Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence). A person who commits espionage is called an espionage agent or spy. Any individual or spy ring, in the service of a government, company, criminal organization, or independent operation, can commit espionage. The practice is clandestine, as it is by definition unwelcome. In some circumstances, it may be a legal tool of law enforcement and in others, it may be illegal and punishable by law.

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service and later absorbed by the National Security Agency (NSA), that ran from February 1, 1943, until October 1, 1980. It was intended to decrypt messages transmitted by the intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union. Initiated when the Soviet Union was an ally of the US, the program continued during the Cold War, when the Soviet Union was considered an enemy.

Robert Philip Hanssen was an American Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent who spied for Soviet and Russian intelligence services against the United States from 1979 to 2001. His espionage was described by the Department of Justice as "possibly the worst intelligence disaster in U.S. history".

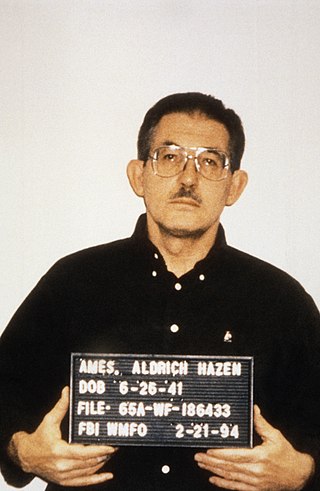

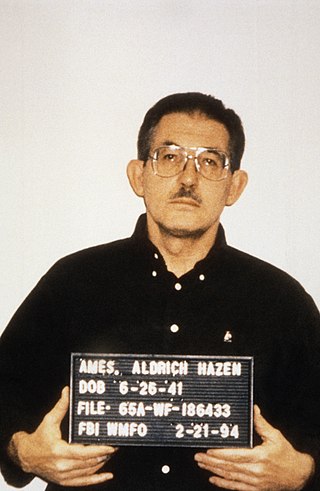

Aldrich Hazen Ames is an American former CIA counterintelligence officer who was convicted of espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union and Russia in 1994. He is serving a life sentence, without the possibility of parole, in the Federal Correctional Institution in Terre Haute, Indiana. Ames was known to have compromised more highly classified CIA assets than any other officer until Robert Hanssen, who was arrested seven years later in 2001.

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or other intelligence activities conducted by, for, or on behalf of foreign powers, organizations or persons.

An intelligence officer is a person employed by an organization to collect, compile or analyze information which is of use to that organization. The word of officer is a working title, not a rank, used in the same way a "police officer" can also be a sergeant, or in the military, in which non-commissioned personnel may serve as intelligence officers.

The Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation or SVR RF is Russia's external intelligence agency, focusing mainly on civilian affairs. The SVR RF succeeded the First Chief Directorate (PGU) of the KGB in December 1991. The SVR has its headquarters in the Yasenevo District of Moscow with its director reporting directly to the President of the Russian Federation.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is a 1974 spy novel by British-Irish author John le Carré. It follows the endeavours of taciturn, aging spymaster George Smiley to uncover a Soviet mole in the British Secret Intelligence Service. The novel has received critical acclaim for its complex social commentary—and, at the time, relevance, following the defection of Kim Philby. It has been adapted into both a television series and a film, and remains a staple of the spy fiction genre.

The Ministry of State Security is the principal civilian intelligence, security and secret police agency of the People's Republic of China, responsible for foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, and the political security of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). One of the largest and most secretive intelligence organizations in the world, it is headquartered in the Haidian District of Beijing, with powerful semi-autonomous branches at the provincial, city, municipality and township levels throughout China.

Anatoliy Mikhaylovich Golitsyn CBE was a Soviet KGB defector and author of two books about the long-term deception strategy of the KGB leadership. He was born in Pyriatyn, USSR. He provided "a wide range of intelligence to the CIA on the operations of most of the 'Lines' (departments) at the Helsinki and other residencies, as well as KGB methods of recruiting and running agents." He became an American citizen by 1984.

As early as the 1920s, the Soviet Union, through its GRU, OGPU, NKVD, and KGB intelligence agencies, used Russian and foreign-born nationals, as well as Communists of American origin, to perform espionage activities in the United States, forming various spy rings. Particularly during the 1940s, some of these espionage networks had contact with various U.S. government agencies. These Soviet espionage networks illegally transmitted confidential information to Moscow, such as information on the development of the atomic bomb. Soviet spies also participated in propaganda and disinformation operations, known as active measures, and attempted to sabotage diplomatic relationships between the U.S. and its allies.

Bill Haydon is a fictional character created by John le Carré who features in le Carré's 1974 novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. He is a senior officer in the British Secret Intelligence Service who serves as a Soviet mole. The novel follows aging spymaster George Smiley's endeavours to uncover the mole. The character is partly modelled after the real-life double agent Kim Philby, part of the notorious Cambridge Five spy ring in Britain, who defected to the USSR in 1963.

Clandestine human intelligence is intelligence collected from human sources using clandestine espionage methods. These sources consist of people working in a variety of roles within the intelligence community. Examples include the quintessential spy, who collects intelligence; couriers and related personnel, who handle an intelligence organization's (ideally) secure communications; and support personnel, such as access agents, who may arrange the contact between the potential spy and the case officer who recruits them. The recruiter and supervising agent may not necessarily be the same individual. Large espionage networks may be composed of multiple levels of spies, support personnel, and supervisors. Espionage networks are typically organized as a cell system, in which each clandestine operator knows only the people in his own cell, perhaps the external case officer, and an emergency method to contact higher levels if the case officer or cell leader is captured, but has no knowledge of people in other cells. This cellular organization is a form of compartmentalisation, which is an important tactic for controlling access to information, used in order to diminish the risk of discovery of the network or the release of sensitive information.

The Clandestine HUMINT page adheres to the functions within the discipline, including espionage and active counterintelligence.

Clandestine HUMINT asset recruiting refers to the recruitment of human agents, commonly known as spies, who work for a foreign government, or within a host country's government or other target of intelligence interest for the gathering of human intelligence. The work of detecting and "doubling" spies who betray their oaths to work on behalf of a foreign intelligence agency is an important part of counterintelligence.

Pyotr Semyonovich Popov was a colonel in the Soviet military intelligence apparatus (GRU). He was the first GRU officer to offer his services to the Central Intelligence Agency after World War II. Between 1953 and 1958, he provided the United States government with large amounts of information concerning military capabilities and espionage operations. He was codenamed ATTIC for most of his time with the CIA, and his case officer was George Kisevalter.

The Committee for State Security was the main security agency for the Soviet Union from 13 March 1954 until 3 December 1991. As a direct successor of preceding agencies such as the Cheka, GPU, OGPU, NKGB, NKVD and MGB, it was attached to the Council of Ministers. It was the chief government agency of "union-republican jurisdiction", carrying out internal security, foreign intelligence, counter-intelligence and secret police functions. Similar agencies operated in each of the republics of the Soviet Union aside from the Russian SFSR, where the KGB was headquartered, with many associated ministries, state committees and state commissions.

Russian espionage in the United States has occurred since at least the Cold War, and likely well before. According to the United States government, by 2007 it had reached Cold War levels.

David Henry Blee served in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from its founding in 1947 until his 1985 retirement. During World War II in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), he had worked in Southeast Asia. In the CIA, he served as Chief of Station (COS) in Asia and Africa, starting in the 1950s. He then led the CIA's Near East Division.