During the early years of World War II, Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated from their homes on the West Coast because military leaders and public opinion combined to fan unproven fears of sabotage. As the war progressed, many of the young Nisei, Japanese immigrants' children who were born with American citizenship, volunteered or were drafted to serve in the United States military. Japanese Americans served in all the branches of the United States Armed Forces, including the United States Merchant Marine. An estimated 33,000 Japanese Americans served in the U.S. military during World War II, of which 20,000 joined the Army. Approximately 800 were killed in action.

Sansei is a Japanese and North American English term used in parts of the world to refer to the children of children born to ethnically Japanese emigrants (Issei) in a new country of residence, outside of Japan. The nisei are considered the second generation, while grandchildren of the Japanese-born emigrants are called Sansei. The fourth generation is referred to as yonsei. The children of at least one nisei parent are called Sansei; they are usually the first generation of whom a high percentage are mixed-race, given that their parents were (usually), themselves, born and raised in America.

Japantown, commonly known as J Town, is a historic cultural district of San Jose, California, north of Downtown San Jose. Historically a center for San Jose's Japanese American and Chinese American communities, San Jose's Japantown is one of only three Japantowns that still exist in the United States, alongside San Francisco's Japantown and Los Angeles's Little Tokyo.

Japantown (日本人街) is a common name for Japanese communities in cities and towns outside Japan. Alternatively, a Japantown may be called J-town, Little Tokyo or Nihonmachi (日本町), the first two being common names for Japantown, San Francisco, Japantown, San Jose and Little Tokyo, Los Angeles.

Little Tokyo, also known as Little Tokyo Historic District, is an ethnically Japanese American district in downtown Los Angeles and the heart of the largest Japanese-American population in North America. It is the largest and most populous of only three official Japantowns in the United States, all of which are in California. Founded around the beginning of the 20th century, the area, sometimes called Lil' Tokyo, J-Town, Shō-Tōkyō (小東京), is the cultural center for Japanese Americans in Southern California. It was declared a National Historic Landmark District in 1995.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), formally the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, is a patriotic organization of U.S. war veterans who fought in wars, campaigns, and expeditions on foreign land, waters, or airspace as military service members. Established on September 29, 1899, in Columbus, Ohio, the VFW is headquartered in Kansas City, Missouri. It was congressionally chartered in 1936.

The Japanese American Citizens League is an Asian American civil rights charity, headquartered in San Francisco, with regional chapters across the United States.

The 442nd Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment of the United States Army. The regiment including the 100th Infantry Battalion is best known as the most decorated in U.S. military history, and as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-generation American soldiers of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who fought in World War II. Beginning in 1944, the regiment fought primarily in the European Theatre, in particular Italy, southern France, and Germany. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) was organized on March 23, 1943, in response to the War Department's call for volunteers to form the segregated Japanese American army combat unit. More than 12,000 Nisei volunteers answered the call. Ultimately 2,686 from Hawaii and 1,500 from mainland U.S. internment camps assembled at Camp Shelby, Mississippi in April 1943 for a year of infantry training. Many of the soldiers from the continental U.S. had families in internment camps while they fought abroad. The unit's motto was "Go for Broke".

Mike Masaru Masaoka was a Japanese-American lobbyist, author, and spokesman. He worked with the Japanese American Citizens League for over 30 years. He was a key player in encouraging cooperation of the JACL with Japanese American internment during World War II, but also fought for rights of Japanese-Americans during and after the war.

The Go for Broke Monument in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, California, commemorates Japanese Americans who served in the United States Army during World War II. It was created by Los Angeles architect Roger M. Yanagita whose winning design was selected over 138 other submissions from around the world.

The Grateful Crane Ensemble is a non-profit 501(c)(3) Asian American theatre company based in Southern California, established in July 2001.

The Capitol Mall or Capitol Mall Boulevard is a major street and landscaped parkway in the state capital city of Sacramento, California. Formerly known as M Street, it connects the city of West Sacramento in Yolo County to Downtown Sacramento. Capitol Mall begins at the eastern approach to the Tower Bridge, and runs east to 10th Street and the California State Capitol.

The Military Intelligence Service was a World War II U.S. military unit consisting of two branches, the Japanese American unit and the German-Austrian unit based at Camp Ritchie, best known as the "Ritchie Boys". The unit described here was primarily composed of Nisei who were trained as linguists. Graduates of the MIS language school (MISLS) were attached to other military units to provide translation, interpretation, and interrogation services.

Nisei is a Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants. The Nisei are considered the second generation and the grandchildren of the Japanese-born immigrants are called Sansei, or third generation. Though nisei means "second-generation immigrant", it often refers to the children of the initial diaspora, occurring in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and overlapping with the G.I. and silent generations.

Pierre Moulin was a French historian author, specializing in World War II, Nisei Japanese Americans, the Holocaust as well as Hawaiian history.

James Yutaka Matsumoto Omura was the English language editor of the Rocky Shimpo newspaper in Denver, Colorado, during World War II. He was an outspoken critic of the expulsion of people of Japanese ancestry from the west coast of the United States to concentration camps, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Subsequently, he became a vocal champion of the Nisei draft resisters, providing a 'substantial anchor' to the work of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee by publishing their grievances in the Rocky Shimpo. At a time when the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) preached passive conformity with the federal government as the best policy, Omura became the JACL's arch-enemy for counseling active resistance.

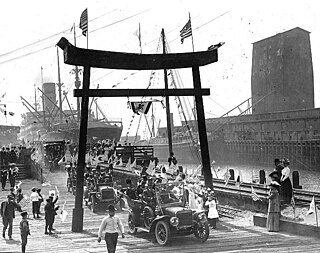

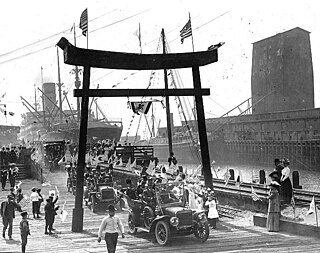

There is a population of Japanese Americans and Japanese expatriates in Greater Seattle, whose origins date back to the second half of the 19th century. Prior to World War II, Seattle's Japanese community had grown to become the second largest Nihonmachi on the West Coast of North America.

The Walnut Grove Japanese-American Historic District is a 5-acre (2.0 ha) designated U.S. Historic District in Walnut Grove, California. The bulk of Walnut Grove's Japantown was built in 1915–16 following the 1915 fire which destroyed Walnut Grove's Chinatown. Japantown was depopulated during the forced incarceration of Japanese and Japanese-Americans following the issuance of Executive Order 9066 in 1942, and was re-filled by Filipino and Mexican laborers, who took over work in local orchards and farms during the war. Although the original residents returned to Walnut Grove following the end of World War II, most left within a few years, and the district, with some exceptions, to this day retains the original architecture and style dating back to the 1916 reconstruction.

The history of Japanese-Americans and members of the Japanese diaspora community, known as Nikkei (日系), in the greater Portland, Oregon area dates back to the early 19th century. Large scale immigration began in the 1890s with the growth of the logging and railroad industries in the Pacific Northwest, after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 limited migration of new cheap labor from China and those other areas controlled by the Qing dynasty.

The Nihon Shōgakkō fire, or Japanese mission school fire, was a racially motivated arson that killed ten children in Sacramento, California, on April 15, 1923, at the dormitory of a Buddhist boarding school for students of Japanese ancestry. Fortunato Valencia Padilla, a Mexican-American itinerant from the Rio Grande Valley, admitted to committing the arson after his arrest in July 1923. Padilla confessed to at least 25 other fires in California, 13 of which were committed against Japanese households and Japanese-owned properties. Padilla was indicted on first-degree murder charges for the school fire on September 1, 1923, in Sacramento, with the prosecution seeking capital punishment. He was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was incarcerated at Folsom State Prison and later San Quentin State Prison; he died in 1970.