Related Research Articles

A headache is often present in patients with epilepsy. If the headache occurs in the vicinity of a seizure, it is defined as peri-ictal headache, which can occur either before (pre-ictal) or after (post-ictal) the seizure, to which the term ictal refers. An ictal headache itself may or may not be an epileptic manifestation. In the first case it is defined as ictal epileptic headache or simply epileptic headache. It is a real painful seizure, that can remain isolated or be followed by other manifestations of the seizure. On the other hand, the ictal non-epileptic headache is a headache that occurs during a seizure but it is not due to an epileptic mechanism. When the headache does not occur in the vicinity of a seizure it is defined as inter-ictal headache. In this case it is a disorder autonomous from epilepsy, that is a comorbidity.

Ruben Kuzniecky, M.D. is Vice-chair academic affairs and professor of neurology at Northwell Health specializing in the field of epilepsy, epilepsy surgery and neuro-imaging.

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is a chronic disorder of the nervous system which is characterized by recurrent, unprovoked focal seizures that originate in the temporal lobe of the brain and last about one or two minutes. TLE is the most common form of epilepsy with focal seizures. A focal seizure in the temporal lobe may spread to other areas in the brain when it may become a focal to bilateral seizure.

Reflex seizures are epileptic seizures that are consistently induced by a specific stimulus or trigger making them distinct from other epileptic seizures, which are usually unprovoked. Reflex seizures are otherwise similar to unprovoked seizures and may be focal, generalized, myoclonic, or absence seizures. Epilepsy syndromes characterized by repeated reflex seizures are known as reflex epilepsies. Photosensitive seizures are often myoclonic, absence, or focal seizures in the occipital lobe, while musicogenic seizures are associated with focal seizures in the temporal lobe.

Frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) is a neurological disorder that is characterized by brief, recurring seizures arising in the frontal lobes of the brain, that often occur during sleep. It is the second most common type of epilepsy after temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), and is related to the temporal form in that both forms are characterized by partial (focal) seizures.

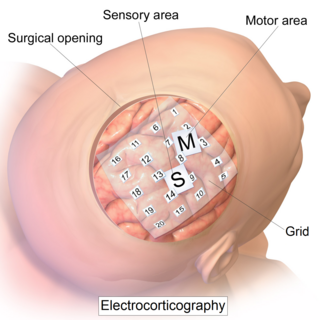

Electrocorticography (ECoG), or intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG), is a type of electrophysiological monitoring that uses electrodes placed directly on the exposed surface of the brain to record electrical activity from the cerebral cortex. In contrast, conventional electroencephalography (EEG) electrodes monitor this activity from outside the skull. ECoG may be performed either in the operating room during surgery or outside of surgery. Because a craniotomy is required to implant the electrode grid, ECoG is an invasive procedure.

Seizure types most commonly follow the classification proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) in 1981. These classifications have been updated in 2017. Distinguishing between seizure types is important since different types of seizure may have different causes, outcomes and treatments.

Abdominal epilepsy is a rare condition most frequently found in children, consisting of gastrointestinal disturbances caused by epileptiform seizure activity. Though a few cases of it have been reported in adults too. It has been described as a type of temporal lobe epilepsy. Responsiveness to anticonvulsants can aid in the diagnosis. Distinguishing features of abdominal epilepsy include (1) Abnormal laboratory, radiographic, and endoscopic findings revealing paroxysmal GI manifestations of unknown origin (2) CNS symptoms (3) Abnormal EEG. Most published medical literature dealing with abdominal epilepsy is in the form of individual case reports. A 2005 review article found a total of 36 cases described in the medical literature.

Epilepsy surgery involves a neurosurgical procedure where an area of the brain involved in seizures is either resected, ablated, disconnected or stimulated. The goal is to eliminate seizures or significantly reduce seizure burden. Approximately 60% of all people with epilepsy have focal epilepsy syndromes. In 15% to 20% of these patients, the condition is not adequately controlled with anticonvulsive drugs. Such patients are potential candidates for surgical epilepsy treatment.

ISAS is an objective tool for analyzing ictal vs. interictal SPECT scans. The goal of ictal SPECT is to localize the region of seizure onset for epilepsy surgery planning. ISAS was introduced and validated in two recent studies. This site is a technical supplement to, which should enable ISAS to be implemented at any center for further study and analysis.

Geschwind syndrome, also known as Gastaut-Geschwind, is a group of behavioral phenomena evident in some people with temporal lobe epilepsy. It is named for one of the first individuals to categorize the symptoms, Norman Geschwind, who published prolifically on the topic from 1973 to 1984. There is controversy surrounding whether it is a true neuropsychiatric disorder. Temporal lobe epilepsy causes chronic, mild, interictal changes in personality, which slowly intensify over time. Geschwind syndrome includes five primary changes; hypergraphia, hyperreligiosity, atypical sexuality, circumstantiality, and intensified mental life. Not all symptoms must be present for a diagnosis. Only some people with epilepsy or temporal lobe epilepsy show features of Geschwind syndrome.

Benign Rolandic epilepsy or self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes is the most common epilepsy syndrome in childhood. Most children will outgrow the syndrome, hence the label benign. The seizures, sometimes referred to as sylvian seizures, start around the central sulcus of the brain.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome is a common idiopathic childhood-related seizure disorder that occurs exclusively in otherwise normal children and manifests mainly with autonomic epileptic seizures and autonomic status epilepticus. An expert consensus has defined Panayiotopoulos syndrome as "a benign age-related focal seizure disorder occurring in early and mid-childhood. It is characterized by seizures, often prolonged, with predominantly autonomic symptoms, and by an EEG [electroencephalogram] that shows shifting and/or multiple foci, often with occipital predominance."

Vertiginous epilepsy is infrequently the first symptom of a seizure, characterized by a feeling of vertigo. When it occurs, there is a sensation of rotation or movement that lasts for a few seconds before full seizure activity. While the specific causes of this disease are speculative there are several methods for diagnosis, the most important being the patient's recall of episodes. Most times, those diagnosed with vertiginous seizures are left to self-manage their symptoms or are able to use anti-epileptic medication to dampen the severity of their symptoms.

People with epilepsy may be classified into different syndromes based on specific clinical features. These features include the age at which seizures begin, the seizure types, and EEG findings, among others. Identifying an epilepsy syndrome is useful as it helps determine the underlying causes as well as deciding what anti-seizure medication should be tried. Epilepsy syndromes are more commonly diagnosed in infants and children. Some examples of epilepsy syndromes include benign rolandic epilepsy, childhood absence epilepsy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Severe syndromes with diffuse brain dysfunction caused, at least partly, by some aspect of epilepsy, are also referred to as epileptic encephalopathies. These are associated with frequent seizures that are resistant to treatment and severe cognitive dysfunction, for instance Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and West syndrome.

Drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE), also known as refractory epilepsy or pharmacoresistant epilepsy, is diagnosed when there failure of adequate trials of two tolerated and appropriately chosen and used antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) to achieve sustained seizure freedom. The probability that the next medication will achieve seizure freedom drops with every failed AED. For example, after two failed AEDs, the probability that the third will achieve seizure freedom is around 4%. Drug-resistant epilepsy is commonly diagnosed after several years of uncontrolled seizures, however, in most cases, it is evident much earlier. Approximately 30% of people with epilepsy have a drug-resistant form.

Occipital epilepsy is a neurological disorder that arises from excessive neural activity in the occipital lobe of the brain that may or may not be symptomatic. Occipital lobe epilepsy is fairly rare, and may sometimes be misdiagnosed as migraine when symptomatic. Epileptic seizures are the result of synchronized neural activity that is excessive, and may stem from a failure of inhibitory neurons to regulate properly.

Fabrice Bartolomei is a French neurophysiologist, and University Professor at Aix-Marseille University (AMU), leading the Service de Neurophysiologie Clinique of the Timone Hospital at the Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Marseille, and he is the medical director of the ‘Centre Saint-Paul - Hopital Henri Gastaut’. He is the coordinator of the clinical network CINAPSE that is dedicated to the management of adult and pediatric cases of severe epilepsies and leader of the Federation Hospitalo-Universitaire Epinext. He is also member of the research unit Institut de Neurosciences des Systèmes](INS), UMR1106, Inserm - AMU.

Musicogenic seizure, also known as music-induced seizure, is a rare type of seizure, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10,000,000 individuals, that arises from disorganized or abnormal brain electrical activity when a person hears or is exposed to a specific type of sound or musical stimuli. There are challenges when diagnosing a music-induced seizure due to the broad scope of triggers, and time delay between a stimulus and seizure. In addition, the causes of musicogenic seizures are not well-established as solely limited cases and research have been discovered and conducted respectively. Nevertheless, the current understanding of the mechanism behind musicogenic seizure is that music triggers the part of the brain that is responsible for evoking an emotion associated with that music. Dysfunction in this system leads to an abnormal release of dopamine, eventually inducing seizure.

Malignant migrating partial seizures of infancy (MMPSI) is a rare epileptic syndrome that onsets before 6 months of age, commonly in the first few weeks of life. Once seizures start, the site of seizure activity repeatedly migrates from one area of the brain to another, with few periods of remission in between. These seizures are 'focal' (updated term for 'partial'), meaning they do not affect both sides of the brain at the same time. These continuous seizures cause damage to the brain, hence the descriptor 'malignant.'

References

- ↑ Stern, John (2015). "Musicogenic epilepsy". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 129: 469–477. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00026-3. ISBN 9780444626301. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 25726285.

- ↑ "music and epilepsy". Epilepsy Society. 2015-08-10. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ↑ Scaliger JJ. Le Loirier’s Treatise of Spectres (1605; cited after Critchley 1937)

- ↑ Schaarschmidt A, Hrsg. D(r.) Samuel Schaarschmidts Medicinischer und Chirurgischer Nachrichten sechster Theil, mit einem Register nebst einer Vorrede versehen. Berlin, J. J. Schütz 1748: 93–97

- ↑ Cooke J. History and Method of Cure of the Various Species of Epilepsy: Being the Second Part of the Second Vol of: A Treatise on Nervous Diseases. London, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown 1823; Reprint: Birmingham, Alabama, The Classics of Medicine Library, Gryphon Editions 1984: 63

- ↑ Gowers WR. Epilepsy and Other Chronic Convulsive Diseases: Their Causes, Symptoms & Treatment. London, J. & A. Churchill 1881

- ↑ Bechterev VM. O reflektornoi epilepsi pod oliyaniemevyookovich razdrazheniye [Artikel in Russisch] Obozrenie Psichiat Nevrol 1914; 15: 513–520

- ↑ Critchley M. Musicogenic epilepsy. Brain 1937; 60: 13–27

- ↑ "Musicogenic epilepsy and epileptic music: a seizure's song (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ↑ Kaplan PW. Musicogenic epilepsy and epileptic music: a seizure’s song. Epilepsy Behav 2003; 4: 464–473

- ↑ Sutherling WW, Hershman LM, Miller JQ, Lee SI. Seizures induced by playing music. Neurology 1980; 30: 1001–1004

- ↑ Rose, Frank Clifford (2010). Neurology of Music. World Scientific. ISBN 9781848162686.

- ↑ Wieser HG, Hungerbühler H, Siegel AM, et al. Musicogenic epilepsy: review of the literature and case report with ictal single photon emission computed tomography. Epilepsia 1997; 38: 200–207

- ↑ Gelisse P, Thomas P, Padovani R, et al. Ictal SPECT in a case of pure musicogenic epilepsy. Epileptic Disord 2003; 5: 133–137

- ↑ Marrosu F, Barberini L, Puligheddu M, et al. Combined EEG/fMRI recording in musicogenic epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2009; 84: 77–81

- ↑ Tayah TF, Abou-Khalil B, Gilliam FG et al. Musicogenic seizures can arise from multiple temporal lobe foci: intracranial EEG analyses of three patients. Epilepsia 2006; 47: 1402–1406

- ↑ Hoppner AC, Dehnicke C, Kerling F, Schmitt FC. Zur Neurobiologie musikogener Epilepsien – resektiv operierte Patienten und funktionelle MRT-Untersuchungen. Z Epileptol 2016; 29: 7–15