a certain state of the world. Over time, the term has been used in at least two different meanings.

Behavioral economics is the study of the psychological, cognitive, emotional, cultural and social factors involved in the decisions of individuals or institutions, and how these decisions deviate from those implied by classical economic theory.

In economics and finance, risk aversion is the tendency of people to prefer outcomes with low uncertainty to those outcomes with high uncertainty, even if the average outcome of the latter is equal to or higher in monetary value than the more certain outcome.

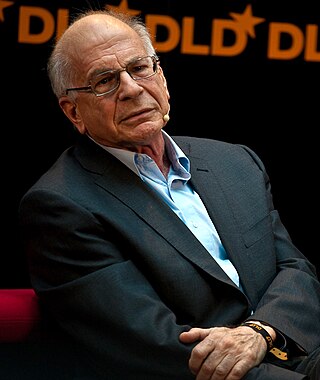

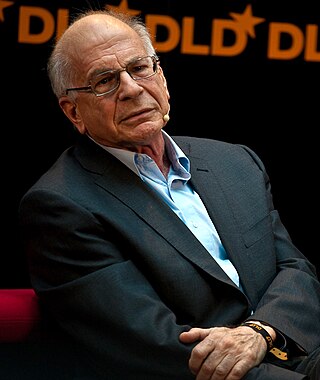

Prospect theory is a theory of behavioral economics, judgment and decision making that was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. The theory was cited in the decision to award Kahneman the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption, by maximizing utility subject to a consumer budget constraint. Factors influencing consumers' evaluation of the utility of goods include: income level, cultural factors, product information and physio-psychological factors.

Loss aversion is a psychological and economic concept, which refers to how outcomes are interpreted as gains and losses where losses are subject to more sensitivity in people's responses compared to equivalent gains acquired. Kahneman and Tversky (1992) suggested that losses can be twice as powerful psychologically as gains.

The expected utility hypothesis is a foundational assumption in mathematical economics concerning decision making under uncertainty. It postulates that rational agents maximize utility, meaning the subjective desirability of their actions. Rational choice theory, a cornerstone of microeconomics, builds this postulate to model aggregate social behaviour.

Status quo bias is an emotional bias; a preference for the maintenance of one's current or previous state of affairs, or a preference to not undertake any action to change this current or previous state. The current baseline is taken as a reference point, and any change from that baseline is perceived as a loss or gain. Corresponding to different alternatives, this current baseline or default option is perceived and evaluated by individuals as a positive.

In psychology and behavioral economics, the endowment effect is the finding that people are more likely to retain an object they own than acquire that same object when they do not own it. The endowment theory can be defined as "an application of prospect theory positing that loss aversion associated with ownership explains observed exchange asymmetries."

In economics, hyperbolic discounting is a time-inconsistent model of delay discounting. It is one of the cornerstones of behavioral economics and its brain-basis is actively being studied by neuroeconomics researchers.

Utility maximization was first developed by utilitarian philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. In microeconomics, the utility maximization problem is the problem consumers face: "How should I spend my money in order to maximize my utility?" It is a type of optimal decision problem. It consists of choosing how much of each available good or service to consume, taking into account a constraint on total spending (income), the prices of the goods and their preferences.

The equity premium puzzle refers to the inability of an important class of economic models to explain the average equity risk premium (ERP) provided by a diversified portfolio of equities over that of government bonds, which has been observed for more than 100 years. There is a significant disparity between returns produced by stocks compared to returns produced by government treasury bills. The equity premium puzzle addresses the difficulty in understanding and explaining this disparity. This disparity is calculated using the equity risk premium:

In social psychology, social value orientation (SVO) is a person's preference about how to allocate resources between the self and another person. SVO corresponds to how much weight a person attaches to the welfare of others in relation to the own. Since people are assumed to vary in the weight they attach to other peoples' outcomes in relation to their own, SVO is an individual difference variable. The general concept underlying SVO has become widely studied in a variety of different scientific disciplines, such as economics, sociology, and biology under a multitude of different names.

Choice architecture is the design of different ways in which choices can be presented to decision makers, and the impact of that presentation on decision-making. For example, each of the following:

In economics, willingness to accept (WTA) is the minimum monetary amount that а person is willing to accept to sell a good or service, or to bear a negative externality, such as pollution. This is in contrast to willingness to pay (WTP), which is the maximum amount of money a consumer is willing to sacrifice to purchase a good/service or avoid something undesirable. The price of any transaction will thus be any point between a buyer's willingness to pay and a seller's willingness to accept; the net difference is the economic surplus.

In decision theory, the von Neumann–Morgenstern (VNM) utility theorem shows that, under certain axioms of rational behavior, a decision-maker faced with risky (probabilistic) outcomes of different choices will behave as if they are maximizing the expected value of some function defined over the potential outcomes at some specified point in the future. This function is known as the von Neumann–Morgenstern utility function. The theorem is the basis for expected utility theory.

In economics, and in other social sciences, preference refers to an order by which an agent, while in search of an "optimal choice", ranks alternatives based on their respective utility. Preferences are evaluations that concern matters of value, in relation to practical reasoning. Individual preferences are determined by taste, need, ..., as opposed to price, availability or personal income. Classical economics assumes that people act in their best (rational) interest. In this context, rationality would dictate that, when given a choice, an individual will select an option that maximizes their self-interest. But preferences are not always transitive, both because real humans are far from always being rational and because in some situations preferences can form cycles, in which case there exists no well-defined optimal choice. An example of this is Efron dice.

In psychology, economics and philosophy, preference is a technical term usually used in relation to choosing between alternatives. For example, someone prefers A over B if they would rather choose A than B. Preferences are central to decision theory because of this relation to behavior. Some methods such as Ordinal Priority Approach use preference relation for decision-making. As connative states, they are closely related to desires. The difference between the two is that desires are directed at one object while preferences concern a comparison between two alternatives, of which one is preferred to the other.

The uncertainty effect, also known as direct risk aversion, is a phenomenon from economics and psychology which suggests that individuals may be prone to expressing such an extreme distaste for risk that they ascribe a lower value to a risky prospect than its worst possible realization.