Leishmaniasis is a wide array of clinical manifestations caused by parasites of the Trypanosomatida genus Leishmania. It is generally spread through the bite of phlebotomine sandflies, Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia, and occurs most frequently in the tropics and sub-tropics of Africa, Asia, the Americas, and southern Europe. The disease can present in three main ways: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral. The cutaneous form presents with skin ulcers, while the mucocutaneous form presents with ulcers of the skin, mouth, and nose. The visceral form starts with skin ulcers and later presents with fever, low red blood cell count, and enlarged spleen and liver.

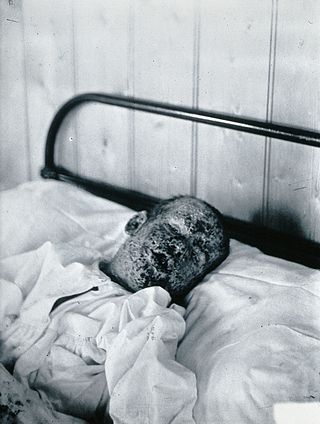

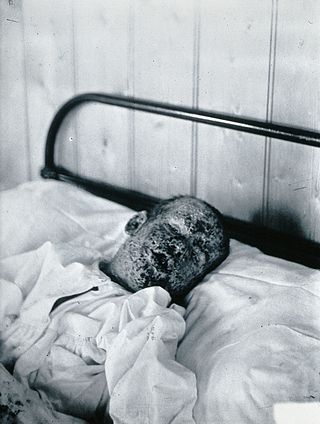

Yaws is a tropical infection of the skin, bones, and joints caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum pertenue. The disease begins with a round, hard swelling of the skin, 2 to 5 cm in diameter. The center may break open and form an ulcer. This initial skin lesion typically heals after 3–6 months. After weeks to years, joints and bones may become painful, fatigue may develop, and new skin lesions may appear. The skin of the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet may become thick and break open. The bones may become misshapen. After 5 years or more, large areas of skin may die, leaving scars.

Wuchereria bancrofti is a filarial (arthropod-borne) nematode (roundworm) that is the major cause of lymphatic filariasis. It is one of the three parasitic worms, together with Brugia malayi and B. timori, that infect the lymphatic system to cause lymphatic filariasis. These filarial worms are spread by a variety of mosquito vector species. W. bancrofti is the most prevalent of the three and affects over 120 million people, primarily in Central Africa and the Nile delta, South and Central America, the tropical regions of Asia including southern China, and the Pacific islands. If left untreated, the infection can develop into lymphatic filariasis. In rare conditions, it also causes tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. No vaccine is commercially available, but high rates of cure have been achieved with various antifilarial regimens, and lymphatic filariasis is the target of the World Health Organization Global Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis with the aim to eradicate the disease as a public-health problem by 2020. However, this goal was not met by 2020.

Helminthiasis, also known as worm infection, is any macroparasitic disease of humans and other animals in which a part of the body is infected with parasitic worms, known as helminths. There are numerous species of these parasites, which are broadly classified into tapeworms, flukes, and roundworms. They often live in the gastrointestinal tract of their hosts, but they may also burrow into other organs, where they induce physiological damage.

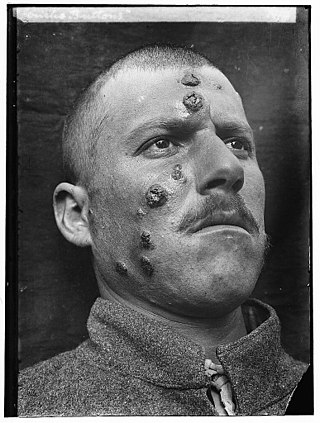

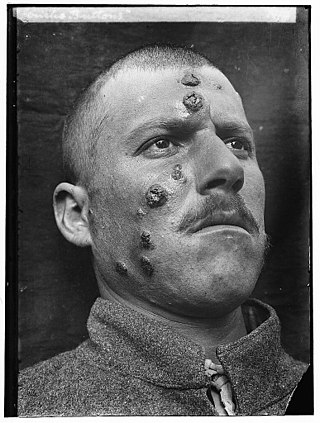

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form of leishmaniasis affecting humans. It is a skin infection caused by a single-celled parasite that is transmitted by the bite of a phlebotomine sand fly. There are about thirty species of Leishmania that may cause cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Podoconiosis, also known as nonfilarial elephantiasis, is a disease of the lymphatic vessels of the lower extremities that is caused by chronic exposure to irritant soils. It is the second most common cause of tropical lymphedema after lymphatic filariasis, and it is characterized by prominent swelling of the lower extremities, which leads to disfigurement and disability. Methods of prevention include wearing shoes and using floor coverings. Mainstays of treatment include daily foot hygiene, compression bandaging, and when warranted, surgery of overlying nodules.

Lymphatic filariasis is a human disease caused by parasitic worms known as filarial worms. Usually acquired in childhood, it is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide, impacting over a hundred million people and manifesting itself in a variety of severe clinical pathologies While most cases have no symptoms, some people develop a syndrome called elephantiasis, which is marked by severe swelling in the arms, legs, breasts, or genitals. The skin may become thicker as well, and the condition may become painful. Affected people are often unable to work and are often shunned or rejected by others because of their disfigurement and disability.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a diverse group of tropical infections that are common in low-income populations in developing regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. They are caused by a variety of pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and parasitic worms (helminths). These diseases are contrasted with the "big three" infectious diseases, which generally receive greater treatment and research funding. In sub-Saharan Africa, the effect of neglected tropical diseases as a group is comparable to that of malaria and tuberculosis. NTD co-infection can also make HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis more deadly.

The eradication of infectious diseases is the reduction of the prevalence of an infectious disease in the global host population to zero.

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) is a complication of visceral leishmaniasis (VL); it is characterised by a macular, maculopapular, and nodular rash in a patient who has recovered from VL and who is otherwise well. The rash usually starts around the mouth from where it spreads to other parts of the body depending on severity.

Mycetoma is a chronic infection in the skin caused by either bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma), typically resulting in a triad of painless firm skin lumps, the formation of weeping sinuses, and a discharge that contains grains. 80% occur in feet.

Leprosy currently affects approximately a quarter of a million people throughout the world, with the majority of these cases being reported from India.

The London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases was a collaborative disease eradication programme launched on 30 January 2012 in London. It was inspired by the World Health Organization roadmap to eradicate or prevent transmission for neglected tropical diseases by the year 2020. Officials from WHO, the World Bank, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the world's 13 leading pharmaceutical companies, and government representatives from US, UK, United Arab Emirates, Bangladesh, Brazil, Mozambique and Tanzania participated in a joint meeting at the Royal College of Physicians to launch this project. The meeting was spearheaded by Margaret Chan, Director-General of WHO, and Bill Gates, Co-Chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Mission Rabies is a charity that was initially founded as an initiative by Worldwide Veterinary Service (WVS), a United Kingdom-based charity group that assists animals. Mission Rabies has a One Health approach driven by research to eliminate dog bite transmitted rabies. Launched in September 2013 with a mission to vaccinate 50,000 dogs against rabies across India, Mission Rabies teams have since then vaccinated 968,287 dogs and educated 2,330,597 children in dog bite prevention in rabies endemic countries.

Kala azar in India refers to the special circumstances of the disease kala azar as it exists in India. Kala azar is a major health problem in India with an estimated 146,700 new cases per year as of 2012. In the disease a parasite causes sickness after migrating to internal organs such as the liver, spleen and bone marrow. If left untreated the disease almost always results in the death. Signs and symptoms include fever, weight loss, fatigue, anemia, and substantial swelling of the liver and spleen.

The Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF) is a World Health Organization project to eradicate the Filarioidea worms which cause the disease lymphatic filariasis and also treat the people who already have the infection.

The eradication of lymphatic filariasis is the ongoing attempt to eradicate the Filarioidea worms which cause the disease lymphatic filariasis and also treat the people who already have the infection.

Lymphatic filariasis in India refers to the presence of the disease lymphatic filariasis in India and the social response to the disease. In India, 99% of infections come from a type of mosquito spreading a type of worm through a mosquito bite. The treatment plan provides 400 million people in India with medication to eliminate the parasite. About 50 million people in India were carrying the worm as of the early 2010s, which is 40% of all the cases in the world. In collaboration with other countries around the world, India is participating in a global effort to eradicate lymphatic filariasis. If the worm is eliminated from India then the disease could be permanently eradicated. In October 2019 the Union health minister Harsh Vardhan said that India's current plan is on schedule to eradicate filariasis by 2021.

Ahmed Mohamed El Hassan FRCP FTWAS was a Sudanese professor of pathology.

The Kigali Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases is a global health project that aims to mobilise political and financial resources for the control and eradication of infectious diseases, the so-called neglected tropical diseases due to different parasitic infections. Launched by the Uniting to Combat Neglected Tropical Diseases on 27 January 2022, it was the culmination and join commitment declared at the Kigali Summit on Malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) hosted by the Government of Rwanda at its capital city Kigali on 23 June 2022.