The Treaty of Lausanne was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflict that had originally existed between the Ottoman Empire and the Allied French Republic, British Empire, Kingdom of Italy, Empire of Japan, Kingdom of Greece, and the Kingdom of Romania since the onset of World War I. The original text of the treaty is in French. It was the result of a second attempt at peace after the failed and unratified Treaty of Sèvres, which aimed to divide Ottoman lands. The earlier treaty had been signed in 1920, but later rejected by the Turkish national movement who fought against its terms. As a result of Greco-Turkish War, İzmir was retrieved and Armistice of Mudanya was signed in October 1922. It provided for the Greek-Turkish population exchange and allowed unrestricted civilian passage through the Turkish Straits.

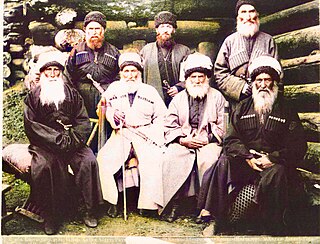

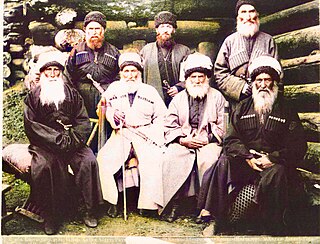

Circassia was a country and a historical region in the North Caucasus along the northeast shore of the Black Sea. It was destroyed and devastated after the Russian-Circassian war (1763–1864) and 90% of the Circassian people were either exiled from the region or massacred in the Circassian genocide.

The Karachays are a Turkic people of the North Caucasus, mostly situated in the Russian Karachay–Cherkess Republic.

The Circassians are an indigenous ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia in the North Caucasus. As a consequence of the Circassian genocide, which was perpetrated by the Russian Empire in the 19th century during the Russo-Circassian War, most Circassians were exiled from their homeland in Circassia to modern-day Turkey and the rest of the Middle East, where the majority of them are concentrated today.

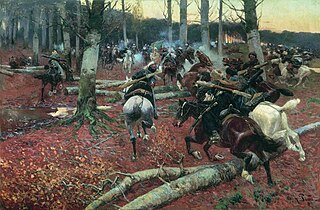

The Caucasian War was an invasion of the Caucasus by the Russian Empire, which resulted in Russia's annexation of the areas of the North Caucasus, and the ethnic cleansing of Circassians. It consisted of a series of military actions waged by the Empire against the native peoples of the Caucasus including the Chechens, Adyghe, Abkhaz–Abaza, Ubykhs, Kumyks and Dagestanians as Russia sought to expand. Among the Muslims, resistance to the Russians was described as jihad.

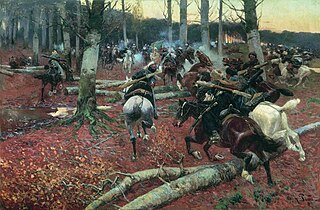

The Circassian genocide, known as the Tsitsekun by the Circassians, was the Russian Empire's systematic mass murder, ethnic cleansing, and expulsion of 80–97% of the Muslim Circassian population, around 800,000–1,500,000 people, from their homeland Circassia in the aftermath of the Russo-Circassian War (1763–1864). The majority of Circassians were killed or exiled, though a minority resettled in swamps; others who accepted Russification remained. It has been reported that during the events, the Russian-Cossack forces used various methods, such as tearing the bellies of pregnant women. Russian generals such as Grigory Zass described the Circassians as "subhuman filth", and justified their killing and use in scientific experiments, also allowing their soldiers to rape women.

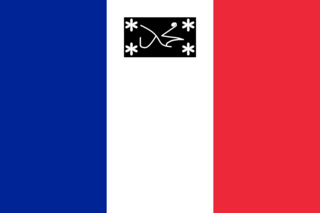

The Circassian flag is the national flag of the Circassians. It consists of a green field charged with twelve gold stars, nine forming an arc and three horizontal, also charged with three crossed arrows in the center.

The Russo-Circassian War was the military conflict between Circassia and Russia, starting in 1763 with the Russian Empire's attempts to quickly annex Circassia, followed by the Circassian rejection of annexation; ending 101 years later with the last army of Circassia defeated on 21 May 1864, making it exhausting and casualty heavy for both sides as well as being the longest war Russia ever waged in history. The end of the war saw the Circassian genocide take place in which Imperial Russia aimed to systematically destroy the Circassian people where several atrocities were committed by the Russian forces and up to 1,500,000 Circassians were either killed or expelled to the Ottoman Empire, creating the Circassian diaspora.

Circassian nationalism is the desire among Circassians worldwide to preserve their culture, save their language from extinction, raise awareness about the Circassian genocide, return to Circassia and establish an independent or completely autonomous Circassian state in its pre-Russian invasion borders.

Circassians in Israel are Israelis who are ethnic Circassians. They are a branch of the Circassian diaspora, which was formed as a consequence of the 19th-century Circassian genocide that was carried out by the Russian Empire during the Russo-Circassian War; Circassians are a Northwest Caucasian ethnic group who natively speak the Circassian languages and originate from the historical country-region of Circassia in the North Caucasus. The majority of Circassians in Israel are Muslims.

Balkar and Karachay nationalism is the national sentiment among the Balkars and Karachai. It generally manifests itself in:

Circassians in Turkey refers to people born in or residing in Turkey who are of Circassian origin. The Circassians are one of the largest ethnic minorities in Turkey, with a population estimated to be two million, or according to the EU reports, three. The term "Circassian" was formerly used in the Ottoman Empire in the late 1800s to refer to all North Caucasians.

The Natukhaj, Natuqwai or Natukhai are one of the twelve major Circassian tribes, representing one of the twelve stars on the green-and-gold Circassian flag. Their areas historically extended along the Black Sea coast from Anapa in the north to Tsemes Bay in the south and from the north side of the mountains to the lower Kuban River.

The Circassian diaspora refers to ethnic Circassian people around the world who live outside their homeland Circassia. Majority of the Circassians live in the diaspora, and their ancestors were settled during the resettlement of the Circassian population, especially during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. From 1763 to 1864, the Circassians fought against the Russian Empire in the Russian-Circassian War, finally succumbing to a scorched-earth genocide campaign initiated between 1862-1864. Afterwards, large numbers of Circassians were exiled and deported to the Ottoman Empire and other nearby regions; others were resettled in Russia far from their home territories. Circassians live in more than fifty countries, besides the Republic of Adygea. Total population estimates differ: according to some sources, some two million live in Turkey, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq; other sources have between one and four million in Turkey alone.

During the decline and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, Muslim inhabitants living in territories previously under Ottoman control, often found themselves as a persecuted minority after borders were re-drawn. These populations, who enjoyed the status of a privileged minority under Ottoman hegemony, were subject to expropriation, massacres, and even ethnic cleansing.

Late Ottoman genocides is a historiographical theory which sees the concurrent Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian genocides that occurred during the 1910–1920s as part of a single event rather than separate policies led by the Young Turks. Although some sources, including The Thirty-Year Genocide by the historians Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi, characterize this event as a genocide of Christians, others such as those written by the historians Dominik J. Schaller and Jürgen Zimmerer contend that such an approach "ignores the Young Turks' massive violence against non-Christians", in particular against Muslim Kurds.

Grigory Khristoforovich von Zass was a Russian Imperial cavalry general who commanded Russian cavalry troops in the Napoleonic Wars and Russo-Circassian War, initially gaining prominence for his genocidal actions against the Circassians, whom he reportedly saw as a "lowly race". He was the founder of Armavir.

Circassian Americans are Americans of ethnic Circassian origin. The term "Circassian Americans" can refer to ethnic Circassian immigrants to the United States, as well as their American-born descendants. The majority trace their roots to Circassians in Syria and Circassians in Turkey, however, there are also those who descend from Circassians in Jordan and other areas of the Circassian diaspora. They mostly live in Upstate New York, California, and New Jersey and number around 25,000. There is also a Circassian community in Canada.

The Circassian Union and Charity Society or Çerkes İttihat ve Teavün Cemiyeti was a Circassian nationalist charitable organization in the Ottoman Empire. It was based on several principles, mainly intellectualism, Circassian nationalism, and belief in Islam.