Prewar

The Code and Signal Section was formally made a part of the Division of Naval Communications (DNC), as Op-20-G, on July 1, 1922. In January 1924, a 34-year-old U.S. Navy lieutenant named Laurance F. Safford was assigned to expand OP-20-G's domain to radio interception. He worked out of Room 2646, on the top floor of the Navy Department building in Washington, D.C.

Japan was of course a prime target for radio interception and cryptanalysis, but there was the problem of finding personnel who could speak Japanese. The Navy had a number of officers who had served in a diplomatic capacity in Japan and could speak Japanese fluently, but there was a shortage of radiotelegraph operators who could read Japanese Wabun code communications sent in kana . Fortunately, a number of US Navy and Marine radiotelegraph operators operating in the Pacific had formed an informal group in 1923 to compare notes on Japanese kana transmissions. Four of these men became instructors in the art of reading kana transmissions when the Navy began conducting classes in the subject in 1928.

The classes were conducted by the Room 2426 crew, and the radiotelegraph operators became known as the "On-The-Roof Gang". By June 1940, OP-20-G included 147 officers, enlisted men, and civilians, linked into a network of radio listening posts as far-flung as the Army's.

OP-20-G did some work on Japanese diplomatic codes, but the organization's primary focus was on Japanese military codes. The US Navy first got a handle on Japanese naval codes in 1922, when Navy agents broke into the Japanese consulate in New York City, cracked the safe, took photographs of pages of a Japanese navy codebook, and left, having put everything back as they had found it.

Before the war, the Navy cipher bureau operated out of three main bases:

- Station NEGAT at headquarters in Washington, D.C.

- Station HYPO (or FRUPAC), a section at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii

- Station CAST, a section in the fortified caves of the island of Corregidor, in the Philippines, with codebreakers and a network of listening and radio direction finding stations.

- FRUMEL was established in Melbourne when Navy signals intelligence personnel from the Philippines were evacuated to Australia. Evacuated Army signals intelligence personnel went to the Central Bureau.

The US Army Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) and OP-20-G were hobbled by bureaucracy and rivalry, competing with each other to provide their intelligence data, codenamed "MAGIC", to high officials. Complicating matters was that the Coast Guard, the FBI, and even the FCC also had radio-intercept operations.

The Navy organization at OP-20-G was more conventionally hierarchical than the Army at Arlington Hall which went more on merit rather than rank (like Bletchley Park), though commissions were handed out to "civilians in uniform" with rank according to age (an ensign for 28 or under, a lieutenant to 35 or a lieutenant commander if over 35). But control was by "regular military types". The Navy wanted the Army to forbid civilians to touch the SIGABA cipher machine like the Navy; though it was developed by a civilian (William Friedman). A Royal Navy visitor and intercept specialist Commander Sandwith reported in 1942 on "the dislike of Jews prevalent in the US Navy (while) nearly all the leading Army cryptographers are Jews".

In 1940, SIS and OP-20-G came to agreement with guide lines for handling MAGIC; the Army was responsible on even-numbered days and the Navy on odd-numbered days. So, on the first minute after midnight on 6 December 1941 the Navy took over. But USN Lt-Comdr Alwin Kramer had no relief officer (unlike the Army, with Dusenbury and Bratton); and that night was being driven around by his wife. He was also responsible for distributing MAGIC information to the President; in January 1941 the Army agreed that they would supply the White House in January, March, May, July, September and November and the Navy in February, April, June, August, October and December. But in May 1941 MAGIC documents were found in the desk of Roosevelt's military aide Edwin "Pa" Watson and the Navy took over; while the Army provided MAGIC to the State Department instead.

The result was that much of the MAGIC was delayed or unused. There was no efficient process for assessing and organizing the intelligence, as was provided postwar by a single intelligence agency.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

In the early hours of the morning of 7 December 1941, the U.S. Navy communications intercept station at Fort Ward on Bainbridge Island, Washington, picked up a radio message being sent by the Japanese government to the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C. It was the last in a series of 14 messages that had been sent over the previous 18 hours.

The messages were decrypted by a PURPLE analogue machine at OP-20-G and passed to the SIS for translation from Japanese, early on the morning of December 7. Army Colonel Rufus S. Bratton and Navy Lieutenant Commander Alwin Kramer independently inspected the decrypts.

The decrypts instructed the Japanese ambassador to Washington to inform the US Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, at 1:00 PM Washington time that negotiations between the United States and Japan were ended. The embassy was then to destroy their cipher machines. This sounded like war, and although the message said nothing about any specific military action, Kramer also realized that the sun would be rising over the expanses of the central and western Pacific by that time. The two men both tried to get in touch with Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall.

After some agonizing delays, Marshall got the decrypts and methodically examined them. He realized their importance and sent a warning to field commanders, including Major General Walter Short, the Army commander in Hawaii. However, Marshall was reluctant to use the telephone because he knew that telephone scramblers weren't very secure and sent it by less direct channels. Due to various constraints and bumblings, Short got the message many hours after the Japanese bombs had smashed the US Navy's fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor.

Ultra was the designation adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. Ultra eventually became the standard designation among the western Allies for all such intelligence. The name arose because the intelligence obtained was considered more important than that designated by the highest British security classification then used and so was regarded as being Ultra Secret. Several other cryptonyms had been used for such intelligence.

Arlington Hall is a historic building in Arlington, Virginia, originally a girls' school and later the headquarters of the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) cryptography effort during World War II. The site presently houses the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center, and the Army National Guard's Herbert R. Temple, Jr. Readiness Center. It is located on Arlington Boulevard between S. Glebe Road and S. George Mason Drive.

Captain, U.S.N. Laurance Frye Safford was a U.S. Navy cryptologist. He established the Naval cryptologic organization after World War I, and headed the effort more or less constantly until shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His identification with the Naval effort was so close that he was the Friedman of the Navy.

Joseph John Rochefort was an American naval officer and cryptanalyst. He was a major figure in the United States Navy's cryptographic and intelligence operations from 1925 to 1946, particularly in the Battle of Midway. His contributions and those of his team were pivotal to victory in the Pacific War.

Magic was an Allied cryptanalysis project during World War II. It involved the United States Army's Signals Intelligence Service (SIS) and the United States Navy's Communication Special Unit.

The bombe was an electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II. The US Navy and US Army later produced their own machines to the same functional specification, albeit engineered differently both from each other and from Polish and British bombes.

Cryptography was used extensively during World War II because of the importance of radio communication and the ease of radio interception. The nations involved fielded a plethora of code and cipher systems, many of the latter using rotor machines. As a result, the theoretical and practical aspects of cryptanalysis, or codebreaking, were much advanced.

Various conspiracy theories allege that U.S. government officials had advance knowledge of Japan's December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. Ever since the Japanese attack, there has been debate as to why and how the United States was caught off guard, and how much and when American officials knew of Japanese plans for an attack. In September 1944, John T. Flynn, a co-founder of the non-interventionist America First Committee, launched a Pearl Harbor counter-narrative when he published a 46-page booklet entitled The Truth about Pearl Harbor, arguing that Roosevelt and his inner circle had been plotting to provoke the Japanese into an attack on the U.S. and thus provide a reason to enter the war since January 1941.

The Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) was the United States Army codebreaking division through World War II. It was founded in 1930 to compile codes for the Army. It was renamed the Signal Security Agency in 1943, and in September 1945, became the Army Security Agency. For most of the war it was headquartered at Arlington Hall, on Arlington Boulevard in Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington (D.C.). During World War II, it became known as the Army Security Agency, and its resources were reassigned to the newly established National Security Agency (NSA).

Station HYPO, also known as Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC), was the United States Navy signals monitoring and cryptographic intelligence unit in Hawaii during World War II. It was one of two major Allied signals intelligence units, called Fleet Radio Units in the Pacific theaters, along with FRUMEL in Melbourne, Australia. The station took its initial name from the phonetic code at the time for "H" for Heʻeia, Hawaii radio tower. The precise importance and role of HYPO in penetrating the Japanese naval codes has been the subject of considerable controversy, reflecting internal tensions amongst US Navy cryptographic stations.

Station CAST was the United States Navy signals monitoring and cryptographic intelligence fleet radio unit at Cavite Navy Yard in the Philippines, until Cavite was captured by the Japanese forces in 1942, during World War II. It was an important part of the Allied intelligence effort, addressing Japanese communications as the War expanded from China into the rest of the Pacific theaters. As Japanese advances in the Philippines threatened CAST, its staff and services were progressively transferred to Corregidor in Manila Bay, and eventually to a newly formed US-Australian station, FRUMEL in Melbourne, Australia.

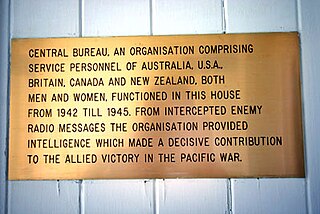

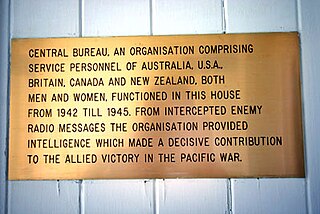

The Central Bureau was one of two Allied signals intelligence (SIGINT) organisations in the South West Pacific area (SWPA) during World War II. Central Bureau was attached to the headquarters of the Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur. The role of the Bureau was to research and decrypt intercepted Imperial Japanese Army traffic and work in close co-operation with other SIGINT centers in the United States, United Kingdom and India. Air activities included both army and navy air forces, as there was no independent Japanese air force.

With the rise of easily-intercepted wireless telegraphy, codes and ciphers were used extensively in World War I. The decoding by British Naval intelligence of the Zimmermann telegram helped bring the United States into the war.

Henry Christian Clausen was an American lawyer, and investigator. He authored the Clausen Report, an 800-page report on the Army Board's Pearl Harbor Investigation. He traveled over 55,000 miles over seven months in 1945, and interviewed nearly a hundred personnel, Army, Navy, British and civilian, as a Special Investigator for the Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson carrying out an investigation ordered by Congress.

Before the development of radar and other electronics techniques, signals intelligence (SIGINT) and communications intelligence (COMINT) were essentially synonymous. Sir Francis Walsingham ran a postal interception bureau with some cryptanalytic capability during the reign of Elizabeth I, but the technology was only slightly less advanced than men with shotguns, during World War I, who jammed pigeon post communications and intercepted the messages carried.

Fleet Radio Units (FRU) were the major centers for Allied cryptological and signals intelligence during the Pacific Campaign of World War II. Initially two FRUs were established in the Pacific, one at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, called Station HYPO or FRUPAC, and the other, called Station CAST or Belconnen, at Cavite Naval Yard, then Corregidor, Philippines. With the fall of the Philippines to Imperial Japanese forces in April and May 1942, CAST personnel were evacuated to a newly established FRU at Melbourne, Australia, called FRUMEL.

John "Jack" Roland Redman was an admiral in the United States Navy. A naval communications officer, he played key roles in signals intelligence during World War II in Washington, D.C., and on the staff of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. He also competed at the 1920 Summer Olympics.

Japanese army and diplomatic codes. This article is on Japanese army and diplomatic ciphers and codes used up to and during World War II, to supplement the article on Japanese naval codes. The diplomatic codes were significant militarily, particularly those from diplomats in Germany.

The United States Coast Guard Unit 387 became the official cryptanalytic unit of the Coast Guard collecting communications intelligence for Coast Guard, U.S. Department of Defense, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1931. Prior to becoming official, the Unit worked under the U.S. Treasury Department intercepting communications during the prohibition. The Unit was briefly absorbed into the U.S. Navy in 1941 during World War II (WWII) before returning to be a Coast Guard unit again following the war. The Unit contributed to significant success in deciphering rum runner codes during the prohibition and later Axis agent codes during WWII, leading to the breaking of several code systems including the Green and Red Enigma machines.

Virginia Dare Aderholdt was an Arlington Hall cryptanalyst and Japanese translator. She decrypted the intercepted Japanese surrender message at the close of World War II on August 14, 1945.