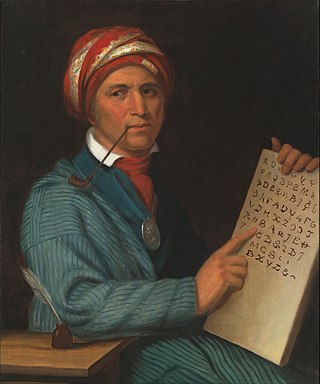

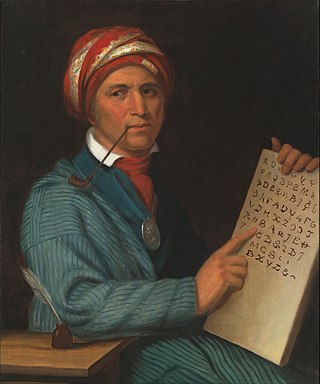

The Cherokee people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, edges of western South Carolina, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama consisting of around 40,000 square miles.

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as an independent nation-state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by the United States government in the early federal period of the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminoles. White Americans classified them as "civilized" because they had adopted attributes of the Anglo-American culture.

Conventionally, the descriptor 'civilized' is seldom utilized nowadays due to its derogatory nature, and the historical usage of the term as an obscuration for cultural imperialism. Therewith, the grouping of these aforementioned nations is referred to as The Five Tribes or simply Five Tribes.

The Lumbee are a Native American people primarily centered in Robeson, Hoke, Cumberland, and Scotland counties in North Carolina.

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws are laws in the United States that define Native American status by fractions of Native American ancestry. These laws were enacted by the federal government and state governments as a way to establish legally defined racial population groups. By contrast, many tribes do not include blood quantum as part of their own enrollment criteria. Blood quantum laws were first imposed by white settlers in the 18th century. Blood Quantum (BQ) is a very controversial topic.

The Houma are a historic Native American people of Louisiana on the east side of the Red River of the South. Their descendants, the Houma people or the United Houma Nation, have been recognized by the state as a tribe since 1972, but are not recognized by the federal government.

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe of Cherokee Native Americans headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. According to the UKB website, its members are mostly descendants of "Old Settlers" or "Western Cherokees," those Cherokees who migrated from the Southeast to present-day Arkansas and Oklahoma around 1817. Some reports estimate that Old Settlers began migrating west by 1800, before the forced relocation of Cherokees by the United States in the late 1830s under the Indian Removal Act.

State-recognized tribes in the United States are organizations that identify as Native American tribes or heritage groups that do not meet the criteria for federally recognized Indian tribes but have been recognized by a process established under assorted state government laws for varying purposes or by governor's executive orders. State recognition does not dictate whether or not they are recognized as Native American tribes by continually existing tribal nations.

The United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation, also called the Shawnee Nation, United Remnant Band (URB), is an organization that self-identifies as a Native American tribe in Ohio. Its members identify as descendants of Shawnee people. In 2016, the organization incorporated as a church.

The Cherokee Nation, formerly known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three federally recognized tribes of Cherokees in the United States. It includes people descended from members of the Old Cherokee Nation who relocated, due to increasing pressure, from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokees who were forced to relocate on the Trail of Tears. The tribe also includes descendants of Cherokee Freedmen, Absentee Shawnee, and Natchez Nation. As of 2023, over 450,000 people were enrolled in the Cherokee Nation.

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the Indigenous peoples whose tribal nations historically or currently are based in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States of America.

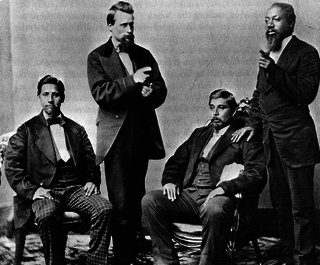

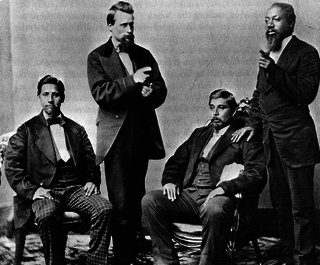

The Cherokee Freedmen controversy was a political and tribal dispute between the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen regarding the issue of tribal membership. The controversy had resulted in several legal proceedings between the two parties from the late 20th century to August 2017.

Cherokee heritage groups are associations, societies and other organizations located primarily in the United States. Such groups consist of persons who do not qualify for enrollment in any of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes. As the Cherokee Nation enrolls all people who can prove descent from a Cherokee ancestor, many of these groups consist of those who claim Cherokee ancestry but have no documentation to prove this alleged heritage. Some have had their claims of ancestry checked and proven to be false. A total of 819,105 Americans claimed Cherokee heritage in the 2010 Census, more than any other named tribe in the Census.

Native American identity in the United States is a community identity, determined by the tribal nation the individual or group belongs to. While it is common for non-Natives to consider it a racial or ethnic identity, for Native Americans in the United States it is considered to be a political identity, based on citizenship and immediate family relationships. As culture can vary widely between the 574 extant federally recognized tribes in the United States, the idea of a single unified "Native American" racial identity is a European construct that does not have an equivalent in tribal thought.

Native American recognition in the United States, for tribes, usually means being recognized by the United States federal government as a community of Indigenous people that has been in continual existence since prior to European contact, and which has a sovereign, government-to-government relationship with the Federal government of the United States. In the United States, the Native American tribe is a fundamental unit of sovereign tribal government. This recognition comes with various rights and responsibilities. The United States recognizes the right of these tribes to self-government and supports their tribal sovereignty and self-determination. These tribes possess the right to establish the legal requirements for membership. They may form their own government, enforce laws, tax, license and regulate activities, zone, and exclude people from tribal territories. Limitations on tribal powers of self-government include the same limitations applicable to states; for example, neither tribes nor states have the power to make war, engage in foreign relations, or coin money.

The Yowani were a historical group of Choctaw people who lived in Texas. Yowani was also the name of a preremoval Choctaw village.

The Delaware Tribe of Indians, formerly known as the Cherokee Delaware or the Eastern Delaware, based in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, is one of three federally recognized tribes of the Lenape people in the United States. The others are the Delaware Nation based in Anadarko, Oklahoma, and the Stockbridge-Munsee Community of Wisconsin. More Lenape or Delaware people live in Canada.

The Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama is a state-recognized tribe in Alabama and Cherokee heritage group. It is based in northern Alabama and gained state-recognition under the Davis-Strong Act in 1984.

Cherokee descent, "being of Cherokee descent", or "being a Cherokee descendant" are all terms for individuals with some degree of documented Cherokee ancestry but do not meet the criteria for tribal citizenship. The terms are also used by non-Native individuals who self-identify as Cherokee despite lacking documentation or community recognition.