The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated codex hand-written in an unknown, possibly meaningless writing system. The manuscript is named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish book dealer who purchased it in 1912. The vellum on which it is written has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century (1404–1438), and the text may have been composed in Italy during the Italian Renaissance. However, its origins and authorship are not unambiguously known, and remain the subject of study and speculation. Some of the pages are missing, with around 240 remaining. The text is written from left to right, and most of the pages have illustrations or diagrams. Some pages are foldable sheets of varying sizes.

Khitan or Kitan, also known as Liao, is a now-extinct language once spoken in northeast Asia by the Khitan people. It was the official language of the Liao Empire (907–1125) and the Qara Khitai (1124–1218).

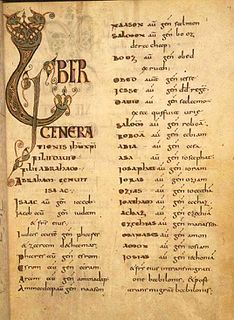

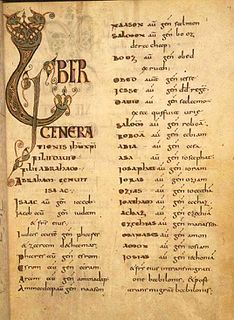

British Library, Harley MS 1775 is an illuminated Gospel Book produced in Italy during the last quarter of the 6th century. The text is in Latin and is a mixture of the Vulgate and Old Latin translations. This text is called "source Z" in critical studies of the Latin New Testament.

The Codex Beneventanus is an 8th-century illuminated codex containing a Gospel Book. According to a subscription on folio 239 verso, the manuscript was written by a monk named Lupus for one Ato, who was probably Ato, abbot (736–760) of the monastery of San Vincenzo al Volturno, near Benevento. The unusual odd number of Canon Tables suggests these seven folios were prepared as much as two centuries earlier than the rest of the codex.

British Library, Royal MS 1. B. VII is an 8th-century Anglo-Saxon illuminated Gospel Book. It is closely related to the Lindisfarne Gospels, being either copied from it or from a common model. It is not as lavishly illuminated, and the decoration shows Merovingian influence. The manuscript contains the four Gospels in the Latin Vulgate translation, along with prefatory and explanatory matter. It was presented to Christ Church, Canterbury in the 920s by King Athelstan, who had recorded in a note in Old English (f.15v) that upon his accession to the throne in 925 he had freed one Eadelm and his family from slavery, the earliest recorded manumission in (post-Roman) England.

The Schuttern Gospels is an early 9th century illuminated Gospel Book that was produced at Schuttern Abbey in Baden. According to a colophon on folio 206v, the manuscript was written by the deacon Liutharius, at the order of his abbot, Bertricus.

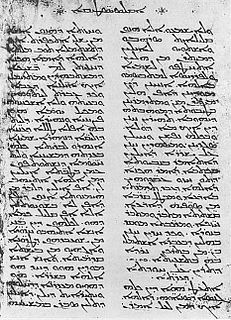

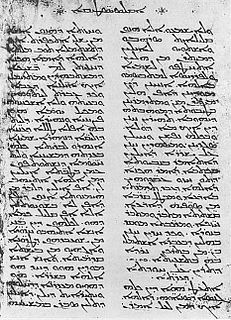

The Khitan large script was one of two writing systems used for the now-extinct Khitan language. It was used during the 10th–12th centuries by the Khitan people, who had created the Liao Empire in north-eastern China. In addition to the large script, the Khitans simultaneously also used a functionally independent writing system known as the Khitan small script. Both Khitan scripts continued to be in use to some extent by the Jurchens for several decades after the fall of the Liao Dynasty, until the Jurchens fully switched to a script of their own. Examples of the scripts appeared most often on epitaphs and monuments, although other fragments sometimes surface.

An undeciphered writing system is a written form of language that is not currently understood.

Jurchen script was the writing system used to write the Jurchen language, the language of the Jurchen people who created the Jin Empire in northeastern China in the 12th–13th centuries. It was derived from the Khitan script, which in turn was derived from Chinese. The script has only been decoded to a small extent.

The Khitan small script was one of two writing systems used for the now-extinct Khitan language. It was used during the 10th–12th century by the Khitan people, who had created the Liao Empire in present-day northeastern China. In addition to the small script, the Khitans simultaneously also used a functionally independent writing system known as the Khitan large script. Both Khitan scripts continued to be in use to some extent by the Jurchens for several decades after the fall of the Liao Dynasty, until the Jurchens fully switched to a script of their own. Examples of the scripts appeared most often on epitaphs and monuments, although other fragments sometimes surface.

National Library of Russia, Codex Syriac 1, designated by siglum A, is a manuscript of Syriac version of the Eusebian Ecclesiastical History. It is dated by a Colophon to the year 462. The manuscript is lacunose.

Jin Guangping or Aisin-Gioro Hengxu (1899–1966) was a Chinese linguist of Manchu ethnicity who is known for his studies of the Jurchen and Khitan languages and scripts.

The Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM) of the Russian Academy of Sciences, formerly the St. Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, is a research institute in Saint Petersburg, Russia that houses various collections of manuscripts and early printed material in Asian languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan, and Tangut.

The Birmingham Quran manuscript is a parchment on which two leaves of an early Quranic manuscript are written. In 2015 the manuscript, which is held by the University of Birmingham, was radiocarbon dated to between 568 and 645 CE. It is part of the Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern manuscripts, held by the university's Cadbury Research Library.

In Muslim tradition the Quran is a final revelation from God, Islam’s divine text, delivered to the Prophet of Islam Muhammad, through the angel Jibril (Gabriel). Muhammad’s revelations were said to have been recorded orally and in writing, through Muhammad and his followers up until his death in 632, and then compiled by first caliph Abu Bakr and codified during the reign of the third caliph Uthman so that the standard codex edition of the Quran or "Muṣḥaf" was completed around 650 CE, according to Muslim scholars. However, some Western scholars have questioned this, suggesting the Quran was canonized at a later date, based on the fact that the classical Islamic narratives were written generations—150 to 200 years—after the death of Muhammad.

Irina Fedorovna Popova is a Russian sinologist and historian. Since April 2003 she has been the Director of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences at Saint Petersburg, Russia. She is also Head of the Department of Manuscripts and Documents of the IOM RAS, and Full Professor at St Petersburg State University.

The Liao dynasty was a Khitan-led dynasty of China that ruled over parts of Northern China, Manchuria, the Mongolian Plateau, northern Korean Peninsula, and what is modern-day Russian Far East from 916 until 1125 when it was conquered by the Jin dynasty. Remnants of the Liao court fled westward and created the Western Liao dynasty which in turn was annexed by the Mongol Empire in 1218.

Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus, designated by Vp, is an old Masoretic manuscript of Hebrew Bible, especially the Latter Prophets. This codex contains the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Minor Prophets, with both the small and the large Masora.

![Top line: Khitan text meaning "Great Central [?] Khitan State"

Bottom line: Corresponding Chinese translation (Da Zhong Yang ##Qi Dan Guo ) Khitan manuscript text A.png](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f7/Khitan_manuscript_text_A.png)