The First Chechen War, also referred to as the First Russo-Chechen War, was a struggle for independence waged by the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria against the Russian Federation from December 11th, 1994 to August 31st, 1996. This conflict was preceded by the battle of Grozny in November 1994, during which Russia covertly sought to overthrow the new Chechen government. Following the intense Battle of Grozny in 1994–1995, which concluded as a pyrrhic victory for the Russian federal forces, their subsequent efforts to establish control over the remaining lowlands and mountainous regions of Chechnya were met with fierce resistance from Chechen guerrillas who often conducted surprise raids.

The Second Chechen War took place in Chechnya and the border regions of the North Caucasus between the Russian Federation and the breakaway Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, from August 1999 to April 2009.

OMON is a system of special police units within the National Guard of Russia. It previously operated within the structures of the Soviet and Russian Ministries of Internal Affairs (MVD). Originating as the special forces unit of the Soviet Militsiya in 1988, it has played major roles in several armed conflicts during and following the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Vladimir Anatolievich Shamanov is a retired Colonel General of the Russian Armed Forces who was Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Airborne Troops (VDV) from May 2009 to October 2016 and a Russian politician. After his retirement in October 2016, Shamanov became head of the State Duma Defense Committee.

The Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, known simply as Ichkeria, and also known as Chechnya, was a de facto state that controlled most of the former Checheno-Ingush ASSR.

The 1999–2000 battle of Grozny was the siege and assault of the Chechen capital Grozny by Russian forces, lasting from late 1999 to early 2000. This siege and assault of the Chechen capital resulted in the widespread devastation of Grozny. In 2003, the United Nations designated Grozny as the most destroyed city on Earth due to the extensive damage it suffered. The battle had a devastating impact on the civilian population. It is estimated that between 5,000 and 8,000 civilians were killed during the siege, making it the bloodiest episode of the Second Chechen War.

In Chechnya, mass graves containing hundreds of corpses have been uncovered since the beginning of the Chechen wars in 1994. As of June 2008, there were 57 registered locations of mass graves in Chechnya. According to Amnesty International, thousands may be buried in unmarked graves including up to 5,000 civilians who disappeared since the beginning of the Second Chechen War in 1999. In 2008, the largest mass grave found to date was uncovered in Grozny, containing some 800 bodies from the First Chechen War in 1995. Russia's general policy to the Chechen mass graves is to not exhume them.

Human rights violations were committed by the warring sides during the second war in Chechnya. Both Russian officials and Chechen rebels have been regularly and repeatedly accused of committing war crimes including kidnapping, torture, murder, hostage taking, looting, rape, decapitation, and assorted other breaches of the law of war. International and humanitarian organizations, including the Council of Europe and Amnesty International, have criticized both sides of the conflict for blatant and sustained violations of international humanitarian law.

Russia incurred much international criticism for its conduct during the Second Chechen War, which started in 1999. The governments of the United States and other countries condemned deaths and expulsions among civilians. The United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNHCR) passed two resolutions in 2000 and 2001 condemning human rights violations in Chechnya and requiring Russia to set up an independent national commission of inquiry to investigate the matter. However, a third resolution on these lines failed in 2004. The Council of Europe in multiple resolutions and statements between 2003 and 2007 called on Russia to cease human rights violations. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) between 2005 and 2007 conducted legal cases brought by Chechens against the Russian government, and in many of these cases held Russia responsible for deaths, disappearances and torture.

The Battle of Grozny of August 1996, also known as Operation Jihad or Operation Zero Option, when Chechen fighters regained and then kept control of Chechnya's capital Grozny in a surprise raid. The Russian Federation had conquered the city in a previous battle for Grozny that ended in February 1995 and subsequently posted a large garrison of federal and republican Ministry of the Interior (MVD) troops in the city.

The Grozny OMON friendly fire incident took place on March 2, 2000, when an OMON unit from Podolsk, supported by paramilitary police from the Sverdlovsk Oblast in armored vehicles, opened friendly fire on a motorized column of OMON from Sergiyev Posad, which had just arrived in Chechnya to replace them.

The Alkhan-Yurt massacre was the December 1999 incident in the village of Alkhan-Yurt near the Chechen capital Grozny involving Russian troops under command of General Vladimir Shamanov. The villagers claimed that approximately 41 civilians were killed in the spree, while human rights groups confirmed and documented 17 incidents of murder and three incidents of rape.

The Staropromyslovsky massacre occurred between December 1999 and January 2000 when at least 38 confirmed civilians were summarily executed by Russian federal soldiers during an apparent spree in Staropromyslovsky City District of Grozny, the capital of the Chechen Republic, according to survivors and eyewitnesses. The killings went unpunished and publicly unacknowledged by the Russian authorities. In 2007, one case of a triple murder was ruled against Russia in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

The Samashki massacre was the mass murder of Chechen civilians by Russian Forces in April 1995 during the First Chechen War. Hundreds of Chechen civilians died as result of a Russian cleansing operation and the bombardment of the village. Most of the victims were shot in cold blood at close range or killed by grenades thrown into basements where they were hiding. Others were burned alive or were shot while trying to escape their burning houses. Much of the village was destroyed and the local school blown up by Russian forces as they withdrew. The incident attracted wide attention in Russia and abroad.

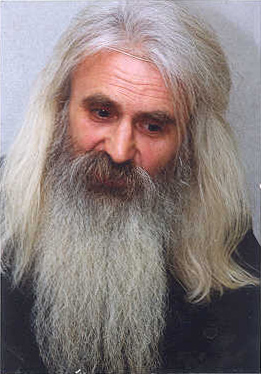

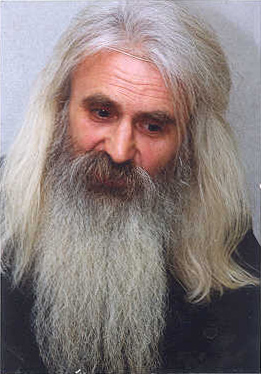

Viktor Alekseyevich Popkov was a Russian dissident, Christian, humanitarian, human rights activist and journalist.

Sergei Babin is a former Russian police officer who had served in the OMON detachment sent from Saint Petersburg and is an accused war criminal.

Estamirov and Others v. Russia was a European Court of Human Rights ruling in the case of the February 5, 2000, Novye Aldi massacre in Chechnya, which unanimously held Russia responsible for violations of Articles 2 and 13 of the European Convention of Human Rights. The case was brought to the European Court by several members of the Estamirov family together with the British solicitor Gareth Peirce and the organization Russian Justice Initiative.

Musayev, Labazanova and Magomadov v. Russia was the July 26, 2007, ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in the case of the February 2000 Novye Aldi massacre in Chechnya, which unanimously held Russia responsible for violations of Articles 2 and 13 of the European Convention of Human Rights. The three applications, which the Court joined into one case, concerned the murders of 11 civilian persons committed during a rampage in the Chechen capital Grozny by the Russian OMON special police unit.

Zachistka is a Russian military term for "mopping-up" operations to cleanse a territory from enemy military forces or civilians. They were frequently conducted in villages and included house to house searches. The term was widely used in the Second Chechen War. A number of zachistka operations became notorious for human rights violations by Russian forces, including ethnic cleansing and pillaging, and the term zachistka is used in English exclusively to refer to these violations, particularly in Chechnya and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Russian war crimes are violations of international criminal law including war crimes, crimes against humanity and the crime of genocide which the official armed and paramilitary forces of Russia have been accused of committing since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. These accusations have also been extended to the aiding and abetting of crimes which have been committed by proto-statelets or puppet statelets which are armed and financed by Russia, including the Luhansk People's Republic and the Donetsk People's Republic. These war crimes have included murder, torture, terrorism, deportation and forced transfer, abduction, rape, looting, unlawful confinement, unlawful airstrikes and attacks against civilian objects, used of banned chemical weapons, and wanton destruction.