The Gulf of Tonkin incident was an international confrontation that led to the United States engaging more directly in the Vietnam War. It involved both a proven confrontation on August 2, 1964, carried out by North Vietnamese forces in response to covert operations in the coastal region of the gulf, and a second, claimed confrontation on August 4, 1964, between North Vietnamese and United States ships in the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin. Originally American claims blamed North Vietnam for both attacks. Later investigation revealed that the second attack never happened; the American claim is that it was based mostly on erroneously interpreted communications intercepts.

Robert Strange McNamara was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the longest serving Secretary of Defense, having remained in office over seven years. He played a major role in promoting the United States' involvement in the Vietnam War. McNamara was responsible for the institution of systems analysis in public policy, which developed into the discipline known today as policy analysis.

McGeorge "Mac" Bundy was an American academic who served as the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 through 1966. He was president of the Ford Foundation from 1966 through 1979. Despite his career as a foreign-policy intellectual, educator, and philanthropist, he is best remembered as one of the chief architects of the United States' escalation of the Vietnam War during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

The Pentagon Papers, officially titled Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force, is a United States Department of Defense history of the United States' political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967. Released by Daniel Ellsberg, who had worked on the study, they were first brought to the attention of the public on the front page of The New York Times in 1971. A 1996 article in The New York Times said that the Pentagon Papers had demonstrated, among other things, that the Johnson Administration had "systematically lied, not only to the public but also to Congress."

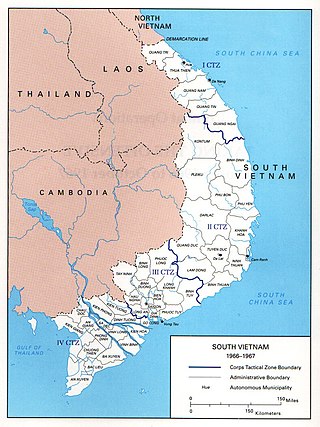

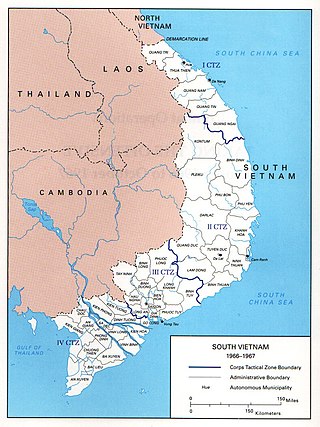

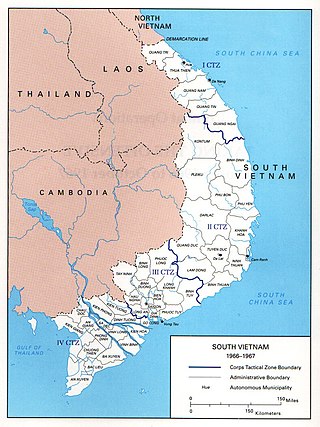

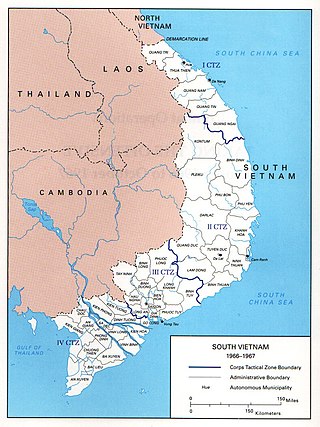

Hearts and Minds or winning hearts and minds refers to the strategy and programs used by the governments of Vietnam and the United States during the Vietnam War to win the popular support of the Vietnamese people and to help defeat the Viet Cong insurgency. Pacification is the more formal term for winning hearts and minds. In this case, however, it was also defined as the process of countering the insurgency. Military, political, economic, and social means were used to attempt to establish or reestablish South Vietnamese government control over rural areas and people under the influence of the Viet Cong. Some progress was made in the 1967–1971 period by the joint military-civilian organization called CORDS, but the character of the war changed from a guerrilla war to a conventional war between the armies of South and North Vietnam. North Vietnam won in 1975.

United States involvement in the Vietnam War began shortly after the end of World War II in Asia, first in an extremely limited capacity and escalating over a period of 20 years. The U.S. military presence peaked in April 1969, with 543,000 American combat troops stationed in Vietnam. By the conclusion of the United States's involvement in 1973, over 3.1 million Americans had been stationed in Vietnam.

The Buddhist crisis was a period of political and religious tension in South Vietnam between May and November 1963, characterized by a series of repressive acts by the South Vietnamese government and a campaign of civil resistance, led mainly by Buddhist monks.

The Taylor-Rostow Report was a report prepared in November 1961 on the situation in Vietnam in relation to Vietcong operations in South Vietnam. The report was written by General Maxwell Taylor, military representative to President John F. Kennedy, and Deputy National Security Advisor W.W. Rostow. Kennedy sent Taylor and Rostow to Vietnam in October 1961 to assess the deterioration of South Vietnam’s military position and the government's morale. The report called for improved training of Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops, an infusion of American personnel into the South Vietnamese government and army, greater use of helicopters in counterinsurgency missions against North Vietnamese communists, consideration of bombing the North, and the commitment of 6,000-8,000 U.S. combat troops to Vietnam, albeit initially in a logistical role. The document was significant in that it seriously escalated the Kennedy Administration's commitment to Vietnam. It was also seen historically as having misdiagnosed the root of the Vietnam conflict as primarily a military rather than a political problem.

DEPTEL 243, also known as Telegram 243, the August 24 cable or most commonly Cable 243, was a high-profile message sent on August 24, 1963, by the United States Department of State to Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., the US ambassador to South Vietnam. The cable came in the wake of the midnight raids on August 21 by the regime of Ngô Đình Diệm against Buddhist pagodas across the country, in which hundreds were believed to have been killed. The raids were orchestrated by Diệm's brother Ngô Đình Nhu and precipitated a change in US policy. The cable declared that Washington would no longer tolerate Nhu remaining in a position of power and ordered Lodge to pressure Diệm to remove his brother. It said that if Diệm refused, the Americans would explore the possibility for alternative leadership in South Vietnam. In effect, the cable authorized Lodge to give the green light to Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) officers to launch a coup against Diệm if he did not willingly remove Nhu from power. The cable marked a turning point in US-Diem relations and was described in the Pentagon Papers as "controversial." The historian John M. Newman described it as "the single most controversial cable of the Vietnam War."

The Krulak–Mendenhall mission was a fact-finding expedition dispatched by the Kennedy administration to South Vietnam in early September 1963. The stated purpose of the expedition was to investigate the progress of the war by the South Vietnamese regime and its US military advisers against the Viet Cong insurgency. The mission was led by Victor Krulak and Joseph Mendenhall. Krulak was a major general in the United States Marine Corps, while Mendenhall was a senior Foreign Service Officer experienced in dealing with Vietnamese affairs.

The McNamara–Taylor mission was a 10-day fact-finding expedition to South Vietnam in September 1963 by the Kennedy administration to review progress in the battle by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and its American advisers against the communist insurgency of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. The mission was led by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and General Maxwell D. Taylor, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Joseph Abraham Mendenhall was a United States State Department official, known for his advisory work during the Kennedy administration on policy towards Vietnam and Laos. He was best known for his participation in the Krulak Mendenhall mission to South Vietnam in 1963 with General Victor Krulak. Their vastly divergent conclusions led U.S. President John F. Kennedy to ask if they had visited the same country. Mendenhall continued his work in the Indochina region after Lyndon B. Johnson assumed the presidency in wake of Kennedy's assassination.

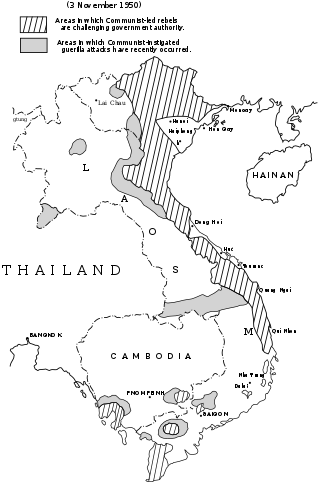

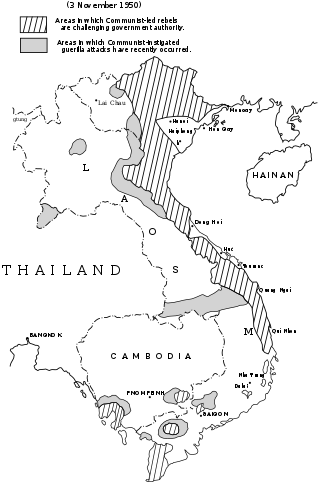

The 1954 to 1959 phase of the Vietnam War was the era of the two nations. Coming after the First Indochina War, this period resulted in the military defeat of the French, a 1954 Geneva meeting that partitioned Vietnam into North and South, and the French withdrawal from Vietnam, leaving the Republic of Vietnam regime fighting a communist insurgency with USA aid. During this period, North Vietnam recovered from the wounds of war, rebuilt nationally, and accrued to prepare for the anticipated war. In South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm consolidated power and encouraged anti-communism. This period was marked by U.S. support to South Vietnam before Gulf of Tonkin, as well as communist infrastructure-building.

The 1959 to 1963 phase of the Vietnam War started after the North Vietnamese had made a firm decision to commit to a military intervention in the guerrilla war in the South Vietnam, a buildup phase began, between the 1959 North Vietnamese decision and the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which led to a major US escalation of its involvement. Vietnamese communists saw this as a second phase of their revolution, the US now substituting for the French.

During the Cold War in the 1960s, the United States and South Vietnam began a period of gradual escalation and direct intervention referred to as the joint warfare in South Vietnam in the Vietnam War. At the start of the decade, United States aid to South Vietnam consisted largely of supplies with approximately 900 military observers and trainers. After the assassination of both Ngo Dinh Diem and John F. Kennedy close to the end of 1963 and Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 and amid continuing political instability in the South, the Lyndon Johnson Administration made a policy commitment to safeguard the South Vietnamese regime directly. The American military forces and other anti-communist SEATO countries increased their support, sending large scale combat forces into South Vietnam; at its height in 1969, slightly more than 400,000 American troops were deployed. The People's Army of Vietnam and the allied Viet Cong fought back, keeping to countryside strongholds while the anti-communist allied forces tended to control the cities. The most notable conflict of this era was the 1968 Tet Offensive, a widespread campaign by the communist forces to attack across all of South Vietnam; while the offensive was largely repelled, it was a strategic success in seeding doubt as to the long-term viability of the South Vietnamese state. This phase of the war lasted until the election of Richard Nixon and the change of U.S. policy to Vietnamization, or ending the direct involvement and phased withdrawal of U.S. combat troops and giving the main combat role back to the South Vietnamese military.

The year 1961 saw a new American president, John F. Kennedy, attempt to cope with a deteriorating military and political situation in South Vietnam. The Viet Cong (VC) with assistance from North Vietnam made substantial gains in controlling much of the rural population of South Vietnam. Kennedy expanded military aid to the government of President Ngô Đình Diệm, increased the number of U.S. military advisors in South Vietnam, and reduced the pressure that had been exerted on Diệm during the Eisenhower Administration to reform his government and broaden his political base.

The defeat of the South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in a battle in January set off a furious debate in the United States on the progress being made in the war against the Viet Cong (VC) in South Vietnam. Assessments of the war flowing into the higher levels of the U.S. government in Washington, D.C. were wildly inconsistent, some citing an early victory over the VC, others a rapidly deteriorating military situation. Some senior U.S. military officers and White House officials were optimistic; civilians of the Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), junior military officers, and the media were decidedly less so. Near the end of the year, U.S. leaders became more pessimistic about progress in the war.

The United States foreign policy during the presidency of John F. Kennedy from 1961 to 1963 included John F. Kennedy's diplomatic and military initiatives in Western Europe, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, all conducted amid considerable Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Kennedy deployed a new generation of foreign policy experts, dubbed "the best and the brightest". In his inaugural address Kennedy encapsulated his Cold War stance: "Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate".

National Security Action Memorandum Number 263 (NSAM-263) was a national security directive approved on 11 October 1963 by United States President John F. Kennedy. The NSAM approved recommendations by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Maxwell Taylor. McNamara and Taylor's recommendations included an appraisal that "great progress" was being made in the Vietnam War against Viet Cong insurgents, that 1,000 military personnel could be withdrawn from South Vietnam by the end of 1963, and that a "major part of the U.S. military task can be completed by the end of 1965." The U.S. at this time had more than 16,000 military personnel in South Vietnam.

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the Southeast Asia Resolution, Pub. L. 88–408, 78 Stat. 384, enacted August 10, 1964, was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964, in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident.