Founding

The New-York Manumission Society was founded in 1785, under the full name "The New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting Such of Them as Have Been, or May be Liberated". The organization originally comprised a few dozen friends, many of whom were themselves slaveholders at the time. The members were motivated in part by the rampant kidnapping of free blacks from the streets of New York, who were then sold into slavery. [2] Several of the members were Quakers. [2]

Robert Troup presided over the first meeting, [3] which was held on January 25, 1785, at the home of John Simmons, who had space for the nineteen men in attendance since he kept an inn. Troup, who owned two slaves, and Melancton Smith were appointed to draw up rules, and John Jay, who owned five slaves, was elected as the Society's first president. [2]

At the second meeting, held on February 4, 1785, the group grew to 31 members, including Alexander Hamilton. [1] [2]

The Society formed a ways-and-means committee to deal with the difficulty that more than half of the members, including Troup and Jay, owned slaves (mostly a few domestic servants per household). The committee reported a plan for gradual emancipation: members would free slaves then younger than 28 when they reached the age of 35, slaves between 28 and 38 in seven years' time, and slaves over 45 immediately. This was voted down, and the committee was dissolved. [2]

Activities

Lobbying and boycotts

John Jay had been a prominent leader in the antislavery cause since 1777, when he drafted a state law to abolish slavery in New York. The draft failed, as did a second attempt in 1785. In 1785, all state legislators except one voted for some form of gradual emancipation. However, they did not agree on what civil rights would be given to the slaves once they were freed.

Jay brought prominent political leaders into the Society, and also worked closely with Aaron Burr, later head of the Democratic-Republicans in New York. The Society started a petition against slavery, which was signed by almost all the politically prominent men in New York, of all parties and led to a bill for gradual emancipation. Burr, in addition to supporting the bill, made an amendment for immediate abolition, which was voted down.

The Society was instrumental in having a state law passed in 1785 prohibiting the sale of slaves imported into the state, and making it easy for slaveholders to manumit slaves either by a registered certificate or by will. In 1788 the purchase of slaves for removal to another state was forbidden; they were allowed trial by jury "in all capital cases;" and the earlier laws about slaves were simplified and restated. The emancipation of slaves by the Quakers was legalized in 1798. At that date, there were still about 33,000 slaves statewide. [4]

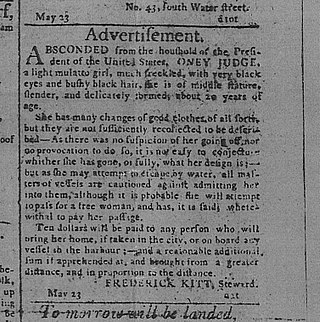

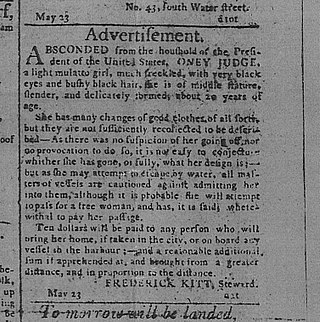

The Society organized boycotts against New York merchants and newspaper owners involved in the slave trade. The Society had a special committee of militants who visited newspaper offices to warn publishers against accepting advertisements for the purchase or sale of slaves.

Another committee kept a list of people who were involved in the slave trade, and urged members to boycott anyone listed. According to historian Roger Kennedy:

Those [blacks] who remained in New York soon discovered that until the Manumission Society was organized, things had gotten worse, not better, for blacks. Despite the efforts of Burr, Hamilton, and Jay, the slave importers were busy. There was a 23 percent increase in slaves and a 33 percent increase in slaveholders in New York City in the 1790s. [5]

Helping free Blacks

In 1806, the society obtained a court writ forbidding a sloop from leaving the port with three free blacks on board, who had been seized to sell in another state as enslaved. [6]

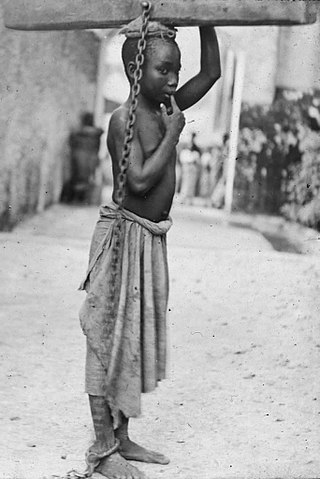

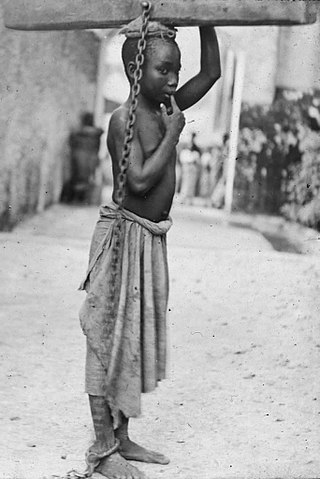

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate slaves around the world.

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves by their owners. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that the most widely used term is gratuitous manumission, "the conferment of freedom on the enslaved by enslavers before the end of the slave system".

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn people of color and emancipated slaves to the continent of Africa. It was modeled on an earlier British colonization in Africa, which had sought to resettle London's "black poor".

Austin Steward was an African-American abolitionist and author. He was born a slave in Virginia then moved at age 7 with the Helm household to New York State in 1800. The household settled in the town of Bath, New York, in 1803. He escaped slavery at about age 21, settling in Rochester, New York, and then British North America. His autobiography, Twenty-Two Years a Slave, was published in 1857.

Cadwallader David Colden was an American politician who served as the 54th Mayor of New York City and a U.S. Representative from New York.

Compensated emancipation was a method of ending slavery, under which the enslaved person's owner received compensation from the government in exchange for manumitting the slave. This could be monetary, and it could allow the owner to retain the slave for a period of labor as an indentured servant. Cash compensation rarely was equal to the slave's market value.

The history of George Washington and slavery reflects Washington's changing attitude toward the ownership of human beings. The preeminent Founding Father of the United States and a hereditary slaveowner, Washington became increasingly uneasy with it. Slavery was then a longstanding institution dating back over a century in Virginia where he lived; it was also longstanding in other American colonies and in world history. Washington's will immediately freed one of his slaves, and required his remaining 123 slaves to serve his wife and be freed no later than her death, so they ultimately became free one year after his own death.

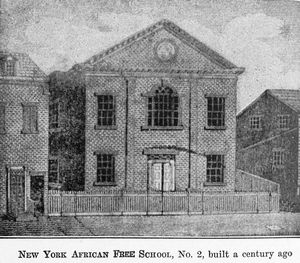

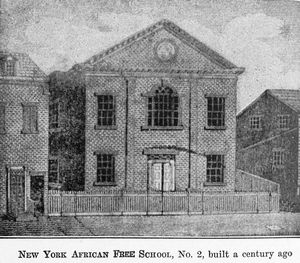

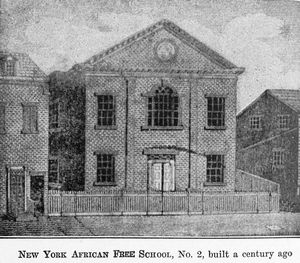

The African Free School was a school for children of slaves and free people of color in New York City. It was founded by members of the New York Manumission Society, including Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, on November 2, 1787. Many of its alumni became leaders in the African-American community in New York.

The trafficking of enslaved Africans to what became New York began as part of the Dutch slave trade. The Dutch West India Company trafficked eleven enslaved Africans to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction held in New Amsterdam in 1655. With the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies, more than 42% of New York City households enslaved African people by 1703, often as domestic servants and laborers. Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Enslaved Africans were also used in farming on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley, as well as the Mohawk Valley region.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Robert Troup was a soldier in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of New York. He participated in the Battles of Saratoga and was present at the surrender of British General John Burgoyne.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

Lemmon v. New York, or Lemmon v. The People (1860), popularly known as the Lemmon Slave Case, was a freedom suit initiated in 1852 by a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. The petition was granted by the Superior Court in New York City, a decision upheld by the New York Court of Appeals, New York's highest court, in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War.

An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the Fifth Pennsylvania General Assembly on 1 March 1780, prescribed an end for slavery in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the United States. It was the first slavery abolition act in the course of human history to be adopted by an elected body.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by slaves against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Betto Douglas was a slave on St. Kitts, at the time a British Colony. What is known of her life illuminates the practice slavery in the Caribbean and the efforts of abolitionist societies to free them. Douglas is an iconic figure of resistance to slavery in the country and her story is featured in the National Museum of Saint Kitts and Nevis. In Britain, she is included on the initial slave register for St. Kitts and kept in the Central Slave Registries at the British National Archives, which are enrolled in the UNESCO Memory of the World Registry.

Lt. Abijah Hammond, Jr was an American artillery officer in the Revolutionary War in the Continental line. After the war, he became a merchant and real estate investor active in various endeavors important to the development of New York.