Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their descent from the guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 14th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities and clients. Modern Freemasonry broadly consists of two main recognition groups: Regular Freemasonry, which insists that a volume of scripture be open in a working lodge, that every member professes belief in a Supreme Being, that no women be admitted, and that the discussion of religion and politics do not take place within the lodge; and Continental Freemasonry, which consists of the jurisdictions that have removed some, or all, of these restrictions.

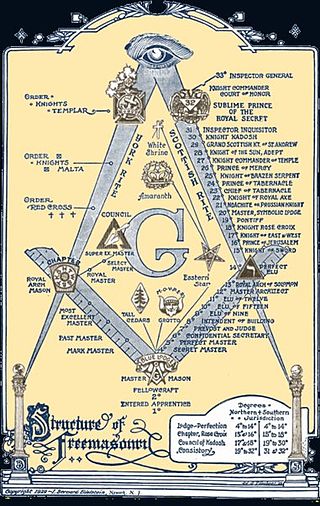

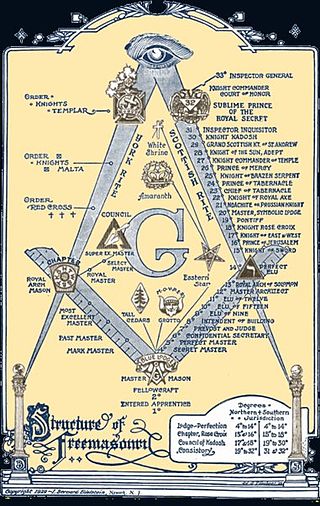

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered by a Grand Lodge, but is subject to its direction only in enforcing the published constitution of the jurisdiction. By exception the three surviving lodges that formed the world's first known grand lodge in London have the unique privilege to operate as time immemorial, i.e., without such warrant; only one other lodge operates without a warrant – the Grand Stewards' Lodge in London, although it is not also entitled to the "time immemorial" title. A Freemason is generally entitled to visit any lodge in any jurisdiction in amity with his own. In some jurisdictions this privilege is restricted to Master Masons. He is first usually required to check, and certify, the regularity of the relationship of the Lodge – and be able to satisfy that Lodge of his regularity of membership. Freemasons gather together as a Lodge to work the three basic Degrees of Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft, and Master Mason.

The history of Freemasonry encompasses the origins, evolution and defining events of the fraternal organisation known as Freemasonry. It covers three phases. Firstly, the emergence of organised lodges of operative masons during the Middle Ages, then the admission of lay members as "accepted" or "speculative" masons, and finally the evolution of purely speculative lodges, and the emergence of Grand Lodges to govern them. The watershed in this process is generally taken to be the formation of the first Grand Lodge in London in 1717. The two difficulties facing historians are the paucity of written material, even down to the 19th century, and the misinformation generated by masons and non-masons alike from the earliest years.

The relationship between Mormonism and Freemasonry began early in the life of Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement. Smith's older brother, Hyrum, and possibly his father, Joseph, Sr. were Freemasons while the family lived near Palmyra, New York. In the late 1820s, the western New York region was swept with anti-Masonic fervor.

Co-Freemasonry is a form of Freemasonry which admits both men and women. It began in France in the 1890s with the forming of Le Droit Humain, and is now an international movement represented by several Co-Freemasonic administrations throughout the world. Most male-only Masonic Lodges do not recognise Co-Freemasonry, holding it to be irregular.

There are many organisations and orders which form part of the widespread fraternity of Freemasonry, each having its own structure and terminology. Collectively these may be referred to as Masonic bodies, Masonic orders, Concordant bodies or appendant bodies of Freemasonry.

Masonic landmarks are a set of principles that many Freemasons claim to be ancient and unchangeable precepts of Masonry. Issues of the "regularity" of a Freemasonic Lodge, Grand Lodge or Grand Orient are judged in the context of the landmarks. Because each Grand Lodge is self-governing, with no single body exercising authority over the whole of Freemasonry, the interpretations of these principles can and do vary, leading to controversies of recognition. Different Masonic jurisdictions have different landmarks.

Freemasonry has had a complex relationship with women for centuries. A few women were involved in Freemasonry before the 18th century, despite de jure prohibitions in the Premier Grand Lodge of England.

There are a number of masonic manuscripts that are important in the study of the emergence of Freemasonry. Most numerous are the Old Charges or Constitutions. These documents outlined a "history" of masonry, tracing its origins to a biblical or classical root, followed by the regulations of the organisation, and the responsibilities of its different grades. More rare are old hand-written copies of ritual, affording a limited understanding of early masonic rites. All of those which pre-date the formation of Grand Lodges are found in Scotland and Ireland, and show such similarity that the Irish rituals are usually assumed to be of Scottish origin. The earliest Minutes of lodges formed before the first Grand Lodge are also located in Scotland. Early records of the first Grand Lodge in 1717 allow an elementary understanding of the immediate pre-Grand Lodge era and some insight into the personalities and events that shaped early-18th-century Freemasonry in Britain.

The organisation now known as the Premier Grand Lodge of England was founded on 24 June 1717 as the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster. Originally concerned with the practice of Freemasonry in London and Westminster, it soon became known as the Grand Lodge of England. Because it was the first Masonic Grand Lodge to be created, modern convention now calls it the Premier Grand Lodge of England in order to distinguish it from the Most Ancient and Honourable Society of Free and Accepted Masons according to the Old Constitutions, usually referred to as the Ancient Grand Lodge of England, and the Grand Lodge of All England Meeting at York. It existed until 1813, when it united with the Ancient Grand Lodge of England to create the United Grand Lodge of England.

The Royal Arch is a degree of Freemasonry. The Royal Arch is present in all main masonic systems, though in some it is worked as part of Craft ('mainstream') Freemasonry, and in others in an appendant ('additional') order. Royal Arch Masons meet as a Chapter; in the Supreme Order of the Royal Arch as practised in the British Isles, much of Europe and the Commonwealth, Chapters confer the single degree of Royal Arch Mason.

Tracing boards are painted or printed illustrations depicting the various emblems and symbols of Freemasonry. They can be used as teaching aids during the lectures that follow each of the Masonic Degrees, when an experienced member explains the various concepts of Freemasonry to new members. They can also be used by experienced members as reminders of the concepts they learned as they went through the ceremonies of the different masonic degrees.

Royal Arch Masonry is the first part of the American York Rite system of Masonic degrees. Royal Arch Masons meet as a Chapter, and the Royal Arch Chapter confers four degrees: Mark Master Mason, Past Master, Most Excellent Master, and Royal Arch Mason.

Masonic ritual is the scripted words and actions that are spoken or performed during the degree work in a Masonic lodge. Masonic symbolism is that which is used to illustrate the principles which Freemasonry espouses. Masonic ritual has appeared in a number of contexts within literature including in "The Man Who Would Be King", by Rudyard Kipling, and War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy.

The Grand Lodge of All EnglandMeeting since Time Immemorial in the City of York was a body of Freemasons which existed intermittently during the Eighteenth Century, mainly based in the City of York. It does not appear to have been a regulatory body in the usual manner of a masonic Grand Lodge, and as such is seen as a "Mother Lodge" like Kilwinning in Scotland. It met to create Freemasons, and as such enabled the foundation of new lodges. For much of its career, it was the only lodge in its own jurisdiction, but even with dependent lodges it continued to function mainly as an ordinary lodge of Freemasons. Having existed since at least 1705 as the Ancient Society of Freemasons in the City of York, it was in 1725, possibly in response to the expansion of the new Grand Lodge in London, that they styled themselves the Grand Lodge of All England Meeting at York. Activity ground to a halt some time in the 1730s, but was revived with renewed vigour in 1761.

In Freemasonry, a Mason at sight, or Mason on sight, is a non-Mason who has been initiated into Freemasonry and raised to the degree of Master Mason through a special application of the power of a Grand Master.

Clement Edwin Stretton was a consulting engineer and author. He wrote several books, as well as numerous papers on the subjects of railways and freemasonry, being active during the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries. His two major works, Safe Railway Working: A Treatise on Railway Accidents (1887) and The Locomotive Engine and its Development (1892), ran to 3 and 6 editions respectively. He also produced a lengthy history of the Midland Railway (1901).

Masonic myths occupy a central place in Freemasonry. Derived from founding texts or various biblical legends, they are present in all Masonic rites and ranks. Using conceptual parables, they can serve Freemasons as sources of knowledge and reflection, where history often vies with fiction. They revolve mainly around the legendary stories of the construction of Solomon's temple, the death of its architect Hiram, and chivalry. Some of the original mythical themes are still part, to a greater or lesser extent and explicitly, of the symbols that make up the corpus and history of speculative Freemasonry. Some myths, however, have had no real posterity, but can still be found in some high grades, or in the symbolism of some rituals. Others borrow from the medieval imagination or from religious mysticism, and do not bother with historical truths to create legendary filiations with vanished guilds or orders.

The Old Charges is the name given to a collection of approximately one hundred and thirty documents written between the 14th and 18th centuries. Most of these documents were initially in manuscript form and later engraved or printed, all originating from England. These documents describe the duties and functioning of masons' and builders' guilds, as well as the mythical history of the craft's creation. It is within these fundamental texts, particularly the Regius poem (1390), also known as the Halliwell manuscript, and the Cooke manuscript (1410) for England, as well as the Schaw Statutes (1598) and the Edinburgh manuscript (1696) for Scotland, that speculative Freemasonry draws its sources. However, from a historical perspective, it does not claim a direct lineage with the operative lodges of that era.

The Standard Scottish Rite is a Masonic rite practiced primarily in Scotland. It is considered one of the oldest rites in Freemasonry, with origins dating back to the late 16th century. The rite is known for its rich history, symbolism, rituals, and focus on brotherly love.