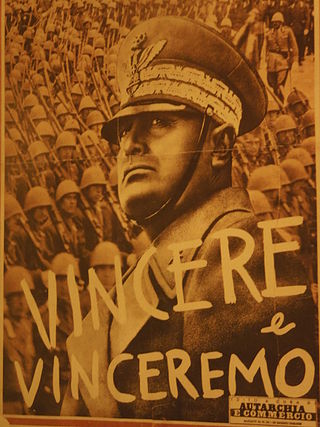

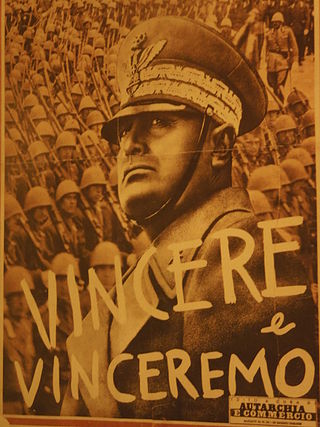

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultranationalist political ideology and movement, characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hierarchy, subordination of individual interests for the perceived good of the nation or race, and strong regimentation of society and the economy.

Neo-fascism is a post–World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration sentiment, as well as opposition to liberal democracy, social democracy, parliamentarianism, liberalism, Marxism, capitalism, communism, and socialism. As with classical fascism, it proposes a Third Position as an alternative to market capitalism.

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and racial supremacy, to attack racial and ethnic minorities, and in some cases to create a fascist state.

Francis Parker Yockey was an American fascist and pan-Europeanist ideologue. A lawyer, he is known for his neo-Spenglerian book Imperium: The Philosophy of History and Politics, published in 1948 under the pen name Ulick Varange, which called for a neo-Nazi European empire.

The German American Bund, or the German American Federation, was a German-American Nazi organization which was established in 1936 as a successor to the Friends of New Germany. The organization chose its new name in order to emphasize its American credentials after the press accused it of being unpatriotic. The Bund was allowed to consist only of American citizens of German descent. Its main goal was to promote a favorable view of Nazi Germany.

Clerical fascism is an ideology that combines the political and economic doctrines of fascism with clericalism. The term has been used to describe organizations and movements that combine religious elements with fascism, receive support from religious organizations which espouse sympathy for fascism, or fascist regimes in which clergy play a leading role.

Strasserism is an ideological strand of Nazism which adheres to revolutionary nationalism and to economic antisemitism, which conditions are to be achieved with radical, mass-action and worker-based politics that are more aggressive than the politics of the Hitlerite leaders of the Nazi Party. Named after brothers Gregor Strasser and Otto Strasser, the ideology of Strasserism is a type of Third Position, right-wing politics in opposition to Communism and to Hitlerite Nazism.

The Third Position is a set of neo-fascist political ideologies that were first described in Western Europe following the Second World War. Developed in the context of the Cold War, it developed its name through the claim that it represented a third position between the capitalism of the Western Bloc and the communism of the Eastern Bloc.

Fascist has been used as a pejorative epithet against a wide range of people, political movements, governments, and institutions since the emergence of fascism in Europe in the 1920s. Political commentators on both the Left and the Right accused their opponents of being fascists, starting in the years before World War II. In 1928, the Communist International labeled their social democratic opponents as social fascists, while the social democrats themselves as well as some parties on the political right accused the Communists of having become fascist under Joseph Stalin's leadership. In light of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, The New York Times declared on 18 September 1939 that "Hitlerism is brown communism, Stalinism is red fascism." Later, in 1944, the anti-fascist and socialist writer George Orwell commented on Tribune that fascism had been rendered almost meaningless by its common use as an insult against various people, and argued that in England the word fascist had become a synonym for bully.

The history of fascist ideology is long and it draws on many sources. Fascists took inspiration from sources as ancient as the Spartans for their focus on racial purity and their emphasis on rule by an elite minority. Fascism has also been connected to the ideals of Plato, though there are key differences between the two. Fascism styled itself as the ideological successor to Rome, particularly the Roman Empire. From the same era, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's view on the absolute authority of the state also strongly influenced fascist thinking. The French Revolution was a major influence insofar as the Nazis saw themselves as fighting back against many of the ideas which it brought to prominence, especially liberalism, liberal democracy and racial equality, whereas on the other hand, fascism drew heavily on the revolutionary ideal of nationalism. The prejudice of a "high and noble" Aryan culture as opposed to a "parasitic" Semitic culture was core to Nazi racial views, while other early forms of fascism concerned themselves with non-racialized conceptions of the nation.

The "Manifesto of Race", otherwise referred to as the Charter of Race or the Racial Manifesto, was an Italian manifesto promulgated by the government of Benito Mussolini on 14 July 1938. Its promulgation was followed by the enactment, in October 1938, of the Racial Laws in Fascist Italy and the Italian Empire.

Movimiento Nacional Socialista de Chile was a political movement in Chile, during the Presidential Republic Era, which initially supported the ideas of Adolf Hitler, although it later moved towards a more local form of fascism. They were commonly known as Nacistas.

This is a list of topics related to racism:

Fascist movements in Europe were the set of various fascist ideologies which were practiced by governments and political organizations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist movements, influenced by Italian Fascism, subsequently emerged across Europe. Among the political doctrines which are identified as ideological origins of fascism in Europe are the combining of a traditional national unity and revolutionary anti-democratic rhetoric which was espoused by the integral nationalist Charles Maurras and the revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel.

Fascism has a long history in North America, with the earliest movements appearing shortly after the rise of fascism in Europe.

Nazism, formally National Socialism, is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power in 1930s Europe, it was frequently referred to as Hitlerism. The later related term "neo-Nazism" is applied to other far-right groups with similar ideas which formed after the Second World War when the Third Reich collapsed.

Antisemitism is the practice of showing hostility toward or discrimination against Jews as a religious, ethnic, or racial group. In Argentina antisemitism has been around since Spanish colonization in the sixteenth century, and has continued to the present day. In the twentieth century antisemitism in Argentina was particularly pervasive, especially in the World War II and post-World War II eras. In these eras Argentine antisemitism adopted Nazi antisemitism, and blended it with religious (Catholic) hostility, which allowed vehement antisemitism in Argentina to persist well into the 1970s and 1980s.