An African American is a citizen or resident of the United States who has origins in any of the black populations of Africa. African American-related topics include:

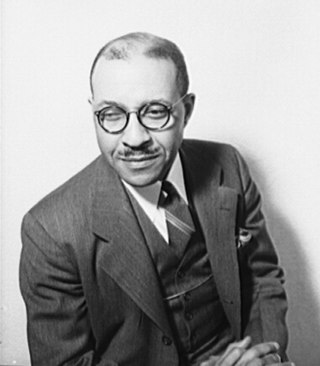

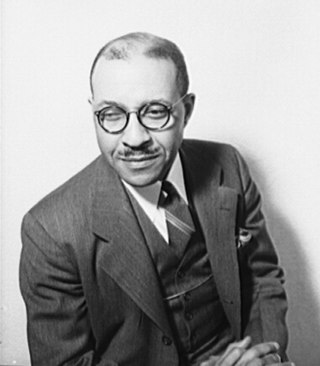

Arthur Wergs Mitchell, Sr., was a U.S. Representative from Illinois. For his entire congressional career from 1935 to 1943, he was the only African American in Congress. Mitchell was the first African American to be elected to the United States Congress as a Democrat—he defeated and succeeded Oscar De Priest, a black Republican.

Oscar Stanton De Priest was an American politician and civil rights advocate from Chicago. A member of the Illinois Republican Party, he was the first African American to be elected to Congress in the 20th century. During his three terms, he was the only African American serving in Congress. He served as a U.S. Representative from Illinois's 1st congressional district from 1929 to 1935. De Priest was also the first African-American U.S. Representative from outside the southern states and the first since the exit of North Carolina representative George Henry White from Congress in 1901.

African-American art is a broad term describing visual art created by African Americans. The range of art they have created, and are continuing to create, over more than two centuries is as varied as the artists themselves. Some have drawn on cultural traditions in Africa, and other parts of the world, for inspiration. Others have found inspiration in traditional African-American plastic art forms, including basket weaving, pottery, quilting, woodcarving and painting, all of which are sometimes classified as "handicrafts" or "folk art".

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

George Samuel Schuyler was an American writer, journalist, and social commentator known for his conservatism after he had initially supported socialism.

This is a timeline of African-American history, the part of history that deals with African Americans.

Oscar Brown Jr. was an American singer, songwriter, playwright, poet, civil rights activist, and actor. Aside from his career, Brown ran unsuccessfully for office in both the Illinois state legislature and the U.S. Congress. Brown wrote many songs, 12 albums, and more than a dozen musical plays.

The history of African Americans in Chicago or Black Chicagoans dates back to Jean Baptiste Point du Sable’s trading activities in the 1780s. Du Sable, the city's founder, was Haitian of African and French descent. Fugitive slaves and freedmen established the city's first black community in the 1840s. By the late 19th century, the first black person had been elected to office.

Charles Spurgeon Johnson was an American sociologist and college administrator, the first black president of historically black Fisk University, and a lifelong advocate for racial equality and the advancement of civil rights for African Americans and all ethnic minorities. He preferred to work collaboratively with liberal white groups in the South, quietly as a "sideline activist," to get practical results.

Harry Haywood was an American political activist who was a leading figure in both the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). His goal was to connect the political philosophy of the Communist Party with the issues of race.

The Reverse Underground Railroad is the name given, sardonically, to the pre-American Civil War practice of kidnapping in free states not only fugitive slaves but free blacks as well, transporting them to slave states, and selling them as slaves, or occasionally getting a reward for return of a fugitive. Those who used the term were pro-slavery and angered at an "underground railroad" helping slaves escape. Also, the so-called "reverse underground railroad" had incidents but not a network, and its activities did not always take place in secret. Rescues of blacks being kidnapped were unusual.

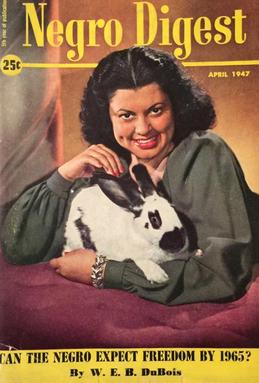

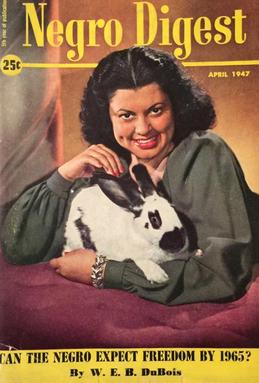

The Negro Digest, later renamed Black World, was a magazine for the African-American market. Founded in November 1942 by publisher John H. Johnson of Johnson Publishing Company, Negro Digest was first published locally in Chicago, Illinois. The magazine was similar to the Reader's Digest but aimed to cover positive stories about the African-American community. The Negro Digest ceased publication in 1951 but returned in 1961. In 1970, Negro Digest was renamed Black World and continued to appear until April 1976.

Oscar Brown Sr. was a prominent Chicago businessman, lawyer and community activist. He was the father of Oscar Brown Jr.

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves around the social, political, and economic empowerment of black communities and people, especially to resist their cultural assimilation into white culture, and maintain a distinct black identity.

African-American self-determination refers to efforts to secure self-determination for African-Americans and related peoples in North America. It often intersects with the historic Back-to-Africa movement and general Black separatism, but also manifests in present and historic demands for self-determination on North American soil, ranging from autonomy to independence. The freedom to make whatever choices as a free American, and willfulness to do for self are often a key demand for advocates of African-American self-determination.

The American Negro Exposition, also known as the Black World's Fair and the Diamond Jubilee Exposition, was a world's fair held in Chicago from July until September in 1940, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the end of slavery in the United States at the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865.

Ira Helser Latimer (1906–1985) was an educator, missionary, activist, and lawyer who advocated for civil rights and equal accommodation for African Americans in Chicago. Minneapolis mayor Thomas Erwin Latimer was his father.

George T. Kersey was a state legislator in Illinois. He was a Republican who served in the Illinois House of Representatives from 1923 to 1925 and from 1927 to 1931. He was an undertaker. The New York Public Library has a photograph of him. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote to him requesting a biographical account of Kersey's life.

Cavalcade of the American Negro is a grouping of related artworks collaboratively created by employees of the WPA-funded Illinois Writers' Project and the Federal Art Project for the 1940 American Negro Exposition, a world's fair-style event celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Emancipation of enslaved people in the United States.