Related Research Articles

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polygenic) or by a chromosomal abnormality. Although polygenic disorders are the most common, the term is mostly used when discussing disorders with a single genetic cause, either in a gene or chromosome. The mutation responsible can occur spontaneously before embryonic development, or it can be inherited from two parents who are carriers of a faulty gene or from a parent with the disorder. When the genetic disorder is inherited from one or both parents, it is also classified as a hereditary disease. Some disorders are caused by a mutation on the X chromosome and have X-linked inheritance. Very few disorders are inherited on the Y chromosome or mitochondrial DNA.

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a specific gene depends on the number of copies of each chromosome found in that species, also referred to as ploidy. In diploid species like humans, two full sets of chromosomes are present, meaning each individual has two alleles for any given gene. If both alleles are the same, the genotype is referred to as homozygous. If the alleles are different, the genotype is referred to as heterozygous.

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic information of their parents. Through heredity, variations between individuals can accumulate and cause species to evolve by natural selection. The study of heredity in biology is genetics.

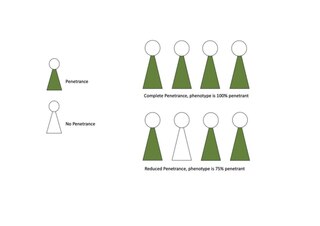

Penetrance in genetics is the proportion of individuals carrying a particular variant of a gene (genotype) that also expresses an associated trait (phenotype). In medical genetics, the penetrance of a disease-causing mutation is the proportion of individuals with the mutation that exhibit clinical symptoms among all individuals with such mutation. For example: If a mutation in the gene responsible for a particular autosomal dominant disorder has 75% penetrance, then 75% of those with the mutation will go on to develop the disease, showing its phenotype, whereas 25% will not.

A quantitative trait locus (QTL) is a locus that correlates with variation of a quantitative trait in the phenotype of a population of organisms. QTLs are mapped by identifying which molecular markers correlate with an observed trait. This is often an early step in identifying the actual genes that cause the trait variation.

Human behaviour genetics is an interdisciplinary subfield of behaviour genetics that studies the role of genetic and environmental influences on human behaviour. Classically, human behavioural geneticists have studied the inheritance of behavioural traits. The field was originally focused on determining the importance of genetic influences on human behaviour. It has evolved to address more complex questions such as: how important are genetic and/or environmental influences on various human behavioural traits; to what extent do the same genetic and/or environmental influences impact the overlap between human behavioural traits; how do genetic and/or environmental influences on behaviour change across development; and what environmental factors moderate the importance of genetic effects on human behaviour. The field is interdisciplinary, and draws from genetics, psychology, and statistics. Most recently, the field has moved into the area of statistical genetics, with many behavioural geneticists also involved in efforts to identify the specific genes involved in human behaviour, and to understand how the effects associated with these genes changes across time, and in conjunction with the environment.

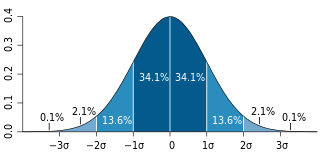

Genetic architecture is the underlying genetic basis of a phenotypic trait and its variational properties. Phenotypic variation for quantitative traits is, at the most basic level, the result of the segregation of alleles at quantitative trait loci (QTL). Environmental factors and other external influences can also play a role in phenotypic variation. Genetic architecture is a broad term that can be described for any given individual based on information regarding gene and allele number, the distribution of allelic and mutational effects, and patterns of pleiotropy, dominance, and epistasis.

Human genetics is the study of inheritance as it occurs in human beings. Human genetics encompasses a variety of overlapping fields including: classical genetics, cytogenetics, molecular genetics, biochemical genetics, genomics, population genetics, developmental genetics, clinical genetics, and genetic counseling.

In genetics, expressivity is the degree to which a phenotype is expressed by individuals having a particular genotype. Alternatively, it may refer to the expression of a particular gene by individuals having a certain phenotype. Expressivity is related to the intensity of a given phenotype; it differs from penetrance, which refers to the proportion of individuals with a particular genotype that share the same phenotype.

A polygene is a member of a group of non-epistatic genes that interact additively to influence a phenotypic trait, thus contributing to multiple-gene inheritance, a type of non-Mendelian inheritance, as opposed to single-gene inheritance, which is the core notion of Mendelian inheritance. The term "monozygous" is usually used to refer to a hypothetical gene as it is often difficult to distinguish the effect of an individual gene from the effects of other genes and the environment on a particular phenotype. Advances in statistical methodology and high throughput sequencing are, however, allowing researchers to locate candidate genes for the trait. In the case that such a gene is identified, it is referred to as a quantitative trait locus (QTL). These genes are generally pleiotropic as well. The genes that contribute to type 2 diabetes are thought to be mostly polygenes. In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all organisms living on Earth.

Gene–environment interaction is when two different genotypes respond to environmental variation in different ways. A norm of reaction is a graph that shows the relationship between genes and environmental factors when phenotypic differences are continuous. They can help illustrate GxE interactions. When the norm of reaction is not parallel, as shown in the figure below, there is a gene by environment interaction. This indicates that each genotype responds to environmental variation in a different way. Environmental variation can be physical, chemical, biological, behavior patterns or life events.

Genetic association is when one or more genotypes within a population co-occur with a phenotypic trait more often than would be expected by chance occurrence.

In mathematical or statistical modeling a threshold model is any model where a threshold value, or set of threshold values, is used to distinguish ranges of values where the behaviour predicted by the model varies in some important way. A particularly important instance arises in toxicology, where the model for the effect of a drug may be that there is zero effect for a dose below a critical or threshold value, while an effect of some significance exists above that value. Certain types of regression model may include threshold effects.

Genetic epidemiology is the study of the role of genetic factors in determining health and disease in families and in populations, and the interplay of such genetic factors with environmental factors. Genetic epidemiology seeks to derive a statistical and quantitative analysis of how genetics work in large groups.

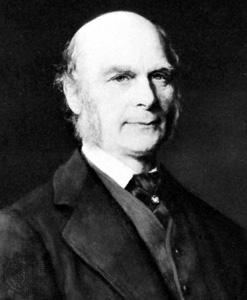

Behavioural genetics, also referred to as behaviour genetics, is a field of scientific research that uses genetic methods to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behaviour. While the name "behavioural genetics" connotes a focus on genetic influences, the field broadly investigates the extent to which genetic and environmental factors influence individual differences, and the development of research designs that can remove the confounding of genes and environment. Behavioural genetics was founded as a scientific discipline by Francis Galton in the late 19th century, only to be discredited through association with eugenics movements before and during World War II. In the latter half of the 20th century, the field saw renewed prominence with research on inheritance of behaviour and mental illness in humans, as well as research on genetically informative model organisms through selective breeding and crosses. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, technological advances in molecular genetics made it possible to measure and modify the genome directly. This led to major advances in model organism research and in human studies, leading to new scientific discoveries.

Addiction vulnerability is an individual's risk of developing an addiction during their lifetime. There are a range of genetic and environmental risk factors for developing an addiction that vary across the population. Genetic and environmental risk factors each account for roughly half of an individual's risk for developing an addiction; the contribution from epigenetic risk factors to the total risk is unknown. Even in individuals with a relatively low genetic risk, exposure to sufficiently high doses of an addictive drug for a long period of time can result in an addiction. In other words, anyone can become an individual with a substance use disorder under particular circumstances. Research is working toward establishing a comprehensive picture of the neurobiology of addiction vulnerability, including all factors at work in propensity for addiction.

Oligogenic inheritance describes a trait that is influenced by a few genes. Oligogenic inheritance represents an intermediate between monogenic inheritance in which a trait is determined by a single causative gene, and polygenic inheritance, in which a trait is influenced by many genes and often environmental factors.

Mendelian traits behave according to the model of monogenic or simple gene inheritance in which one gene corresponds to one trait. Discrete traits with simple Mendelian inheritance patterns are relatively rare in nature, and many of the clearest examples in humans cause disorders. Discrete traits found in humans are common examples for teaching genetics.

A human disease modifier gene is a modifier gene that alters expression of a human gene at another locus that in turn causes a genetic disease. Whereas medical genetics has tended to distinguish between monogenic traits, governed by simple, Mendelian inheritance, and quantitative traits, with cumulative, multifactorial causes, increasing evidence suggests that human diseases exist on a continuous spectrum between the two.

Complex traits, also known as quantitative traits, are traits that do not behave according to simple Mendelian inheritance laws. More specifically, their inheritance cannot be explained by the genetic segregation of a single gene. Such traits show a continuous range of variation and are influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. Compared to strictly Mendelian traits, complex traits are far more common, and because they can be hugely polygenic, they are studied using statistical techniques such as quantitative genetics and quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping rather than classical genetics methods. Examples of complex traits include height, circadian rhythms, enzyme kinetics, and many diseases including diabetes and Parkinson's disease. One major goal of genetic research today is to better understand the molecular mechanisms through which genetic variants act to influence complex traits.

References

- ↑ Duarte, Christine W.; Vaughan, Laura K.; Beasley, T. Mark; Tiwari, Hemant K. (2013), "Multifactorial Inheritance and Complex Diseases", Emery and Rimoin's Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics, Elsevier, pp. 1–15, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-383834-6.00014-8, ISBN 978-0-12-383834-6, S2CID 160734530

- ↑ Plomin, Robert; Haworth, Claire M. A.; Davis, Oliver S. P. (2009-10-27). "Common disorders are quantitative traits". Nature Reviews Genetics. 10 (12): 872–878. doi:10.1038/nrg2670. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 19859063. S2CID 13789104.

- ↑ "11. Multifactorial Inheritance". www2.med.wayne.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- 1 2 The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. (2014, August 24). Multifactorial inheritance and birth defects. Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/multifactorial-inheritance-and-birth-defects

- ↑ Korf, Bruce R.; Sathienkijkanchai, Achara (2009), "Introduction to Human Genetics", Clinical and Translational Science, Elsevier, pp. 265–287, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-373639-0.00019-4, ISBN 978-0-12-373639-0

- ↑ Sayed-Tabatabaei, F.A.; Oostra, B.A.; Isaacs, A.; van Duijn, C.M.; Witteman, J.C.M. (2006-05-12). "ACE Polymorphisms". Circulation Research. 98 (9): 1123–1133. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000223145.74217.e7 . ISSN 0009-7330. PMID 16690893.

- ↑ Neil, Jason R; Galliher, Amy J; Schiemann, William P (April 2006). "TGF-β in cancer and other diseases". Future Oncology. 2 (2): 185–189. doi:10.2217/14796694.2.2.185. ISSN 1479-6694. PMID 16563087.

- ↑ Russo, Cristina; Polosa, Riccardo (2005-07-25). "TNF-α as a promising therapeutic target in chronic asthma: a lesson from rheumatoid arthritis". Clinical Science. 109 (2): 135–142. doi:10.1042/cs20050038. ISSN 0143-5221. PMID 16033328.

- 1 2 Bartee, L., Shriner, W., & Creech, C. (n.d.). Multifactorial disorders and genetic predispositions. Principles of Biology.https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/mhccmajorsbio/chapter/complex-multifactorial-disorders/

- ↑ Pereira, Mark A; Kartashov, Alex I; Ebbeling, Cara B; Van Horn, Linda; Slattery, Martha L; Jacobs, David R; Ludwig, David S (January 2005). "Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis". The Lancet. 365 (9453): 36–42. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17663-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 15639678. S2CID 205941559.

- ↑ Scherer, Stephen (2005-08-01). "Faculty of 1000 evaluation for Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins". doi: 10.3410/f.1026838.326638 .

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Carpenter, Geoffrey (December 1982). "Copeland, John G. et al. Telemundo: A Basic Reader. New York: Random House, Inc., 1980; Freeman, G. Ronald. Intercambios: An Activities Manual. New York: Random House, Inc., 1980Copeland, John G. et al. Telemundo: A Basic Reader. New York: Random House, Inc., 1980. Pp. 264.Freeman, G. Ronald. Intercambios: An Activities Manual. New York: Random House, Inc., 1980. Pp. 209". Canadian Modern Language Review. 38 (2): 361a–362. doi:10.3138/cmlr.38.2.361a. ISSN 0008-4506.

- ↑ "The average contribution of each several ancestor to the total heritage of the offspring". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 61 (369–377): 401–413. 1897-12-31. doi: 10.1098/rspl.1897.0052 . ISSN 0370-1662.

- ↑ "The average contribution of each several ancestor to the total heritage of the offspring". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 61 (369–377): 401–413. 1897-12-31. doi: 10.1098/rspl.1897.0052 . ISSN 0370-1662.

- ↑ Mossey, P. A. (June 1999). "The Heritability of Malocclusion: Part 1—Genetics, Principles and Terminology". British Journal of Orthodontics. 26 (2): 103–113. doi:10.1093/ortho/26.2.103. ISSN 0301-228X. PMID 10420244.

- ↑ Olby, Robert C. (October 2000). "Horticulture: the font for the baptism of genetics". Nature Reviews Genetics. 1 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1038/35049583. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 11262877. S2CID 1896451.